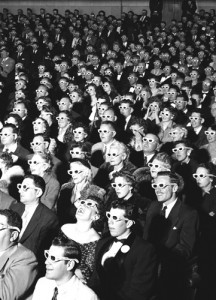

Michael Crichton’s prophetic 1978 genre picture foresaw an America with a small number of haves and many have-nots, and the ethical problems that could develop in a land of such disparate levels of wealth and so many emergent technologies. Adapted from a novel by Robin Cook, the Queens-born doctor who’s turned out a slew of medical thrillers, the film version of Coma was perhaps most famous in its day for its feminist hero, Dr. Susan Wheeler, played by Geneviève Bujold, but it now makes its mark most prominently in ways that cross gender lines.

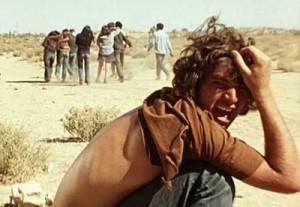

Boston Medical is a wealthy and prestigious hospital with a sterling reputation, as it seems no one has yet noticed that a higher-than-average number of young, healthy patients have signed in for mundane operations to remove appendixes or repair knees and have flatlined on the operating table. Dr. Wheeler certainly notices when her best friend is added to the growing list of the comatose, and she starts poking around the hospital for answers even though everyone, even her fellow doctor and boyfriend (Michael Douglas), believes she’s hysterical. As Wheeler follows the trail of corpses from the hospital to the nearby Jefferson Institute, a cutting edge facility where those healthy bodies with dead brains are kept pristine-but for what purpose?–she is sure that the “accidents” in O.R. are no mistake.

As Wheeler tries to sort through the welter of lies, she meets Jeffeson Institute attendant Mrs. Emerson (Elizabeth Ashley), who pointedly tells her, “I have no supervisor.” Emerson isn’t just talking about herself but about the ability of the powerful to prey on the weak in a society that clearly favors the former. There are certainly some hokey plot twists in Coma, as a few scenes were written to increase the action element at the expense of logic, but it’s still a powerful film instead of a dated one.

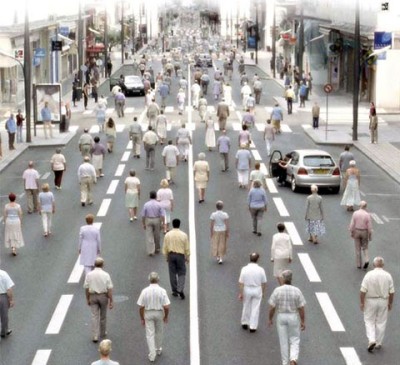

Bio-printers will be able to create perfect replacement organs in the future, so harvesting flesh, which actually still happens in developing countries, will eventually be a thing of the past. But does that mean our organs will be safe? Not exactly. What is ever more in play isn’t our organs themselves, but the information within one of them in particular–our brains. The nouveau tech corporations are aimed at locating and marking our personal preferences, tracking our interests and even our footsteps, knowing enough about what’s going on inside our heads to predict our next move. In a time of want and desperation and disparity of wealth, how much information will we surrender? It may be far less nefarious to read a mind than pluck a brain, but what we’re seeing now is probably just the beginning, as the profit motive is huge. To not pay attention to a line from Crichton’s film would mean we ourselves our in a collective coma: “We are dealing in an area of uncertainty, an area where there are no rules, contradictory laws and no clear social consensus as to what should be done.”•