In 1923’s Our Hospitality, Buster Keaton travels via pedal-less dandy horse, the riding contraption mentioned in the post about early bicycles and walking machines. Doesn’t look ball-friendly, but Keaton had two kids.

Ideas and technology and politics and journalism and history and humor and some other stuff.

You are currently browsing the archive for the Film category.

In 1923’s Our Hospitality, Buster Keaton travels via pedal-less dandy horse, the riding contraption mentioned in the post about early bicycles and walking machines. Doesn’t look ball-friendly, but Keaton had two kids.

Paul Mazursky, the director of Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice, a 1969 film about a pre-Internet search for a social network at Big Sur and beyond, just passed away. He was a great teller of Hollywood tales, and a lot of institutional memory disappears with him. Here he talks about his greatest screen successes.

Tags: Paul Mazursky

Erich Segal was smart and successful, but he didn’t always mix the two. A Yale classics professor with a taste for Hollywood, he wrote Love Story, the novel and screenplay, and was met with runaway success in both mediums for his tale of young love doomed by cruel biology, despite the coffee-mug-ready writing and Boomer narcissism. (Or perhaps because of those blights.) While I don’t think it says anything good about us that every American generation seems to need its story of a pristine girl claimed by cancer–The Fault in Our Stars being the current one–the trope is amazingly resilient.

The opening of a 1970 Life article about Segal as he was nearing apotheosis in the popular culture:

“He looks almost too wispy to walk the 26 miles of the annual Boston Marathon, much less run all that way, even with a six-time Playboy fold-out waiting to greet him at the finish line. But Erich Segal doesn’t fool around. When he runs, he runs 26 miles (once a year, anyway–10 miles a day, other days), when he teaches classics he teaches at Yale (and gets top ratings from both colleagues and students), when he writes a novel he writes a best-seller. Love Story was published by Harper & Row in February and quickly hit the list. With his customary thoroughness Segal was ready: he had simultaneously written a screenplay of the story, and promptly sold it for $100,000. A bachelor (‘with intermittent qualms’), Segal has spent his 32 years juggling so many careers that it worries his friends. Even before Love Story he numbered among his accomplishments a scholarly translation of Plautus and part credit for the script of Yellow Submarine. At this rate, if his wind holds out, he may even win the Boston Marathon.

Love Story is Professor Segal’s first try at fiction, and when on publication day two months ago his editor at Harper & Row called up and said simply, ‘It broke,’ Segal remembers wondering whether he was talking about his neck or his sanity.”

Tags: Erich Segal

In 1990, during the mercifully short-lived Deborah Norville era of the Today Show, Michael Crichton stops by to discuss his just-published novel, Jurassic Park.

Tags: Deborah Norville, Michael Crichton

In this post, I used some 1971 photos of Anjelica Huston and Jack Nicholson playing LPs at his Mulholland Drive house, which were taken by the legendary Los Angeles photojournalist Julian Wasser, who is the Weegee of the West, sure, but also a thing all his own, ably adapting to shifting scenes, from street to crime to Hollywood. Wasser just published a book of his work, The Way We Were. Three more of his images follow.

From “Photo Ops,” Dana Goodyear’s excellent W piece:

Wasser’s first real camera was a Contax, which his father gave him when he was a junior in high school in the 1950s. He got himself a scanning radio and tuned in to the frequency used by the police. The first pictures he sold, while still a student at Sidwell Friends, a private Quaker school in Washington, D.C., were of crime scenes. “Crime’s exciting, and it sells,” he says. He got a gig at the Associated Press and met Arthur Fellig, the legendary photographer known as Weegee. “He came in plugging some film,” Wasser continues. “He was my hero.” From Weegee, he learned to use a Speed Graphic. “He was this real gruff, tough, down-to-earth guy, the epitome of a hard-nosed photographer, a street guy on the level of the cops he worked with. He used to beat them to the crime scene.”

That sensibility—an instinct for drama and the decisive moment, the dab of beauty with a smear of grit—put Wasser in the way of news. He was at the Ambassador Hotel the night Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated, and was with the crowd watching as Richard Ramirez, the infamous Night Stalker, was taken into custody by police. In 1969, three days after the actress Sharon Tate was murdered, Wasser, on assignment from Life, went to the crime scene on Cielo Drive with Tate’s husband, Roman Polanski, a pair of detectives, and a celebrity psychic searching for vibrational clues. (The Manson family hadn’t yet been named as suspects.) Wasser took a picture of Polanski, crouched and grim-faced beside a door smudged with fingerprint dust, where the word pig had been written in Tate’s blood. “I felt so bad for Polanski and for being there photographing it,” Wasser remembers. “He was just shattered.” The psychic, meanwhile, stole Wasser’s Polaroids and sold them to the tabs. Later, during the case brought against Polanski for having sex with a minor at Nicholson’s house on Mulholland, Wasser photographed the judge.•

Bernard Cornfeld, mutual-fund manager, and friends, 1974.

From Cornfield’s 1995 New York Times obituary by Diana B. Henriques:

Born in Istanbul in August 1927, Bernard Cornfeld was the son of a Romanian actor who moved his family to the United States in the early 1930’s. He graduated from Abraham Lincoln High School in Brooklyn and Brooklyn College. By 1954, he had become a mutual fund salesman, entering the industry just as mutual funds were experiencing their first strong surge of growth since the stock market crash of 1929.

In 1956, he moved to Paris, planning to sell shares of popular American mutual funds, chiefly the Dreyfus Fund, to Americans living abroad. Using his trademark recruiting challenge — “Do you sincerely want to be rich?” — he built Investors Overseas Services. At its peak, it was a far-flung organization that included a vast and intensely loyal sales force, a secretive Swiss bank, an insurance unit, real estate interests and a stable of offshore investment funds operating beyond the reach of any single country’s securities laws.

By 1970, his company had pumped millions of overseas dollars into the American mutual fund industry, initially through its aggressive sales force and then through Mr. Cornfeld’s trailblazing Fund of Funds, an offshore fund that invested in other mutual funds’ shares.

Mr. Cornfeld gave now-famous money managers like Fred Alger their start by selecting them to run funds owned by the Fund of Funds, which at its peak had more than $450 million invested in American mutual funds.

He also acquired enough financial power over American mutual funds and skirted close enough to the edges of Federal securities laws to attract the attention of the Securities and Exchange Commission, which in 1965 accused him and his company of violating American securities laws.

In 1967, the company settled the commission’s complaint by agreeing to wind up or sell all its American operations. The Fund of Funds also agreed to buy no more than 3 percent of any American mutual fund, the limit imposed by Federal mutual fund law.

After leaving the American market, Mr. Cornfeld continued to live lavishly, and his financial empire appeared strong until early 1970, when it suddenly disclosed that it was short of cash and had substantially overestimated its 1969 profits.•

The opening of “Super-Powered Love,” Lois Armstrong’s 1976 People article:

It would take a network in a ratings crisis to create a six million dollar man, with one telescopic-zoom eye and three nuclear-powered prosthetic limbs—the role Lee Majors plays so stoically on ABC every Sunday night. But, still mercifully, only God can make a Farrah Fawcett-Majors, as Lee’s offscreen wife calls herself. “She’s so gorgeous,” Majors glows, “she’s like a little girl. So cute, so beautiful inside, you wanna…” His natural reticence stifles further elaboration. The whole preposterousness of his series and its success (it shot from the Nielsen cellar last season to No. 5) may also have gotten to his brain and consciousness—which never were exactly “bionic.”

Farrah’s looks are indeed breath-stopping, and her own career is rocketing in commercials (Noxzema, Wella Balsam, Ultra-Brite); TV (as David Janssen’s girl next door on Harry O plus a starring part in a pilot); and film (playing with Michael York in the upcoming Logan’s Run). So, when queried about having children, Farrah replies, yes, but not for a couple of years, and Lee quips, “We already have bids from people who would like to have pick of the litter.”

In the meantime, Majors has begat, if nothing else, a spin-off series premiering Jan. 14 that he calls The Bionic Rip-Off—the official ABC title is The Bionic Woman. Lee’s dubiousness owes to the fear that the new show could dilute the Six Million Dollar Man ratings already perhaps in jeopardy. Part of Majors’ rise can be attributed to this fall’s plop from favor of his CBS competition, Cher, but she is almost certain to make at least a one-week Nielsen rebound next month among viewers curious to see the return of ex-husband Sonny, not to mention the TV premiere of her now gravid midriff. Lee may also begrudge the sweeter contract the bionic female, actress Lindsay Wagner, has chivied out of Universal. She, unlike Majors, negotiated a sizable share of any merchandising royalties—Six Million Dollar Man dolls were supposedly the hottest item in toy biz at Christmas, and he barely collected a pittance. Lindsay was also guaranteed five feature films—which could rankle Lee, because he blames his TV stereotyping for thwarting his own movie career.

Majors, 36, professes to be less threatened by his wife’s sudden stardom at 28—as long as it doesn’t interfere with her cooking his nightly supper.•

Tags: Dana Goodyear, Diana B. Henriques, Julian Wasser, Lois Armstrong, Robert F. Kennedy, Sharon Tate

Regardless of what actually killed him, Howard Hughes died of being Howard Hughes, eaten alive from the inside by neuroses. But that doesn’t mean he was alone at the feast. An autopsy suggested codeine and painkillers were among the culprits, and his personal physician, Dr. Wilbur Thain, whose brother-in-law Bill Gay was one of the executives angling for control of Hughes’ holdings, was treated like a precursor to Conrad Murray, though he was ultimately cleared of any wrongdoing.

From Dennis Breo’s 1979 People interview with Thain, who made the extremely dubious assertion that aspirin abuse claimed the man who was both disproportionately rich and poor:

Question:

Are you satisfied that Hughes received adequate medical attention?

Dr. Wilbur Thain:

Everything possible was done to help Hughes in his final hours. At no time did the authors of Empire try to get in touch with me. Yet they say in the book that an aviator friend of Hughes called me in Logan, Utah two days before Hughes’ death and told me, “I don’t want to play doctor, but your patient is dying.” I am quoted as telling the guy to mind his own business, since I had to go to a party in the Bahamas. Well, the first word I actually got that Hughes was in trouble was about 9 p.m. April 4, 1976—the night before he died. I was in Miami at the time—not Utah. At about midnight I was called and told that Hughes had suddenly become very critical. I was stunned. I left Miami at 3:30 a.m., arriving in Acapulco at 8 a.m. April 5.

Question:

What was the first thing you did?

Dr. Wilbur Thain:

Empire says the first thing I did was spend two hours shredding documents in Hughes’ rooftop suite at the Acapulco Princess. This is absolutely false. I walked straight into Hughes’ bedroom with my medical bag. He was unconscious and having multiple seizures. He looked like he was about to die. Other than one trip to the bathroom, I spent the next four hours with him.

Question:

Why did you then fly to Houston?

Dr. Wilbur Thain:

The Mexican physician who had seen Hughes advised against trying to take him to a local medical center, so we spent two hours trying to find an oxygen tank that didn’t leak and preparing the aircraft to fly us to Houston. We left at noon. He died en route.

Question:

Was Howard Hughes psychotic?

Dr. Wilbur Thain:

No, not at any time in his life. He was severely neurotic, yes. To be psychotic means to be out of touch with reality. Howard Hughes may have had some fanciful ideas, but he was not out of touch with reality. He was rational until the day he died.

Question:

Was Hughes an impossible patient?

Dr. Wilbur Thain:

That’s a masterpiece of understatement. He wanted doctors around, but he didn’t want to see them unless he had to. He would allow no X-rays—I never saw an X-ray of Hughes until after he died—no blood tests, no physical exams. He understood his situation and chose to live the way he lived. Rather than listen to a doctor, he would fall asleep or say he couldn’t hear.

Question:

Is that why you didn’t accept his job offer after you got out of medical school?

Dr. Wilbur Thain:

No, I just wanted to practice medicine on my own. I understand that Hughes was quite upset. I didn’t see him again for 21 years. He was 67 then. He had grown a beard, his hair was longer. He had some hearing loss partially due to his work around aircraft. That’s why he liked to use the telephone: It had an amplifier. He was very alert and well-informed. His toenails and fingernails were pretty long, but he had a case of onchyomycosis—a fungus disease of the nails which makes them thick and very sensitive. It hurt like hell to trim them. For whatever reason, he only sponge-bathed his body and hair.

Question:

What was the turning point?

Dr. Wilbur Thain:

After his successful hip surgery in August of 1973 he chose never to walk again. Once—only once—he walked from the bedroom to the bathroom with help. That was the beginning of the end for him. I told him we’d even get him a cute little physical therapist. He said, “No, Wilbur, I’m too old for that.”

Question:

Why did he decide not to walk?

Dr. Wilbur Thain:

I never had the chance to pry off the top of his head to see what motivated decisions like this. He would never get his teeth fixed, either. Worst damn mouth I ever saw. When they operated on his hip, the surgeons were afraid his teeth were so loose that one would fall into his lung and kill him!

Question:

What kinds of things did he talk about toward the end of his life?

Dr. Wilbur Thain:

The last year we would talk about the Hughes Institute medical projects and his earlier life. All the reporting on Hughes portrayed him as a robot. This man had real feelings. He talked one day about his parents, whom he loved very much, and his movies and his girls. He said he finally gave up stashing women around Hollywood because he got tired of having to talk to them. In our last conversation, he told me how much he still loved his ex-wife Jean Peters. But he was also always talking about things 10 years down the road. He was an optimist in that sense. If it hadn’t been for the kidney failure, Hughes might have lasted a lot longer.•

A 1976 Houston local news report on the death of Howard Hughes, whose demise was as shrouded in mystery as was much of his life.

Tags: Dennis Breo, Howard Hughes, Wilbur Thain

I don’t see why movies wouldn’t get universal releases on all platforms once smartphones and other distribution channels have saturated the globe, and I can see films being more fluid creations with numerous remixes, but Francis Ford Coppola goes even further when thinking about the future of the medium. From David Robb at Deadline Hollywood:

Francis Ford Coppola can see the future of cinema, and it’s going to be “live,” like a digital play or a virtual opera. Speaking before an overflow crowd at the closing of the Producer Guild‘s Produced By conference, Coppola said he sees a future in which movies will be presented “live” to audiences all around the world at the same time.

With the digital revolution, he said, “movies no longer have to be set in stone and can be composed and interpreted for different audiences that come to see it. Film has always been a recorded medium, but live cinema remixes might be ’30 percent pre-recorded as the actors do it live. You can do anything and you can do it live.”•

Tags: David Robb, Francis Ford Coppola

Joan Didion is one now, but when she was three her up-and-down marriage to fellow writer John Gregory Dunne was the topic of a 1976 People profile by John Riley. An excerpt:

Every morning Joan retreats to the Royal typewriter in her cluttered study, where she has finally finished her third novel, A Book of Common Prayer, due out early next year. John withdraws to his Olympia and his more fastidious office overlooking the ocean, where he’s most of the way through a novel called True Confessions. “At dinner she sits and talks about her book, and I talk about mine,” John says. “I think I’m her best editor, and I know she’s my best editor.”

While John played bachelor father to Quintana in Malibu, Joan spent a month in Sacramento—where she wrote the last 100 pages of the novel in her childhood bedroom in her parents’ home. She’s retreated there for the final month of all three novels. Her mother delivers breakfast at 9; her dad pours a drink at 6. The rest of the regimen: no one asks any questions about how she’s doing. Joan, a rare fifth-generation Californian, is the daughter of an Air Corps officer. She studied English at Berkeley and at 20 won a writing contest that led to an editing job with Vogue in New York. ‘All I could do during those days was talk long-distance to the boy I already knew I would never marry in the spring,’ she later wrote. John grew up in West Hartford, Conn., where his father was a surgeon. He prepped at a Catholic boarding school, Portsmouth Priory, and studied history at Princeton (where his classmates included Defense Secretary Don Rumsfeld and actor Wayne Rogers). After college he wrote for TIME.

He and Joan met in New York on opposite halves of a double date. When John’s girl passed out drunk in Didion’s apartment, she fixed him red beans and rice and, he recalls, “We talked all night.” Yet they remained only friends for six years until 1963, when they lunched to discuss the manuscript of her first novel, Run River. A year later they married.

California became home after Joan’s hypersensitivity pushed her to the brink of a crack-up in New York. ‘I cried in elevators and in taxis and in Chinese laundries,’ she recalls. “I could not work. I could not even get dinner with any degree of certainty.” Finally, in L.A., John and Joan began alternating columns in The Saturday Evening Post (they are presently sharing a his-and-hers column titled “The Coast” for Esquire). Soon they collaborated on their first filmscript, The Panic in Needle Park (which was co-produced by John’s brother Dominick). Her delicately wrought essays were collected in Slouching Towards Bethlehem, while John turned out nonfiction studies of the California grape workers’ strike (Delano) and 20th Century-Fox (The Studio).

They are only now emerging from two years of antisocial submersion in their novels. “This was the only time we’ve worked simultaneously on books,” John groans. “It was enormously difficult. There was no one to read the mail or serve as a pipeline to the outside world.” Finished ahead of John, Joan is baking bread, gardening and reestablishing contact with cronies like Gore Vidal and Katharine Ross. Unlike most serious writers, Joan and John have banked enough loot from the movies (they did script drafts for Such Good Friends and Play It As It Lays, among others) to indulge in two or three yearly trips to the Kahala Hilton in Hawaii. “Once you can accept the Hollywood mentality that says because you get $100,000 and the director gets $300,000, he’s three times smarter than you are, then it becomes a very amusing place to work,” John observes dryly. But, he adds: “If we didn’t have anything else, I think I’d slit my wrists.”

They’re currently dickering over two Hollywood projects, one about Alaska oil and another about California’s water-rights wars in the 1920s.•

Tags: Gore Vidal, Joan Didion, John Gregory Dunne, John Riley, Katharine Ross, Quintana Dunne

Here’s a rarity: Peter Benchley, author of Jaws, in a part of the preview featurette promoting the novel’s 1975 big-screen Spielberg adaptation, which changed so much about Hollywood filmmaking, pretty much creating the summer blockbuster season. The novelist interviews the director as well as producers Richard Zanuck and David Brown.

Tags: David Brown, Peter Benchley, Richard Zanuck, Steven Spielberg

Valerie Solanas was apparently never told that you don’t shoot the messenger. I was completely unaware until watching this video that she shot Andy Warhol the day before Sirhan Sirhan assassinated RFK. In the clip, Warhol and Candy Darling, who, it is written, came from out on the Island, preen for friends and media on a docked boat chartered by Jane Fonda. The line about Warhol’s Superstars “almost living” is striking. Isn’t that what we all dedicate a good portion of our lives to now, with our icons and our selfies and our reality stars? It’s great that everything is freer, but isn’t it surprising what we’ve done with the freedom, the endless channels? It’s life, yes, and it’s almost life.

Tags: Andy Warhol, Brigid Berlin, Brigid Polk, Candy Darling, Jane Fonda

Are we attracted to dystopic novels and films because they caution us or because they titillate us? Deep inside humans, along with an impulse to create, is one to destroy. Some get more joy from the seconds it takes to topple an elaborate sand castle than the hours it takes to build one. Perhaps these stories of decline and doom are psychological outlets for destructive tendencies, the way sports can be a safer outlet for aggression than war. Of course, sports has not ended war nor gave apocalyptic books and movies stopped us from trying to extinct ourselves.

Are we attracted to dystopic novels and films because they caution us or because they titillate us? Deep inside humans, along with an impulse to create, is one to destroy. Some get more joy from the seconds it takes to topple an elaborate sand castle than the hours it takes to build one. Perhaps these stories of decline and doom are psychological outlets for destructive tendencies, the way sports can be a safer outlet for aggression than war. Of course, sports has not ended war nor gave apocalyptic books and movies stopped us from trying to extinct ourselves.

Excerpts follow from two new pieces about dystopian art.

______________________________

From “Let’s Go to Dystopia,” by Diane Johnson at the New York Review of Books:

“Maybe there are people who read dystopian tales for self-improvement the way people used to read sermons, or for amusement—people who can edit out the very details that have most preoccupied the person who made them up, and read for the story alone. The stories, boiled down, are usually at bottom just the good old stories. Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange, set in London, is basically the same story as Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, set in the dystopian world of a mental institution; both Alex and McMurphy are forced into conformity and docility by institutional powers.

There are quest stories or love stories—a quest runs through Margaret Atwood’s trilogy about Crake and Oryx. Chang-rae Lee’s On Such a Full Sea is both a quest and a love story—a girl searches for her lover and for her brother, and so on. There’s no missing the appeal, especially for adolescents, of another common structure of these tales: a protagonist, often a teen, somehow preserved from the brainwashed docility of most people in his or her society—a rebel—solves some personal or social problem afflicting everyone (Hunger Games), and escapes from the future into what we recognize as a more normal world.

Utopias of course are just variations of dystopia, the reverse side of the same coin, in which a traveler from somewhere better tells about a distant society whose humanity and wisdom throw into relief the practices of our own, as in Sir Thomas More’s Utopia, or William Dean Howells’s A Traveler from Altruria, when the disingenuously leading questions that the suavely persuasive traveler asks his American host expose American laws, tastes, and manners as a kind of dystopia next to the traveler’s ideal Altruria. Through three hundred pages, America is indirectly portrayed as a dystopia of hypocrisy and self-delusion, the way Brobdingnagians, Yahoos, Lilliputians, and Houyhnhnms threw light on Swift’s and Gulliver’s England.”

______________________________

From “Why Hollywood Loves Dystopian Science Fiction,” by Alex Mayyasi at Priceonomics:

“Neal Stephenson knows a thing or two about science fiction. The author of thick, best-selling novels that cross genres but slant toward sci-fi, Stephenson also writes about technology and has worked part time on a private space company.

He is also tired of dystopian science fiction movies and video games. ‘A few weeks ago I think I actually groaned out loud when I was watching Oblivion and saw the wrecked Statue of Liberty sticking out of the ground,” he tells Morgan Warstler in an interview.

A proponent of the thesis that we have ‘lost our faith in technology to bring progress’ and ‘lost our ability to get important things done’ on an Apollo mission scale, Stephenson sees the ubiquity of dystopian visions as a cultural expression. Whereas it was once ‘refreshing, and extremely hip, to see depictions of futures that were not as clean and simple as Star Trek,’ we now experience ‘a strange state of affairs in which people are eager to vote with their dollars, pounds and Euros for the latest tech [like iPhones], but they flock to movies depicting a relentlessly depressing view of the future, and resist any tech deployed on a large scale, in a centralized way.’“

Tags: Alex Mayyasi, Diane Johnson

In a Guardian piece by Andrew Pulver about David Cronenberg, who’s at Cannes for the screening of his latest film, Maps to the Stars, the director asserts that the automobile deserves a place alongside the Pill in green-lighting the sexual revolution. And now that tablets and smartphones are more important than cars, what does that say about us? From Pulver’s article:

“Cronenberg was also quizzed on his fondness for sex scenes set in cars, with one journalist pointing out it went all the way back to his JG Ballard adaptation Crash. Cronenberg replied, not entirely seriously: ‘Crash was suppressed by Ted Turner [CEO of TBS, parent company of Crash’s US distributor Fine Line] because he said it would encourage them to have sex in cars. I said: there’s an entire generation of Americans who have been spawned in the back seats of 1954 Fords. I doubt I invented sex in cars. You have to remember, part of the sexual revolution came about because of the automobile, because young people could get away from their parents, and that was freedom. I don’t think I’m breaking any new territory.

‘I mean… why wouldn’t you? There are such great cars around.'”

_________________________

In 1979, David Cronenberg discusses casting porn star Marilyn Chambers:

Tags: Andrew Pulver, David Cronenberg

In 1978, Robbie Robertson and Martin Scorsese discuss the making of The Last Waltz, perhaps the best concert film ever. Little known fact: The movie’s cocaine wrangler was nominated for three Golden Globes.

Tags: Martin Scorsese, Robbie Robertson

How much did Orson Welles need a paycheck in 1979? Very much, apparently. That’s when he provided on-screen narration for the film version of evangelist Hal Lindsey’s cockamamie bestseller, The Late, Great Planet Earth, which prophesied the genius director’s continued ability to afford cognac, cigars and costly tickets to bullfights. Fucking unionized matadors! Well, it’s still fun in its own hokey way.

Tags: Hal Lindsey, Orson Welles

Rudolph Valentino wooed the world without a word. A gigantic star of the Silent Age–a pagan god, almost, especially to the ladies–Valentino’s early death at 31 led to one of the more raucous scenes imaginable at the public viewing in NYC of his body, a real day of the locusts that stretched into the night. The madness was captured in an article in the August 26, 1926 Brooklyn Daily Eagle.

__________________________

“Impressive scenes of funeral of famous film star”:

Heavyweight champ Jack Dempsey was one of the biggest things going in America in the Roaring Twenties, in an age when boxing was the king of sports. He was as big a star as Babe Ruth or Charlie Chaplin or Harry Houdini. Like all public figures of those days, Dempsey had a brand new audience to please: filmgoers, who could see his every imperfection in newsreels projected on larger-than-life screens. The boxer had added reason to be concerned about his punched-up mug: He wanted to make Hollywood movies. So during a three-year sabbatical from the ring, during which time he made more than ten silent shorts and starred in Manhattan Madness, Dempsey decided to get his nose fixed. From the August 10, 1924 Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

“Los Angeles–Whoever opposes Jack Dempsey in the next battle for the heavyweight ring championship will have an opportunity to test his marksmanship on a nice new nose.

The world’s champion has gone into retirement with a bandaged face after bowing to the filmdom fad of having one’s nose rebuilt to suit the cameraman.

Since Dempsey had been publicly connected with the motion picture industry all summer, there was no way out of it, and accordingly the plastic surgeon was given permission to cut away a piece of the boxer’s left ear and put it where it would make his nose look like Valentino’s.

It will be a week, the doctor said, before the new nose can be unveiled.”

Tags: Jack Dempsey

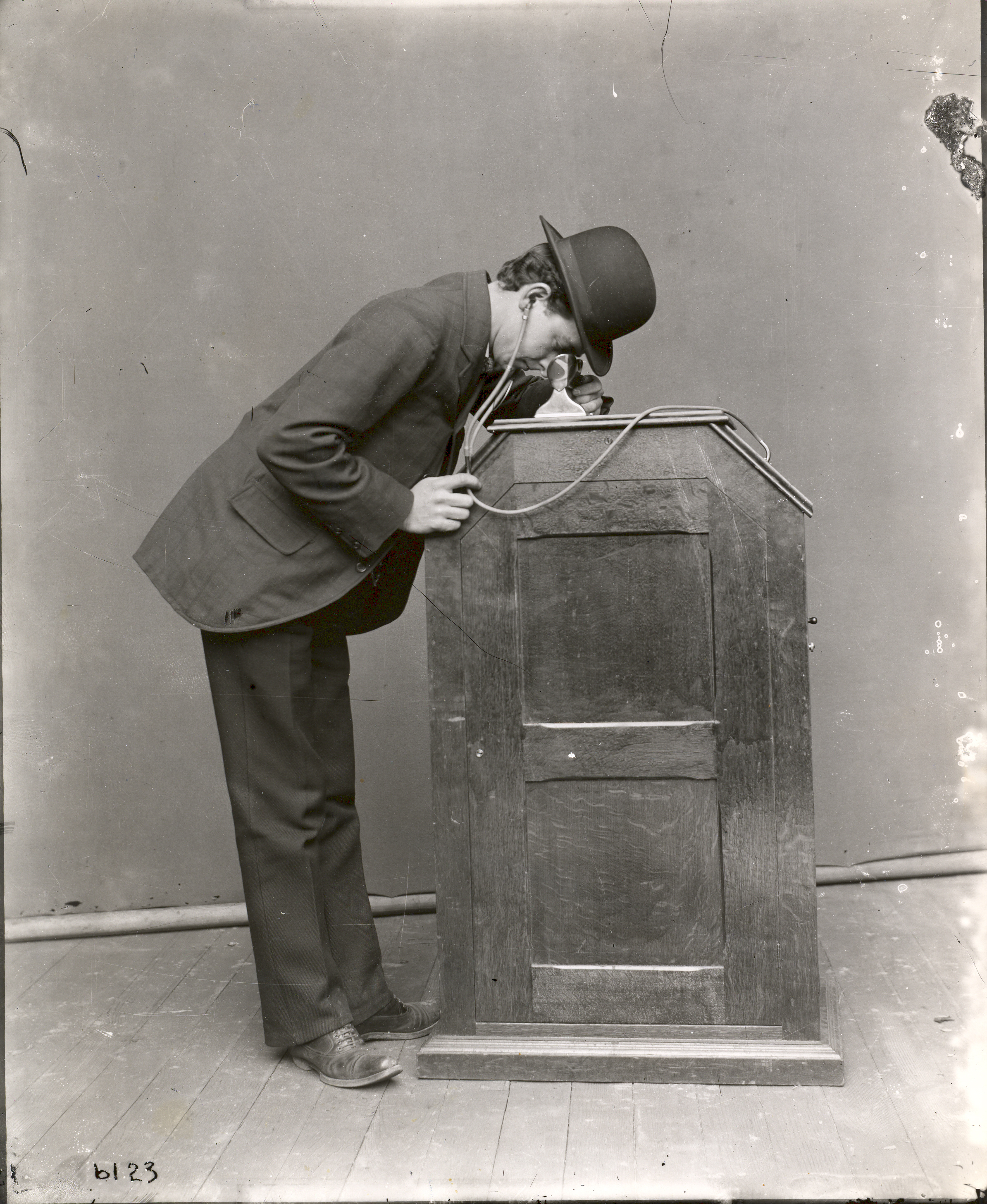

A non-projection version of the Kinetophone that presaged the theater type. It was referred to as a “peep show.”

One persistent problem for Thomas Edison was the development of the talking picture. He thought he had the answer in 1913, when he exhibited a projection version of his Kinetophone in New York City to much acclaim. But it was still just another phonograph record-based model that had to be synced to the images by an operator, Unfortunately, these employees generally had butterfingers, and the new sensation soon lost its lustre. Before the close of the following year, all the Kinetophone images and sound masters were destroyed in a warehouse fire. True talkies would have to wait. A New York Times article about the initial exhibition, which touched on the technical issues to come:

After Thomas A. Edison had invented the motion picture and the talking machine he dreamed of talking pictures, and the next morning he went to work again. For several years hints came from the Edison laboratory that the Kinetophone was in the process of development. Finally Edison spoke of his invention as a thing accomplished and yesterday, for the first time on any stage, the “Kinetophone” was on the bill at four of the Keith Theatres, the Colonial, the Alhambra, the Union Square, and the Fifth Avenue. To judge from the little gasps of astonishment and the chorus of “Ain’t that something wonderful?” that could be heard on all sides the Kinetophone is a success.

The problem involved was fairly simple. Mr. Edison was looking for perfect synchronization of record and film. The difficulty was to have a record sufficiently sensitive to receive the sounds from the lips of actors who would still be free to move about in front of the camera instead of being obliged to roar into the horn of a phonograph. But the difficulties have been overcome and the kinetoscope is actually in vaudeville and highly regarded there.

The first number of the exhibit was a descriptive lecture. The screen showed a man in one of those terribly stuffy, early eighties rooms that motion-picture folk seem to affect. He talked enthusiastically about the invention, and as his lips moved the words sounded from the big machine behind the screen. Gesture and speech made the thing startlingly real. He broke a plate, blew a whistle, dropped a weight. The sounds were perfect. Then he brought on a pianist, violinist, and soprano, and “The Last Rose of Summer” was never listened to with more fascinated attention. Finally the scope of kinetophone powers was further illustrated by a bugler’s apoplectic efforts, and the barking of some perfect collies.

The second number was a minstrel show with orchestra, soloists, end men, and interlocutor, large as life and quite as noisy. It brought down the respective houses but the real sensation of the day was scored quite unintentionally by the operator of the machine at the Union Square Theatre last evening. He inadvertently set the picture some ten or twelve seconds ahead of his sounds, and the result was amazing. The interlocutor, who, by a coincidence, wore a peculiarly defiant and offended expression, would rise pompously, his lips would move, he would bow and sit down. Then his speech would float out over the audience. It would be an announcement of the next song, and before it was all spoken the singer would be on his feet with his mouth expanded in fervent but soundless song.

This diverted the audience vastly, but the outbursts of laughter would come when the singer would close his lips, smile in a contented manner, bow, notes were still ringing clear. The audience, however, knew what happened, and the mishap did not serve to lessen their tribute of real wonder at Edison’s intent.•

Tags: Thomas Edison

Roman Polanski, genius and predator, was interviewed by Penthouse in 1974 at the time of Chinatown, which was my favorite film for many years. An excerpt:

“Question:

How did you come to make Chinatown, your newest film?

Roman Polanski:

Paramount acquired the rights to it and about a year ago Bob Evans, a vice-president at Paramount, called me and I came to Los Angeles and read the first draft. It had been written specifically for Jack Nicholson and I have always wanted to make a movie with him. So I decided I’d do it and I worked with Bob Towne for two months rewriting it. It was his original script. Already, at that stage, a picture of Faye Dunaway formed itself in my brain, and I was absolutely positive she was the only person who could play the role.

Question:

What was it like working with Jack Nicholson?

Roman Polanski:

Jack is the easiest person to work with that I have come across in my whole career. First of all, he’s tremendously professional, and secondly, it’s very easy for him to do anything you ask. I think he spoils the director, and the writer, because any lines you give him sound right even if they’re awkward or badly written. When he says something, it sounds authentic. He never asks you to change anything. Every other actor I’ve worked with has said, at some time, ‘Can I change this?’ or ‘Can I take this out?’ But that never happens with Jack. It’s amazing, really.

Question:

What about Faye Dunaway?

Roman Polanski:

With her it was just the opposite. I mean she’s hung-up. She’s the most difficult person I’ve worked with. She’s undisciplined, although she works hard. She prepares herself for ages – in fact, too much. She’s tremendously neurotic. Unflexible. She argues about motivations. She’s often late and so on. But then, when you see the final results, you tend to forget all the trouble you went through because she is very good indeed. It’s just a price you have to pay for it.

Question:

How did Jack and Faye get along?

Roman Polanski:

Oh, they get along very well. They’re great friends. So were Faye and I before we started the picture. And we are now. But throughout the production it was fire and water.

Question:

Does Chinatown represent a departure for you in either theme or treatment?

Roman Polanski:

Every film I make represents a departure for me. You see, it takes so long to make a film. By the time you get to the next one you’re already a different man. You’ve grown up by one or two years. Chinatown is a thriller and the story line is very important. There is a lot of dialogue. But I missed some opportunity for visual inventiveness. I felt sometimes as if I were doing some kind of TV show. I thought I had always been an able, inventive, creative director and there I was putting two people at a table and letting them talk. When I tried to make it look original I saw it start to become pretentious, so concentrated on the performances and kept an ordinary look.

Question:

Isn’t that better than having the audience acutely aware of the camera, like a thumb in their eye?

Roman Polanski:

Yes, but I don’t think that’s ever happened to me. Only when your camera makes them nauseous do the critics say, ‘His nervous camera moved relentlessly throughout the entire sequence’ and so on. I’ve read those criticisms of some pictures. It’s the same thing with writers. Sometimes a great stylist writes so smoothly that you’re not aware of what you’re swallowing.”

Tags: Faye Dunaway, Jack Nicholson, Robert Towne, Roman Polanski

Some actors pretend to be nervous during interviews, but John Belushi wasn’t kidding. In 1978, he sat uneasily, along with fellow actor Donald Sutherland and director John Landis, for a brief chat about Animal House, the film that was going to make him a huge star and put even more microphones in his face. Sutherland, conversely, could not give a fuck about this interview, a far healthier impulse.

Tags: Carolyn Jackson

As an exhibition of the amazing images by the late filmmaker Chris Marker opens at the Whitechapel Gallery, Sukhdev Sandhu of the Guardian has an article about these visions, simultaneously dreams and nightmares, which have profoundly influenced the culture, even this modest blog. An excerpt of William Gibson’s comments:

“I first saw ‘La Jetée’ in a film history course at the University of British Columbia, in the early 1970s. I imagine that I would have read about it earlier, in passing, in works about science fiction cinema, but I doubt I had much sense of what it might be. And indeed, nothing I had read or seen had prepared me for it. Or perhaps everything had, which is essentially the same thing.

I can’t remember another single work of art ever having had that immediate and powerful an impact, which of course makes the experience quite impossible to describe. As I experienced it, I think, it drove me, as RD Laing had it, out of my wretched mind. I left the lecture hall where it had been screened in an altered state, profoundly alone. I do know that I knew immediately that my sense of what science fiction could be had been permanently altered.

Part of what I find remarkable about this memory today was the temporally hermetic nature of the experience. I saw it, yet was effectively unable to see it again. It would be over a decade before I would happen to see it again, on television, its screening a rare event. Seeing a short foreign film, then, could be the equivalent of seeing a UFO, the experience surviving only as memory. The world of cultural artefacts was only atemporal in theory then, not yet literally and instantly atemporal. Carrying the memory of that screening’s intensity for a decade after has become a touchstone for me. What would have happened had I been able to rewind? Had been able to rent or otherwise access a copy? It was as though I had witnessed a Mystery, and I could only remember that when something finally moved – and I realised that I had been breathlessly watching a sequence of still images – I very nearly screamed.”

Tags: Chris Marker, Sukhdev Sandhu, William Gibson

Ridley Scott never really fully left the world of commercials when he started making features–his best work in the field was actually still ahead of him–but here he is in 1979 at the time of Alien‘s release discussing his branching out into full-length films. Footage is awful for the first few seconds.

Tags: Carolyn Jackson, Ridley Scott.

Peter Sellers being interviewed by talk show host/speed reader Steve Allen in 1964 about Dr. Strangelove, revealing how he used the voice for the titular character from the famed tabloid photographer Weegee. Mixed in are a couple of clips of the protean actor’s former employees recalling how he faked an injury to get out of doing the Major King Kong role.

Tags: Peter Sellers, Steve Allen, Weegee