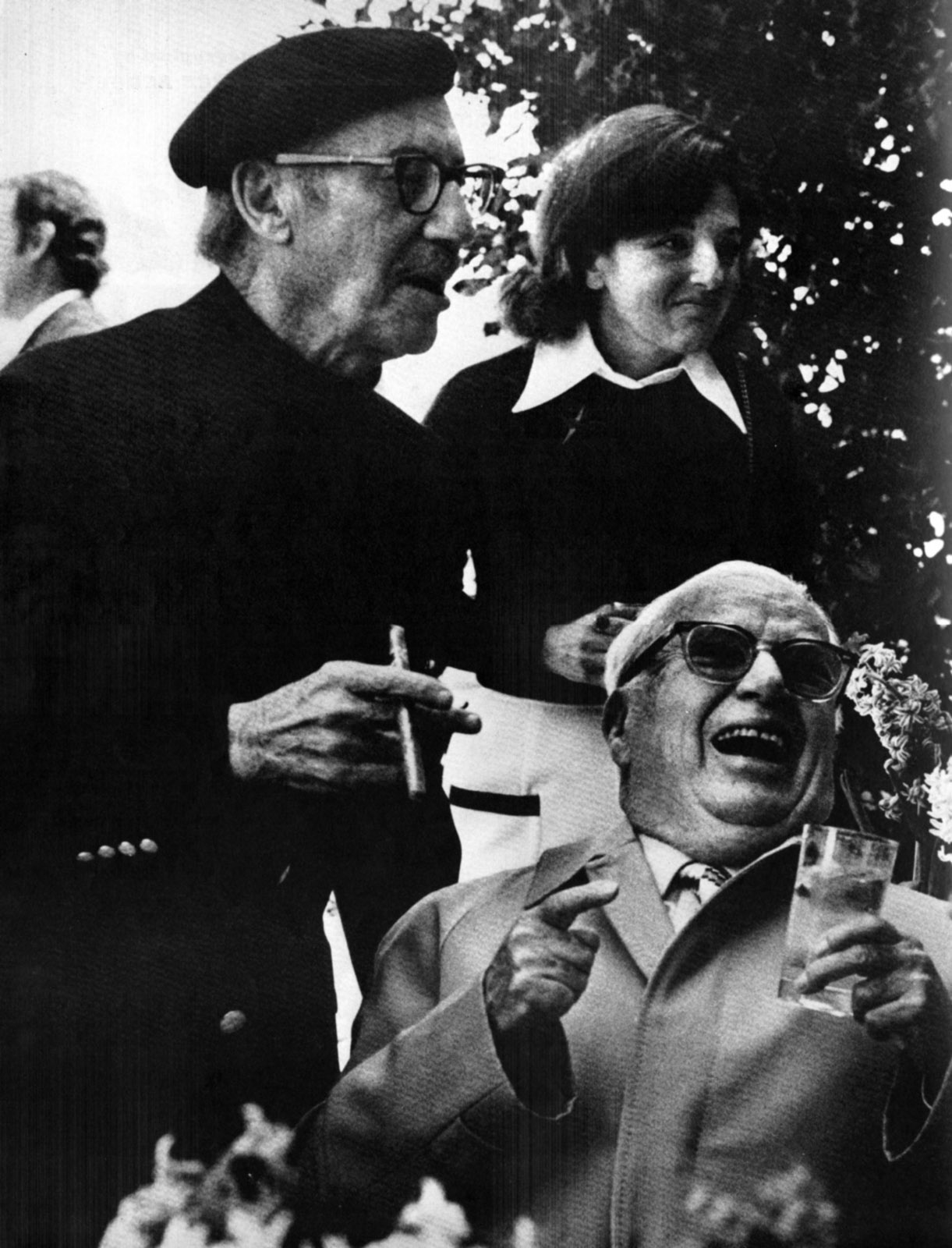

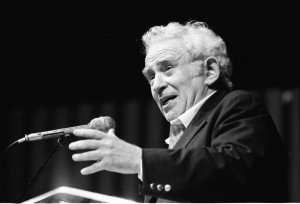

Kubrick photographed himself in the late 1940s with the help of a mirror, back when he was working for "Look" magazine.

I tend to divide people into two categories: Those who realize what an incredible genius Stanley Kubrick was, and other people I don’t like as much. The great website longform.org linked to Michael Herr’s excellent 1999 Vanity Fair piece (simply titled “Kubrick“) about his friend and collaborator, It was written right after the director’s death. Below are a few excerpts about Kubrick’s childhood and early career.

*****

Stanley hadn’t really been Bar Mitzvahed. He was barely making it in school; he couldn’t do junior-high English, let alone Hebrew, and besides, Dr. and Mrs. Kubrick weren’t very religious, and anyway, Stanley didn’t want to. He was not what anybody would have called well rounded. From the day he entered grade school in 1934, his attendance record had been a mysterious tissue of serial and sustained absences, his discipline nonexistent or at least nonapparent, his grades shocking. He’d received Unsatisfactory on “Works and Plays Well with Others,” “Respects Rights of Others,” and, inevitably, “Personality.” He did all right in physics, but he graduated from high school with a 70 average, and college was out of the question. At 17 he was already working as a freelance photographer for Look magazine, and he joined the staff, and he played a lot of chess, and read a lot of books, and otherwise arranged for his own higher education, as all smart people do.

*****

It’s fair only as far as it goes; just as he was multidisciplined, he was variously obsessive, and not fastidious about picking up information, and not afraid of whatever the information might be. Nobody who really thinks he’s smarter than everyone else could ask as many questions as he always did. He was beating the patzers in the park, working for Lookmagazine, sometimes using a series of still photos to tell a story, sometimes taking pictures of people like Dwight Eisenhower and George Grosz, Montgomery Clift, Frank Sinatra and Joe DiMaggio (and, I’m sure, keeping his eyes and ears open), reading 10 or 20 books a week, and trying to see every movie ever made. There was definitely such a thing as a bad movie, but there was no movie not worth seeing. As a kid he’d been part of the neighborhood multitude that poured ritually, communally, in and out of Loew’s Paradise and the RKO Fordham two or three times a week, and now he haunted the Museum of Modern Art and the few foreign-film revival houses, the very underground Cinema 16, and the triple-feature houses along 42nd Street.

*****

Reportedly he was already careless, even reckless, in his appearance, mixing his plaids in wild shirt, jacket and necktie combinations never seen on the street before, disreputable trousers, way-out accidental hairdos. He started infiltrating what- ever film facilities were in the city in those days, hanging around cutting rooms, labs, equipment stores, asking questions: How do you do that? and What would happen if you did this instead? and How much do you think it would cost if … ? He was jazz-mad, and went to the clubs, and a Yankees fan, so he went to the ball games too, all of this in New York in the late 40s and early 50s, a smart, spacey, wide-awake kid like that, it’s no wonder he was such a hipster, a 40s-bred, 50s-minted, tough-minded, existential, highly evolved classic hipster. His view and his temperament were much closer to Lenny Bruce’s than to any other director’s, and this was not merely a recurring aspect of his. He had lots of modes and aspects, but Stanley was a hipster all the time.

More Film posts: