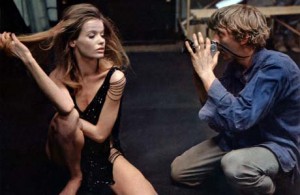

Michelangelo Antonioni’s drama about a fashion photographer who may or may not have accidentally recorded a murder being committed uses the alluring backdrop of Swinging ’60s London to meditate on the frustrating elusiveness of truth. Blow-Up became an art-house smash in the U.S. in 1966, which shouldn’t have been a surprise, perfectly attuned as it was to the Kennedy assassination paranoia that the Warren Commission was never able to quell.

David Hemmings plays an obnoxious, nameless photographer, who berates his female models and fancies himself something of an unappreciated artist. While in the park one day, he stealthily snaps a man and woman in the distance, but she eventually spies him and pursues him vigorously. The woman (Vanessa Redgrave) desperately wants him to turn over the film.

The photographer realizes why she’s so panicked when he later blows up the image and notices what might be a man in a bush pointing a pistol. Did the gunman commit a murder after the photo was taken? Or is he seeing something in the photo that isn’t really there? A friend peers at the enlarged picture and remarks to the photographer that it looks like one of “those paintings,” meaning an Op Art piece, whose meaning shifts depending on the perspective from which it’s viewed.

Early in the film, another of the photographer’s friends, an artist, opines about his Abstract paintings: “They don’t do anything at first…just a mess…afterwards I find something to hang onto…it adds up.” But what if life, more fleeting than art and too restless to truly study, does not? (Available from Netflix and other outlets.)

More Film Posts:

- Classic DVD: Invasion of the Bodysnatchers (1978).

- Classic DVD: The Stepford Wives. (1975)

- Classic DVD: Rollerball. (1975)

- New DVD: Exit Through the Gift Shop.

- Strange, Small & Forgotten Films: Stay Hungry. (1976)

- Classic DVD: Westworld. (1973)

- Classic DVD: Slacker. (1991)

- Strange, Small & Forgotten Films: Decasia: The State of Decay. (2002)

- Classic DVD: 32 Short Films About Glenn Gould. (1993)

- Classic DVD: Pickpocket. (1959)

- Strange, Small & Forgotten Films: Gates of Heaven. (1978)

- Classic DVD: Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore. (1974)

- Classic DVD: Playtime. (1967)

- Strange, Small & Forgotten Films: Last Night. (1998)

- Classic DVD: The Gleaners and I. (2000)

- Classic DVD: Sherman’s March. (1986)

- Strange, Small & Forgotten Films: The Bothersome Man. (2004)

- Classic DVD: Picnic at Hanging Rock. (1975)

- Classic DVD: Thieves Like Us. (1974)

- Classic DVD: Brief Encounter. (1945)

- Strange, Small & Forgotten Films: Police Beat. (2004)

- Classic DVD: The Killing. (1956)

- Strange, Small & Forgotten Films: Confessions of a Superhero. (2004)

- New DVD: The Exploding Girl.

- Strange, Small & Forgotten Films: Hi, Mom! (1970)

- Strange, Small & Forgotten Films: Targets. (1968)

- Classic DVD: Logan’s Run. (1976)

- Strange, Small & Forgotten Films: The Silent Partner. (1978)

- Classic DVD: Head. (1968)

- New DVD: Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans.

- Classic DVD: The Phantom of Liberty. (1974)

- New DVD: Big Man Japan.

- Strange, Small & Forgotten Films: All the Vermeers in New York. (1989)

- Classic DVD: The Other. (1972)

- Strange, Small & Forgotten Films: “La Soufriere.” (1976)

- Classic DVD: Network. (1976)