Sorry to hear of the passing of Nora Ephron, who was one of the women who saved New Journalism in the ’60s and ’70s from being an all-boys school. From “Yossarian Is Alive and Well in the Mexican Desert,” her 1969 New York Times article about Mike Nichols filming Catch-22, a passage about the presence of Orson Welles and his legend:

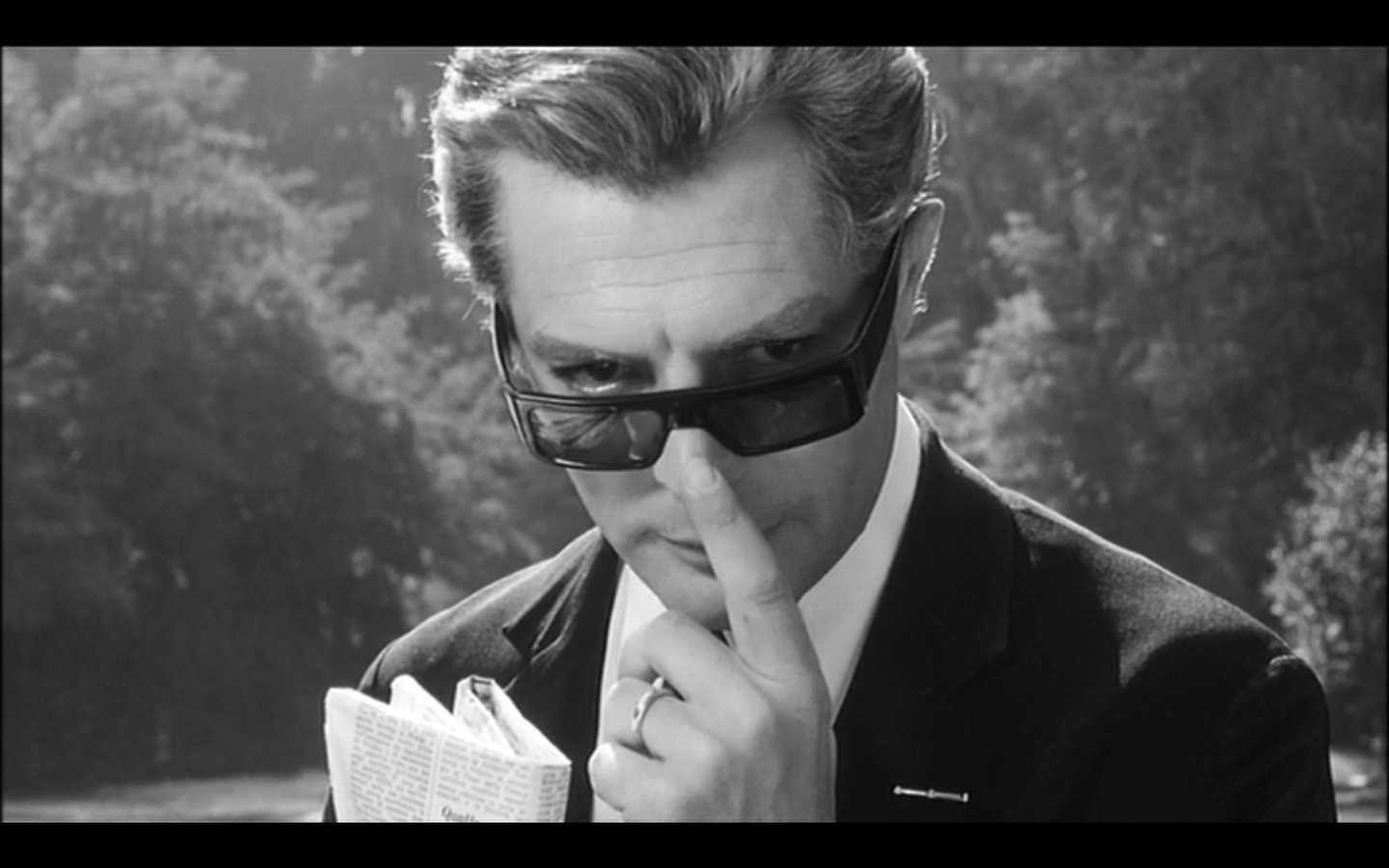

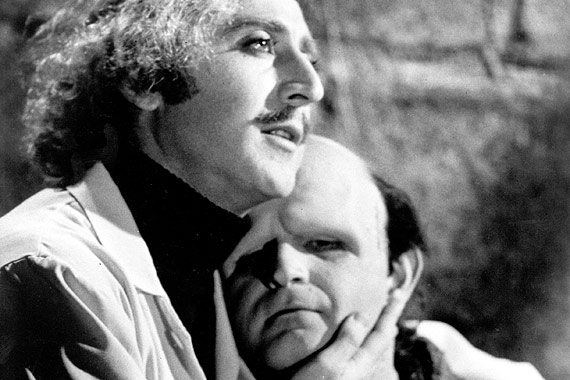

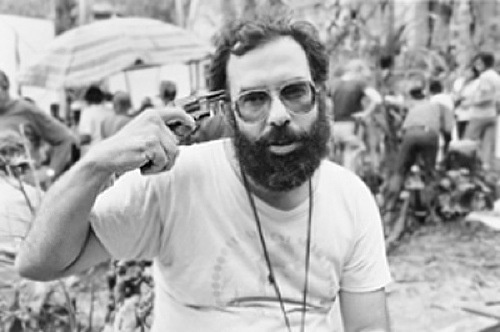

“The arrival of Orson Welles, for two weeks of shooting in February, was just the therapy the company needed: at the very least, it gave everyone something to talk about. The situation was almost melodramatically ironic: Welles, the great American director now unable to obtain big- money backing for his films, was being directed by 37-year-old Nichols; Welles, who had tried, unsuccessfully, to buy Catch-22 for himself in 1962, was appearing in it to pay for his new film, Dead Reckoning. The cast spent days preparing for his arrival. Touch of Evil was flown in and microscopically reviewed. Citizen Kane was discussed over dinner. Tony Perkins, who had appeared in Welles’s film, The Trial, was repeatedly asked What Orson Welles Was Really Like. Bob Balaban, a young actor who plays Orr in the film, laid plans to retrieve one of Welles’s cigar butts for an admiring friend. And Nichols began to combat his panic by imagining what it would be like to direct a man of Welles’s stature.

‘Before he came,’ said Nichols, ‘I had two fantasies. The first was that he would say his first line, and I would say, ‘NO, NO, NO, Orson !” He laughed. ‘Then I thought, perhaps not. The second was that he would arrive on the set and I would say, ‘Mr. Welles, now if you’d be so kind as to move over here. . .’ And he’d look at me and raise on eyebrow and say, ‘Over there?’ And I’d say, ‘What? Oh, uh, where do you think it should be?”

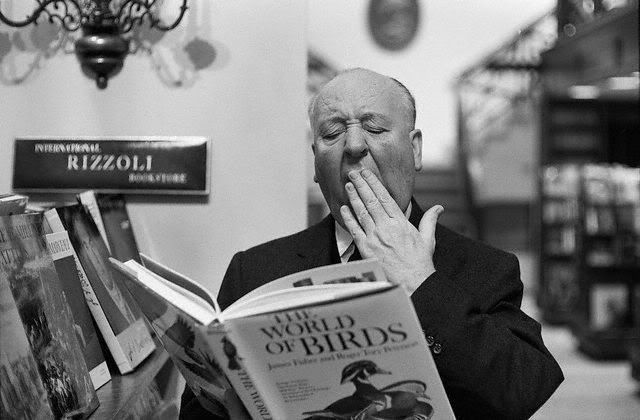

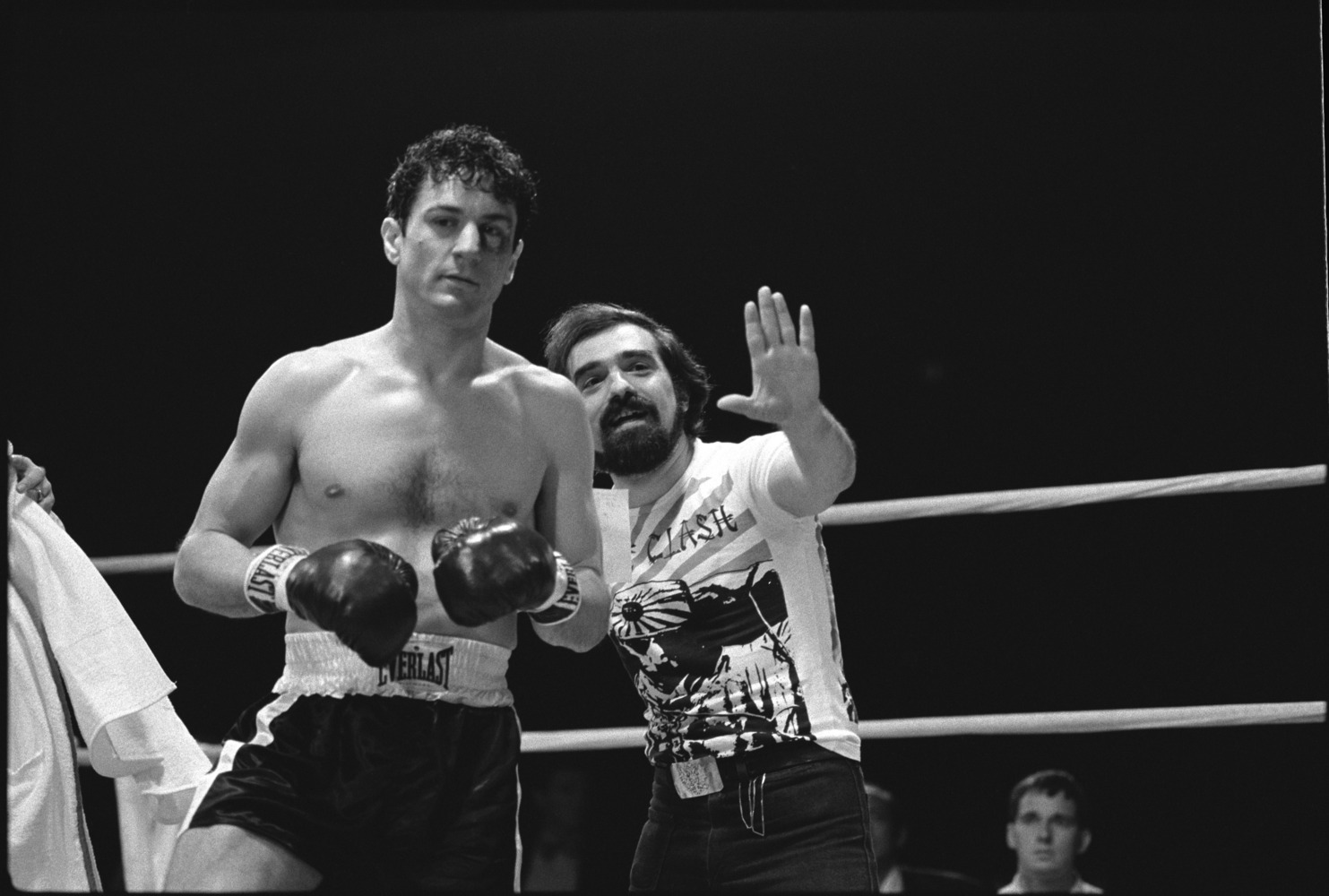

Welles landed in Guaymas with an entourage that included a cook and experimental film-maker Peter Bogdanovich, who was interviewing him for a Truffaut-Hitchcock-type memoir. For the eight days it took to shoot his two scenes, he dominated the set. He stood on the runway, his huge wet Havana cigar tilting just below his squinting eyes and sagging eye pouches, addressing Nichols and the assembled cast and crew. Day after day, he told fascinating stories of dubbing in Bavaria, looping in Italy and shooting in Yugoslavia. He also told Nichols how to direct the film, the crew how to move the camera, film editor Sam O’Steen how to cut a scene, and most of the actors how to deliver their lines. Welles even lectured Martin Balsam for three minutes on how to deliver the line, ‘Yes, sir.’

A few of the actors did not mind at all. Austin Pendleton got along with Welles simply by talking back to him.

‘Are you sure you wouldn’t like to say that line more slowly?’ Welles asked Pendleton one day.

‘Yes,’ Pendleton replied slowly. ‘I am sure.’

But after a few days of shooting, many of the other actors were barely concealing their hostility toward Welles–particularly because of his tendency to blow his lines during takes. By the last day of shooting, when Welles used his own procedure, a lengthy and painstaking one, to shoot a series of close-ups, most of the people on the set had tuned out on the big, booming raconteur.”