In order to promote The Monuments Men, which has received a coveted February release date, Bill Murray, a complicated man, just did an Ask Me Anything at Reddit. A few exchanges follow.

__________________________

Question:

If you could go back in time and have a conversation with one person, who would it be and why?

Bill Murray:

That’s a grand question, golly.

I kind of like scientists, in a funny way. Albert Einstein was a pretty cool guy. The thing about Einstein was that he was a theoretical physicist, so they were all theories. He was just a smart guy. I’m kind of interested in genetics though. I think I would have liked to have met Gregor Mendel.

Because he was a monk who just sort of figured this stuff out on his own. That’s a higher mind, that’s a mind that’s connected. They have a vision, and they just sort of see it because they are so connected intellectually and mechanically and spiritually, they can access a higher mind. Mendel was a guy so long ago that I don’t necessarily know very much about him, but I know that Einstein did his work in the mountains in Switzerland. I think the altitude had an effect on the way they spoke and thought.

But I would like to know about Mendel, because i remember going to the Philippines and thinking ‘this is like Mendel’s garden’ because it had been invaded by so many different countries over the years, and you could see the children shared the genetic traits of all their invaders over the years, and it made for this beautiful varietal garden.”

__________________________

Question:

Do you still talk to your deaf/mute assistant? If so, does he pretend like he can understand what you’re saying?

Bill Murray:

Well, we didn’t part well. I don’t communicate with her, she was a she. I was sort of ambitious thinking that I could hire someone that had the intelligence to do a job but didn’t have necessarily speech or couldn’t quite hear or spoke in sign language. She was a bright person and witty but she had never been away from her home before and even though I tried to accommodate more than I understood when I first hired her, she was very young in her emotional self and the emotional component of being away from her home was lacking. I tried my best, but I was working all day. She was lovely and very smart, but there’s a lot of frustration when you meet people who can’t speak well. Being completely disabled in that area causes a great amount of frustration, and this was going back 30 years or so before ether were the educational components that there are today. It didn’t go particularly well for me, but for a few weeks she really was a light and had a real spirit to her. She was like one of your own kids that never had a job, and then they get a job and realize that certain things are expected, and you can’t react to everything you don’t like or care about. So the first time you have a job and someone says ‘you have to do this’ – it was more complicated than she imagined. We were both optimistic, but it was harder than either of us expected to make it work.

__________________________

Bill Murray:

Someone asked “what movie was the most fun to act in” and deleted their comment, so here goes:

Well, I did a film with Jim Jarmusch called Broken Flowers, but I really enjoyed that movie. I enjoyed the script that he wrote. He asked me if I could do a movie, and I said ‘I gotta stay home, but if you make a movie that i could shoot within one hour of my house, I’ll do it.’

So he found those locations. And I did the movie.

And when it was done, I thought “this movie is so good, I thought I should stop.” I didn’t think I could do any better than Broken Flowers, it’s a film that is completely realized, and beautiful, and I thought I had done all I could do to it as an actor. And then 6-7 months later someone asked me to work again, so I worked again, but for a few months I thought I couldn’t do any better than that.

__________________________

Question:

What do you think of the current SNL cast?

Bill Murray:

They’re good. I don’t know them as well as I knew the previous one. But i really feel like the previous cast, that was the best group since the original group. They were my favorite group. Some really talented people that were all comedians of some kind or another. You think about Dana Carvey, Will, Hartman, all these wonderful funny guys. But the last group with Kristen Wiig and those characters, they were a bunch of actors and their stuff was just different. It’s all about the writing, the writing is such a challenge and you are trying to write backwards to fit 90 minutes between dress rehearsal and the airing. And sometimes the writers don’t get the whole thing figured out, it’s not like a play where you can rehearse it several times. So good actors – and those were really good actors, and there are some great actors in this current group as well I might add – they seem to be able to solve writing problems, improvisational actors, can solve them on their feet. They can solve it during the performance, and make a scene work. It’s not like we were improvising when we made the shows, but you could feel ways to make things better. And when you get into the third dimension, as opposed to the printed page, you can see ways to solve things and write things live that other sorts of professionals don’t necessarily have. And that’s why I like that previous group. So this group, there are definitely some actors in this group, I see them working in the same way and making scenes go. They really roll very nicely, they have great momentum, and it seems like they are calm in the moment.

__________________________

Question:

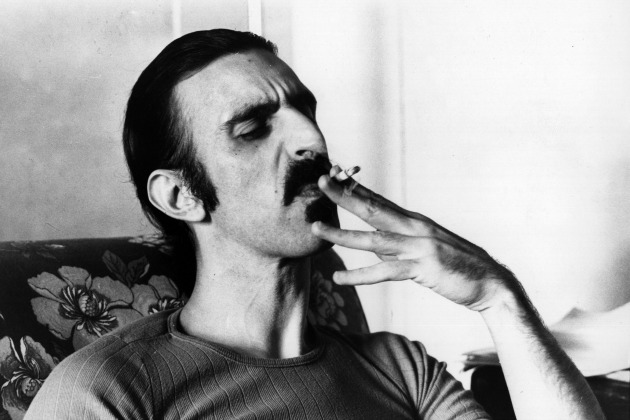

How do you feel about recreational marijuana?

Bill Murray:

Well that’s a large question, isn’t it? Because you’re talking about recreation, which everyone is in favor of. You are also talking about something that has been illegal for so many years, and marijuana is responsible for such a large part of the prison population, for the crime of self-medication. And it takes millions and billions of dollars by incarcerating people for this crime against oneself as best can be determined. People are realizing that the war on drugs is a failure, that the amount of money spent, you could have bought all the drugs with that much money rather than create this army of people and incarcerated people. I think the terror of marijuana was probably overstated. I don’t think people are really concerned about it the way they once were. Now that we have crack and crystal and whatnot, people don’t even think about marijuana anymore, it’s like someone watching too many videogames in comparison. The fact that states are passing laws allowing it means that its threat has been over-exaggerated. Psychologists recommend smoking marijuana rather than drinking if you are in a stressful situation. These are ancient remedies, alcohol and smoking, and they only started passing laws against them 100 years ago.

__________________________

Question:

What was the oddest experience you had in Japan?

Bill Murray:

The oddest… well, I was eating at a sushi bar. I would go to sushi bars with a book I had called “Making out in Japanese.” it was a small paperback book, with questions like “can we get into the back seal?” “do your parents know about me?” “do you have a curfew?”

And I would say to the sushi chef ‘Do you have a curfew? Do your parents know about us? And can we get into the back seat?’

And I would always have a lot of fun with that, but that one particular day, he said “would you like some fresh eel?” and I said “yes I would.” so he came back with a fresh eel, a live eel, and then he walked back behind a screen and came back in 10 seconds with a no-longer-alive eel. It was the freshest thing I had ever eaten in my life. It was such a funny moment to see something that was alive that no longer was alive, that was my food, in 30 seconds.•