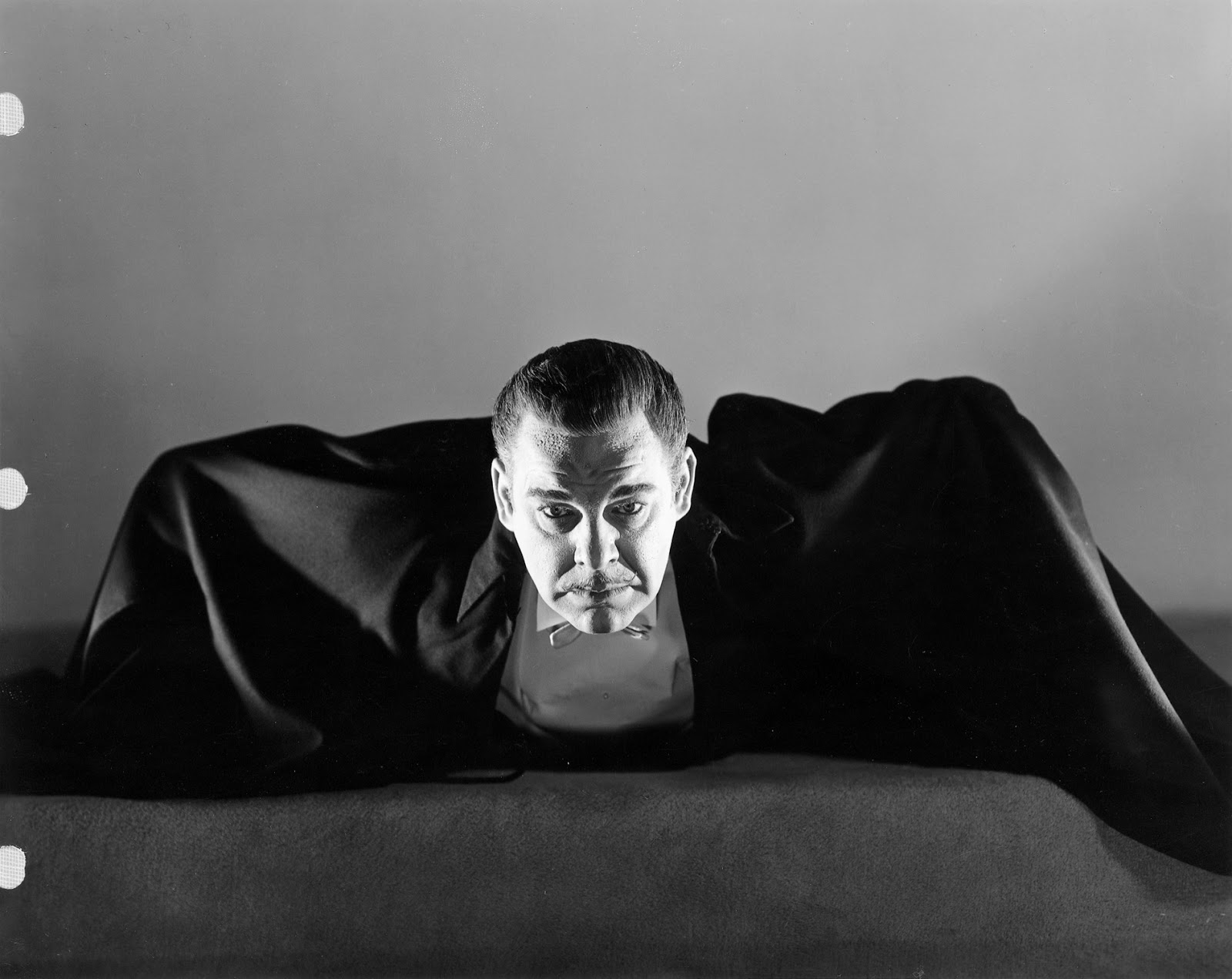

Truly understanding the consciousness of a human being let alone a different species is impossible for us. Someday, though not soon, we’ll likely be able to map the brains of beasts (including us) and upload them into computers. Then perhaps an unparalleled sense of empathy will be possible (though it will bring along with it all sorts of complications). Currently, AI is as inept as Homo sapiens in making this magic happen.

Excerpts from: 1) Elizabeth Kolbert’s NYRB piece “He Tried to Be a Badger,” which looks at the lack of human understanding of our fellow creatures, and 2) Alan Smeaton’s Irish Times article, “Artificial Intelligence Is Dead,” which focuses on the limitations of machines achieving and perceiving consciousness.

From Kolbert:

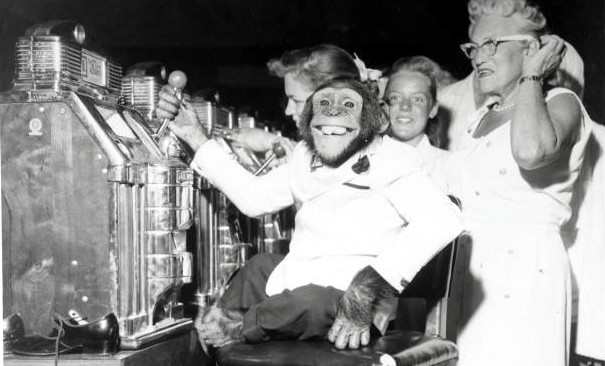

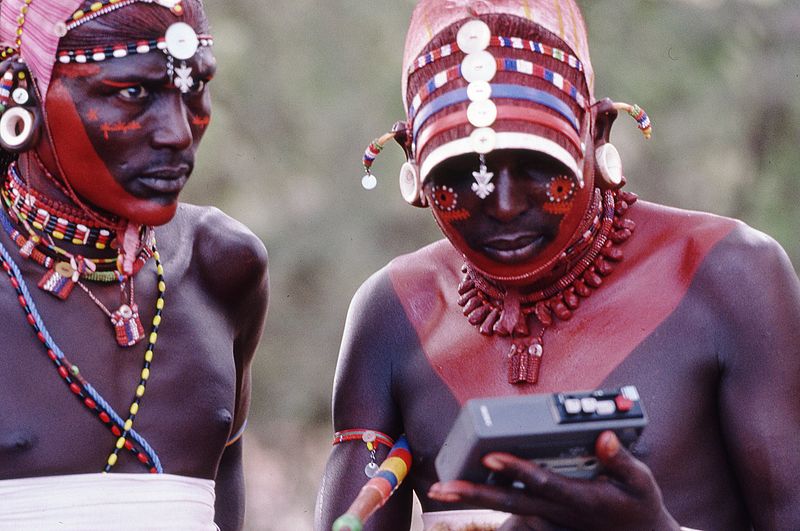

In his classic essay “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” the philosopher Thomas Nagel attempts to enter the pteropine mind. Bats, he notes, spend a lot of their time dangling upside down. At night, they swoop around, searching for bugs and issuing high-pitched chirps that allow them to navigate in the dark. A person can imagine what it’s like to hang by his toes from a rafter. He may also be able to envisage having webbed arms, and maneuvering via echolocation, and catching insects on the fly. From this, he can get a sense of what it would be like for him to behave like a bat. But still he would not know what it’s like tobe a bat. Even in his wildest dreams, a person has access only to the resources of the human mind, and here, according to Nagel, lies the rub: “Those resources are inadequate to the task.”

Nagel’s essay first appeared in 1974, in the journal The Philosophical Review. It could just as well have been titled “What Is It Like to Be an Aardvark?” or “What Is It Like to Be a Zebra?” The gap separating humans from bats is much the same as—or at least of a similar magnitude to—that which separates us from sloths and pangolins and manatees and meerkats. Like us, these animals are mammals, and we concede that they are capable of some sort of subjective experience. (“Too far down the phylogenetic tree,” Nagel observes, and “people gradually shed their faith that there is experience there at all.”)

Though Nagel wasn’t much interested in other species—his real subject was the irreducibility of consciousness—to those who were, his question became a kind of taunt, an elbow thrust across academic disciplines.•

From Smeaton:

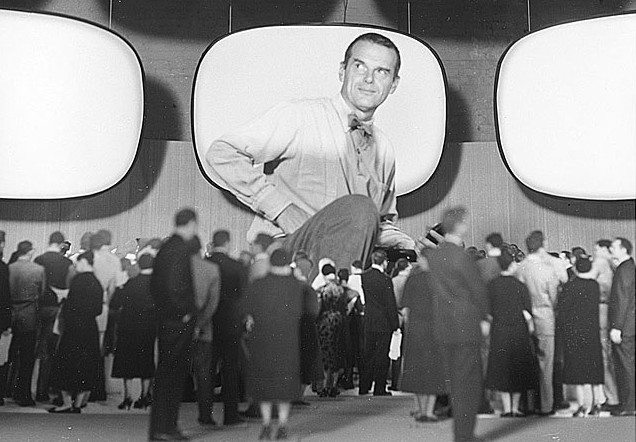

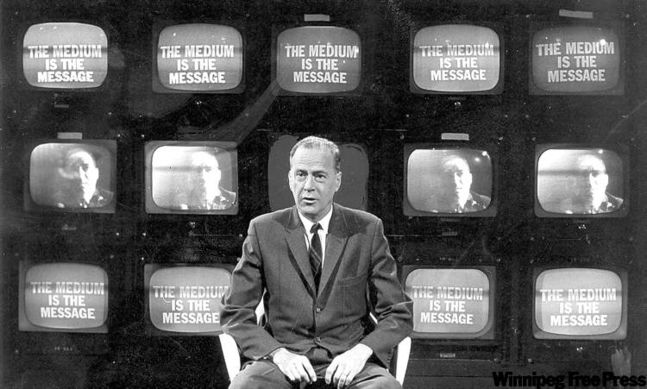

Automatic recognition of image and video content is now much more than just recognising faces in pictures: it now assigns captions or tags to describe what is in the picture. Facebook uses this to make images accessible to the blind and Google Photos use it to tag personal photos.

IBM’s Watson system can read in text documents and answer questions about their content. Watson was fed the entire contents of Wikipedia and competed in the US game show Jeopardy against two previous champions. Watson won.

Jeopardy is like a cross between University Challenge and Only Connect, requiring extensive real world knowledge, and clever analysis of language. Watson is now being applied by IBM to medicine and scientific literature to help users understand the huge volume of scientific information being produced daily.

Think also of self-driving cars, soon to be navigating our roads, avoiding obstacles, including each other, in order to take us safely and economically to our destinations.

These examples, and many others, are all being touted as forms of AI.

But are they AI? Well, no actually. Companies like calling their technologies AI. It sounds better, it’s more futuristic, but it’s not AI: it’s actually data analytics.

IBM’s Watson, for example, achieves what it does by analysing sentences to draw connections across sentences, paragraphs, documents. What makes it clever is that it does this for really complex text, and it does it at enormous scale, processing vast amounts of data.

It is not reading and understanding in the way we envisaged an AI machine would.•