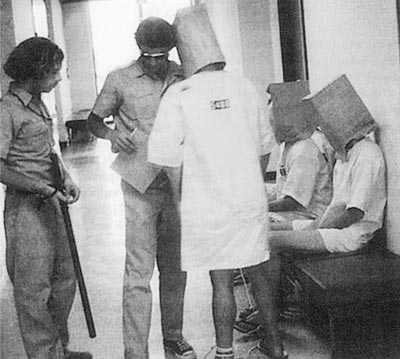

One revelation from the Reddit AMA conducted by Philip Zimbardo, still best known for the infamous 1971 Stanford Prison Experiment, a dress rehearsal more or less for Abu Ghraib, was that the psychologist was high school classmates with Stanley Milgram, author of the equally controversial “Obedience to Authority” study. That must have been some high school! Zimbardo was joined by writer Nikita Coulombe, to discuss their new book Man (Dis)connected. A few exchanges follow about the notorious test at Stanford.

___________________________

Question:

If you had a chance to do the Stanford Prison Experiment again, what would you do differently?

Philip Zimbardo:

Yes I would, I would have only played the role of researcher and there would be someone above me, who would be the superintendent of the prison and when things got out of hand I would have been in a better position to terminate the study earlier and more appropriately.

___________________________

Question:

In context of the famous prison experiment, when you were first organizing it, what were some of the specific dangers you tried to avoid?

Philip Zimbardo:

We selected young men who were physically healthy and psychologically normal, we had prior arrangements with student health if that was necessary. Each student was given informed consent, so they knew that there would likely be some levels of stress, so they had some sense of what was to come. Physical violence by the guards, especially if there was a revolt, solitary confinement beyond the established one hour limit, but primarily trying to minimise acts of sexual degradation.

___________________________

Question:

Being particularly interested in social psychology, I’m a big fan of what you have accomplished through your research. I was wondering what really got you interested in social psychology, and your research is connected to that of Stanley Milgram, another favourite psychologist of mine – so what I’m asking is what initially got you into this field of psychology, and what did you think of Milgram’s research when you first came across it?

permalink

Philip Zimbardo:

Thank you. I was interested in psychology from a young age: I grew up in the Bronx in the 1930s and started wondering why some people would go down certain paths, like joining a gang, while others didn’t. I was also high school classmates with Stanley Milgram; we were both asking the same questions.

___________________________

Question:

If there was a film adaptation dramatizing the events of the Stanford Prison Experiment, who would you want to play you?

Philip Zimbardo:

Glad you asked the question, amazingly there is a new Hollywood movie that just premiered at the Sundance film festival to great reviews winning lots of prizes titled The Stanford Prison Experiment. It will have national showings in America starting in July and hopefully in Europe in the Fall. I was hoping that the actor who would play me would be either Johnny Depp or Andy Garcia but they were not available so instead a wonderful young actor, Billy Crudup is Dr Z. You may be aware of his great acting in Almost Famous and Dr Manhattan in Watchmen.•

___________________________

“Jesus Christ, I’m burning up inside–don’t you know?”: