Hopefully Stephen Galloway of the Hollywood Reporter will now be able to sleep easily knowing Harvey Weinstein and his ilk are able to afford David Boies, former Mossad officers and numerous international security agencies when trying to undermine, cajole and intimidate victims and journalists determined to go public about sexual harassment and abuse. Ronan Farrow’s latest New Yorker bombshell, “Harvey Weinstein’s Army of Spies,” investigates the stealthy and labyrinthine operation Weinstein bankrolled while trying to keep his house of cards from toppling off the table. It’s as mind-blowing as the actual accusations, this story of a cabal of spies and A-list legal minds retained to do the dirty work. An excerpt:

In the fall of 2016, Harvey Weinstein set out to suppress allegations that he had sexually harassed or assaulted numerous women. He began to hire private security agencies to collect information on the women and the journalists trying to expose the allegations. According to dozens of pages of documents, and seven people directly involved in the effort, the firms that Weinstein hired included Kroll, one of the world’s largest corporate intelligence companies, and Black Cube, an enterprise run largely by former officers of Mossad and other Israeli intelligence agencies. Black Cube, which has branches in Tel Aviv, London, and Paris, offers its clients the skills of operatives “highly experienced and trained in Israel’s elite military and governmental intelligence units,” according to its literature.

Two private investigators from Black Cube, using false identities, met with the actress Rose McGowan, who eventually publicly accused Weinstein of rape, to extract information from her. One of the investigators pretended to be a women’s-rights advocate and secretly recorded at least four meetings with McGowan. The same operative, using a different false identity and implying that she had an allegation against Weinstein, met twice with a journalist to find out which women were talking to the press. In other cases, journalists directed by Weinstein or the private investigators interviewed women and reported back the details.

The explicit goal of the investigations, laid out in one contract with Black Cube, signed in July, was to stop the publication of the abuse allegations against Weinstein that eventually emerged in the New York Times and The New Yorker. Over the course of a year, Weinstein had the agencies “target,” or collect information on, dozens of individuals, and compile psychological profiles that sometimes focussed on their personal or sexual histories. Weinstein monitored the progress of the investigations personally. He also enlisted former employees from his film enterprises to join in the effort, collecting names and placing calls that, according to some sources who received them, felt intimidating.

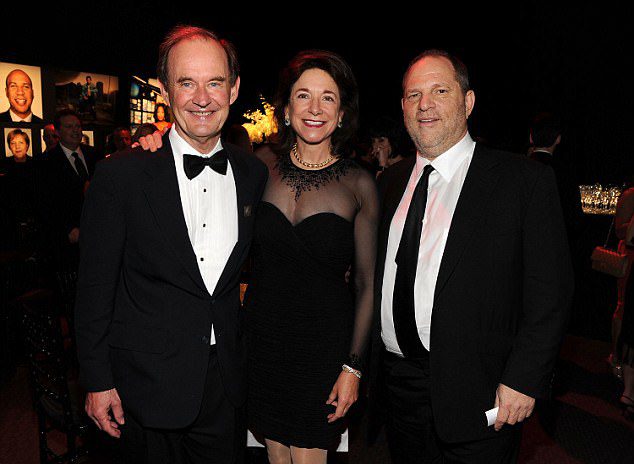

In some cases, the investigative effort was run through Weinstein’s lawyers, including David Boies, a celebrated attorney who represented Al Gore in the 2000 Presidential-election dispute and argued for marriage equality before the U.S. Supreme Court. Boies personally signed the contract directing Black Cube to attempt to uncover information that would stop the publication of a Times story about Weinstein’s abuses, while his firm was also representing the Times, including in a libel case.

Boies confirmed that his firm contracted with and paid two of the agencies and that investigators from one of them sent him reports, which were then passed on to Weinstein. He said that he did not select the firms or direct the investigators’ work. He also denied that the work regarding the Times story represented a conflict of interest. Boies said that his firm’s involvement with the investigators was a mistake. “We should not have been contracting with and paying investigators that we did not select and direct,” he told me. “At the time, it seemed a reasonable accommodation for a client, but it was not thought through, and that was my mistake. It was a mistake at the time.”•