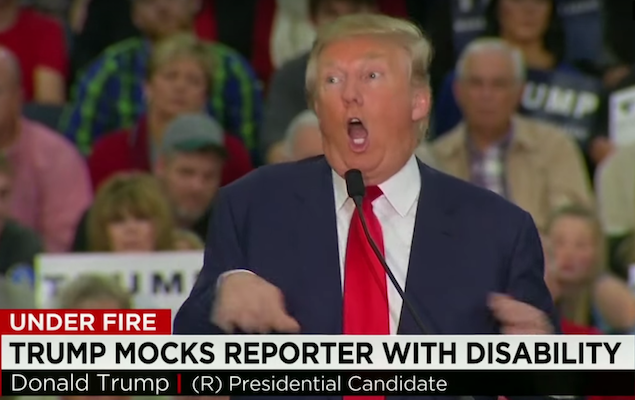

Somewhere prominent in the annals of great insults is “short-fingered vulgarian,” an enduring epithet repeatedly spit in the face of the hideous hotelier Donald Trump from the wonderfully poisonous pages of Spy. The aggrieved party wiped the saliva from his cheek with his wee baby hands, but he couldn’t forgive or forget this taunt for all times.

The description may not possess the extreme brevity of the Beckett curse “critic” or the Reagan Era diminution of “liberal,” but it’s a gift that keeps on giving, long after the end of the Graydon Carter and Kurt Andersen publication or the heyday of the Magazine Age itself. The lacerating line reemerged in major way earlier this year when a variant of it was employed by Presidential aspirant Marco Rubio, a rare moment of momentum for the Little Marco that couldn’t.

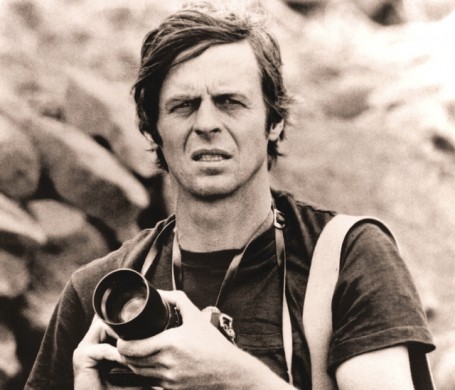

The slight had its genesis in a 1983 GQ feature about the orange supremacist penned by Carter. It was then a simple observation which surprisingly began a war of words between the men, and though the editor was pretty much forced occasionally to accept the status of bemused frenemy, most of the time Trump wanted to wrap his hands around the journalist’s neck, if only it were anatomically possible.

In an excellent Vanity Fair “Hive” piece, Carter analyzes this Baba Booey of a campaign season, while revealing that an unintended consequence of the profile he penned 33 years ago may have been that it abetted the political ascent of Bull Connor as a condo salesman. The opening:

In 1987, Michael Kelly, later a celebrated editor but at the time a reporter for The Baltimore Sun, took Fawn Hall, a secretary to Oliver North, as his guest to the White House Correspondents’ Association dinner. Hall had been caught up in the whole Iran-contra scandal, and her arrival shocked the swells of Washington, who were used to seeing business, political, sports, and movie grandees on the arms of major news organizations. Thus began a tradition of media companies prowling the nether regions of their coverage to come up with the tabloid oddity of the moment for their novelty guest.

Novelty guests don’t know they’re novelty guests. They just think they’re guests. That evening in May 1993, Vanity Fair had two tables and we filled them with the likes of Christopher Hitchens, Bob Shrum, Barry Diller and Diane von Furstenberg, Peggy Noonan, Tipper Gore, and Vendela Kirsebom, a Swedish model who professionally went by her first name and who was then at or near the top of the catwalk heap. I sat Trump beside Vendela, thinking that she would get a kick out of him. This was not the case. After 45 minutes she came over to my table, almost in tears, and pleaded with me to move her. It seems that Trump had spent his entire time with her assaying the “tits” and legs of the other female guests and asking how they measured up to those of other women, including his wife. “He is,” she told me, in words that seemed familiar, “the most vulgar man I have ever met.”

The next time I saw Trump in that giant ballroom of the Washington Hilton was in 2011. This time he had come as the guest of Washington Post heiress Lally Weymouth. It was at the beginning of Trump’s lunatic “birther” rampage, and he was probably quite pleased with himself at being in the midst of all this sequined ersatz Washington glamour. Much as Trump loves to be the center of attention, the attention he got that night didn’t go according to plan. First, President Obama ridiculed him mercilessly from the dais. The fact that the president’s birther tormentor was in the room appeared to give him a lift—he was seriously funny and his timing was flawless. Then the evening’s headliner, Seth Meyers, stood up and really went to town on Trump. Weymouth’s table was right beside us, so I got a ringside view of the poor fellow as he just sat there, stony-faced and steaming—and of course unaware, like everyone else, that while Obama was launching his jokes he was also launching the attack that would kill Osama bin Laden. To think that next spring Trump could be attending the White House Correspondents’ Association dinner as the commander in chief renders one almost speechless.

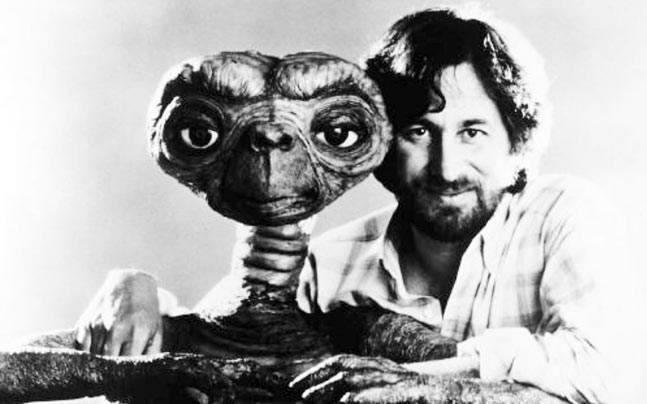

My relationship with Trump, if you could call it a relationship, goes back more than three decades. I first met him in 1983, when I was reporting a story I was doing on him for GQ magazine. Trump was eager for the national attention that a big article in a national magazine could bring, and so we spent a good deal of time together. There were a number of aspects of the resulting story that he hated, including, but not limited to, an observation that he had remarkably small (if neatly groomed) hands.

This summer, The New Yorker published a story by Jane Mayer about Tony Schwartz, the co-author of Trump’s book Trump: The Art of the Deal. Mayer wrote that that issue of GQ, with Trump on the cover, was a huge best-seller. She reported that this sale encouraged S. I. Newhouse Jr., the proprietor of this magazine (as well as of The New Yorker), to urge the editors of Random House (which he also owned) to sign Trump up for a book. Which they did. The trouble with this narrative is that the Trump issue of GQ sold hardly at all. At least in the traditional way. Word was, the copies had been bought by him—Trump had sent a contingent out to buy up as many as they could get their hands on. The apparent intention, in those pre-Internet days, was to keep the story away from prying eyes.•