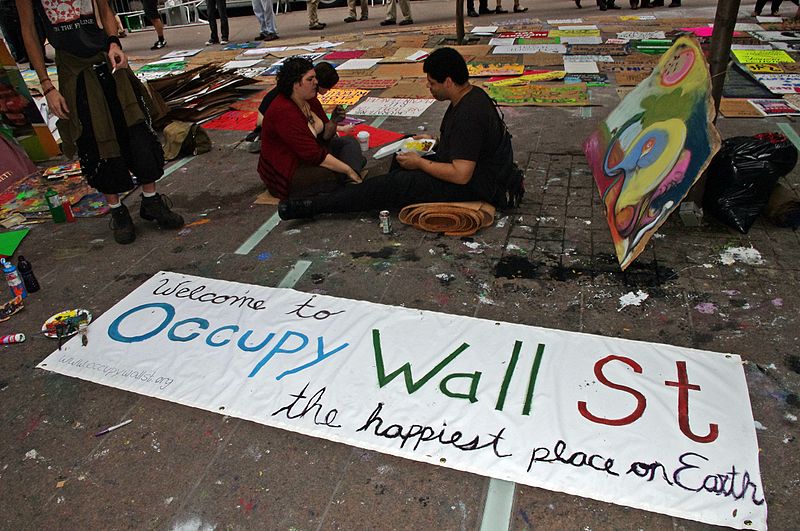

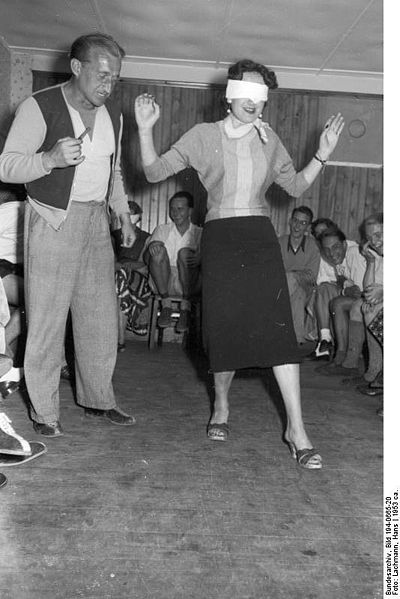

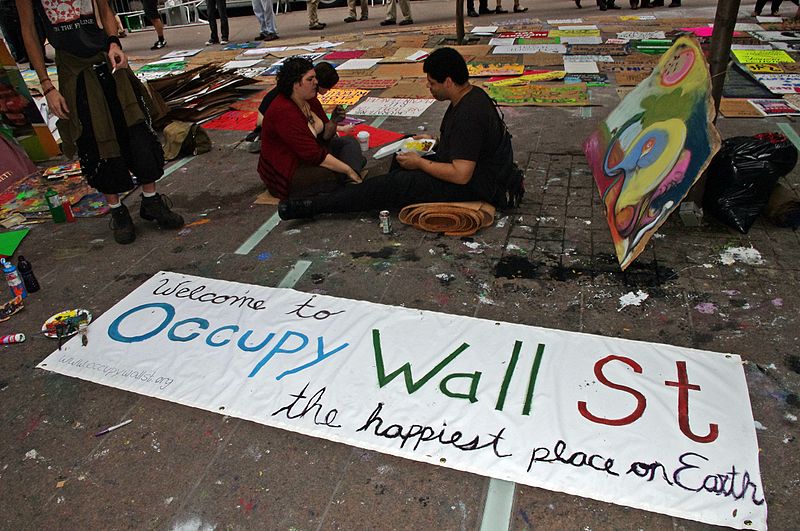

"An ensemble of moving parts, very much in motion, each drawing upon the others and pressing upon them." (Image by David Shankbone.)

The always eloquent and insightful Todd Gitlin analyzes the Occupy Wall Street movement at the Los Angeles Review of Books. An excerpt:

“But movement isn’t a thing. It isn’t, itself, an organization. It doesn’t have officers or headquarters. It’s a verb seeking to be a noun, yet fearful of hardening at the same time, for noun-things solidify, and anarchic energy afoot wants to be liquid, not so much a thing as a process: an ensemble of moving parts, very much in motion, each drawing upon the others and pressing upon them, each making their moves in the light of what others do, an ensemble of movement actors. There’s the inner movement, the outer movement, the politicians, the opposition — and, never forget, the police. They can do you favors, as did the NYPD, first with pepper spray, then with the Brooklyn Bridge mass arrest. But you can’t count on that.

The inner movement has a horizontally organized internal life: an amalgam of task forces and working groups operating under the awkward but so far workable discipline of direct democracy. A common sentiment in the public spaces, as far as I can make out, includes such deep suspicion of representative government — of the very principle of delegation — and such strong faith in the decision-making capacities of ordinary people, as to have invested all legitimate authority in the daily general assemblies.

‘Let the people decide’ was an early sixties slogan, but SDS never coherently knew what it meant, or even worried enough about not knowing. In the late ‘60s, when police bullhorns blared out arrest orders, ‘In the name of the people of California…,’ crowds shouted back, ‘We are the people.’ But we weren’t. In fact, a large majority of the people of California elected Ronald Reagan governor in 1966 and reelected him in 1970. The question of which people get to decide what: This is, of course, the master problem of political theory, and let’s just say I have no triumphant solution to offer here. It’s a problem that doesn’t go away. No matter the urgency, no matter the passion, no matter the circumstance, it just plain doesn’t go away. A serious movement has to be serious about it.”