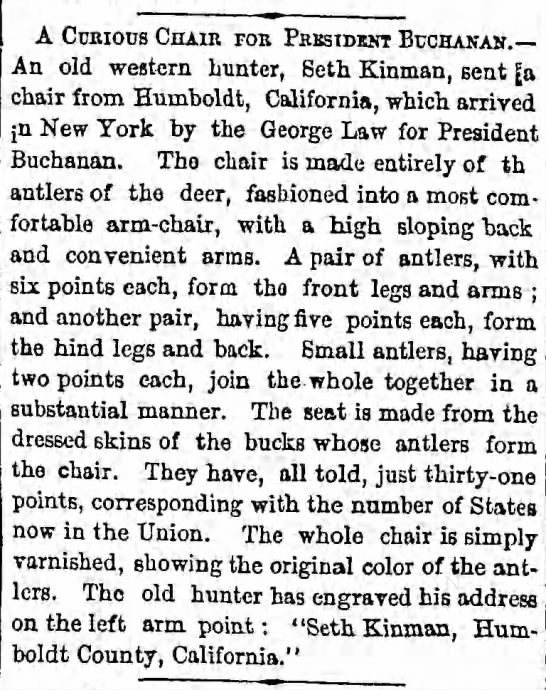

“‘For the first time I am writing for money; now I am frightened that some quick accident might happen.”

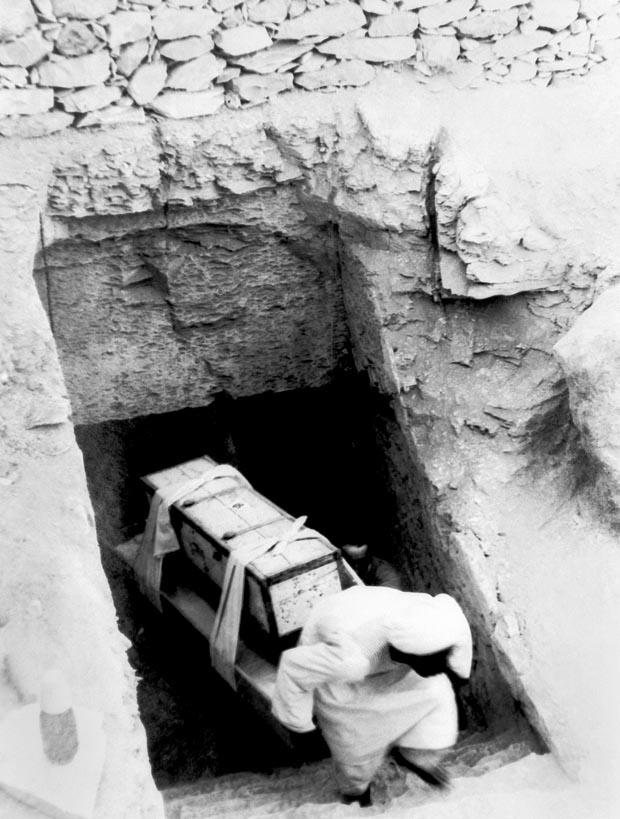

Isadora Duncan never did learn to drive. Out for a car ride in France with a friend and a chauffeur who promised to teach her to operate an automobile, the free-spirited dancer was done in by her free-flowing scarf, which entangled in one of the motor car’s front wheels and yanked her into the next world. It was the end of a short life that felt like a long one. An Associated Press article that appeared in the September 15, 1927 Brooklyn Daily Eagle on the morning after Duncan’s sudden death:

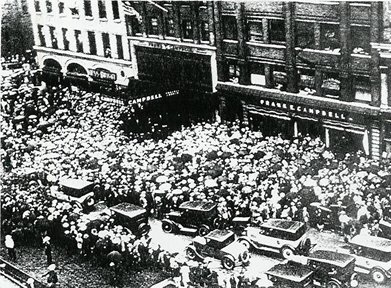

“Nice, France (AP)–The body of Isadora Duncan, dancer, whose adventurous career terminated in an automobile tragedy here last night, was locked in her studio today. Police are guarding the door and will permit no one to enter until a Soviet consular official has signed the necessary papers allowing friends to take charge of the body.

Miss Duncan left no will, according to Mrs. Mary Desto Perks, British newspaper woman who was driving with the dancer when she met death. Mrs. Perks said that all the dancer’s friends would testify that she intended all her property go to her blind brother, Augustin. Although Miss Duncan was recently financially embarrassed, Mrs. Perks declared the royalties on her book of memoirs were expected to net many thousands of dollars. The draperies and pictures in the studio here were alone valued at $10,000.

Citizenship in Doubt

At an autopsy performed today the verdict of accidental death due to strangulation was returned.

The only identifying document found in the Nice apartment was a Soviet passport, and police in accordance with French laws notified the nearest Russian Consul, who is at Marseilles. He was asked to come to Nice by motor at once.

A search at the American consulate here failed to show whether Miss Duncan had claimed American citizenship since 1921.

Miss Duncan was killed last night as she was learning to drive her new car.

A silken scarf of red–the color of which she was fond, and which seems to have symbolized her radicalism–fluttered about the neck of the dancer as she sped along the Promenade des Angels. With her was a French chauffeur, who was going to teach her to drive, and Mrs. Perks.

Killed Instantly

“The idea of ‘interpretive’ dancing came to her.”

The end of the long scarf whipped over the side of the car, became entangled in the front wheel and jerked the dancer from her seat. The chauffeur jammed on the brakes and he and Mrs. Perks disengaged the scarf from the limp body. The drove frantically to the St. Roch Hospital, but in vain. The doctors said her neck was broken and that death must have been instantaneous.

At one time a stage idol, Miss Duncan had long devoted herself to the training of young dancers. Her affairs did not appear to prosper, and her Neuilly studio had to be sold to pay her debts.

Had Premonitions of Death

Of late she had given much of her time to writing memoirs of her career, from which she hoped great things. She seems to have had premonitions of her death as, in talking with a correspondent of the Associated Press on Tuesday, she said:

‘For the first time I am writing for money; now I am frightened that some quick accident might happen.’

_______

From a hesitant debut as a 15-year-old girl in California, Isadora Duncan’s dancing feet carried her across two continents to wealth, a certain degree of fame and a life crowded with adventure and tragedy.

Bare Legs Stirred Protests

Born in San Francisco in May, 1878, the daughter of Charles Duncan, a dancing teacher, she received early training in the art on which she was to leave an indelible impress.

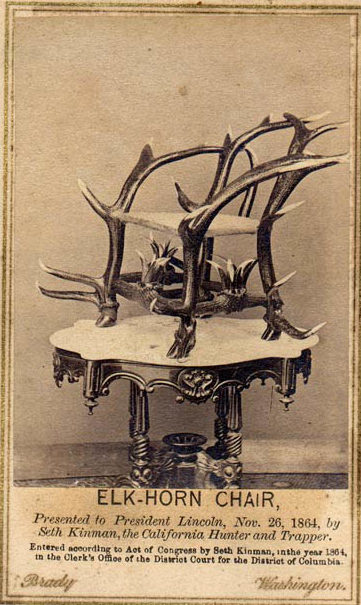

The idea of ‘interpretive’ dancing came to her and she began to devise dance figures of her own. In development of her idea she discarded customary costumes, appearing in filmy attire and with bare legs, a daring innovation in those days and one which brought many protests.

One of her first successes in New York was a dance version of ‘Omar Khayyam,’ in which she interpreted the spirit of the classic poem while the verses were recited by Justin Huntly McCarthy.

She was teaching a class of children in the Hotel Windsor, New York, when the fire broke out on March 7, 1899, which leveled the structure. She saved every one of the pupils at the risk of her life.

In the same year she decided to go to Europe and made the trip with her mother and brothers on a cattleboat, the venture being financed with the aid of friends. Europe was quick to recognize a form of art in her dramatic dancing, and she established a ‘Temple of Art’ in Paris.

King Edward VII, Gabriele d’Annunzio, Ernst Haeckel, Gordon Craig and Rodin the sculptor were listed among the admirers.

In 1904, her first financial success came when she started a school of classical dancing in Berlin, where she trained the girls who came to be known as the Duncan Dancers, forerunners of many later dancing groups of this character.

The girls performed, as their teacher did, in flowing draperies and bare feet.

Back in Paris again, in 1913, she encountered opposition from the authorities when she appeared as a nude bacchante, and in order to continue her fetes without interruption she purchased a villa at Neuilly, where she gave her brilliant parties for nearly four years.

Two Children Drowned

“There tragedy overtook her.”

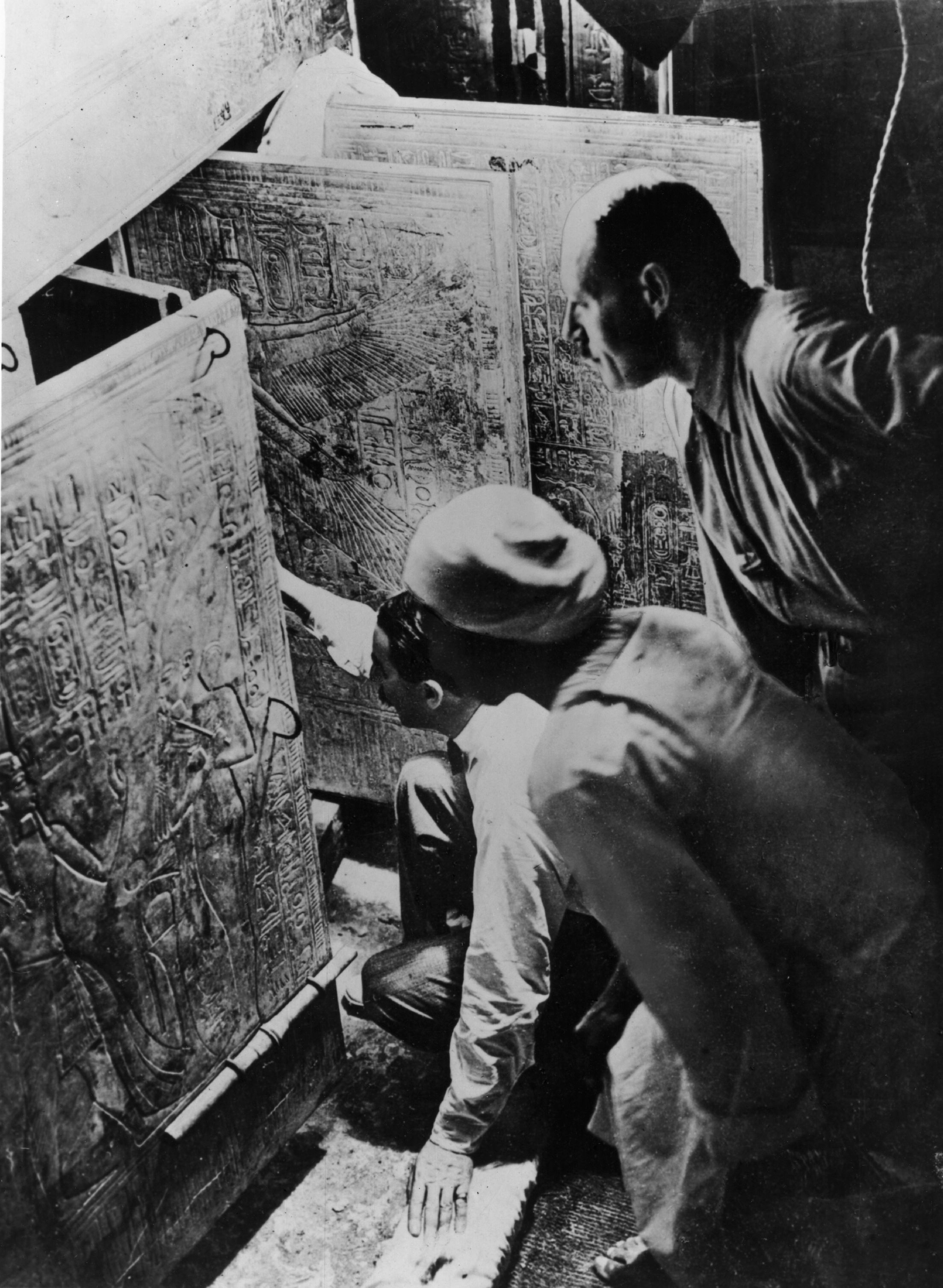

There tragedy overtook her. Her two children, Beatrice, 5, and Patrick, 2–she was never married and never revealed the name of their father–were drowned when the motorcar in which they were sitting plunged into the Seine River when it was cranked while in gear.

Of radical sympathies, her fortunes were adversely affected with the outbreak of the World War, and when the Russian revolution came in 1917 she immediately announced her adhesion to the Bolshevik cause. She went to Moscow some time later on the invitation of the Soviet Government to found a new school of dancing. Difficulties arose, and the plan was abandoned.

It was in Moscow that she married Sergei Yesenin, young Russian poet, in 1921. The next year she brought him to the United States and gave a series of dances. Later in Paris she announced that she had sent the young poet back to Russia, and eventually she divorced him, describing him as ‘really too impossible.’ He committed suicide in Russia in December, 1925.”

A man with a revolving head from Austria, a little woman who has fins instead of arms and two giants from Germany, a pair of midgets from Hungary, an English dwarf and a dog-faced man from Poland are the headliners of the collection of freaks that will start for America as soon as passport difficulties are cleared up.

A man with a revolving head from Austria, a little woman who has fins instead of arms and two giants from Germany, a pair of midgets from Hungary, an English dwarf and a dog-faced man from Poland are the headliners of the collection of freaks that will start for America as soon as passport difficulties are cleared up.