Question:

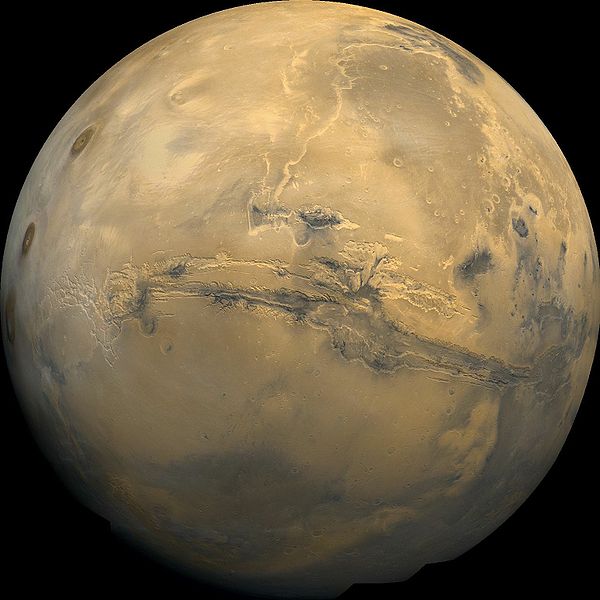

Right now, the first reports are coming back from our probes on Mars. What effect, if any, would news of life on Mars have on humanity?

Philip K. Dick:

You mean the average person?

Question:

Yes. What would it do to their thoughts of themselves, and their place in the universe?

Philip K. Dick:

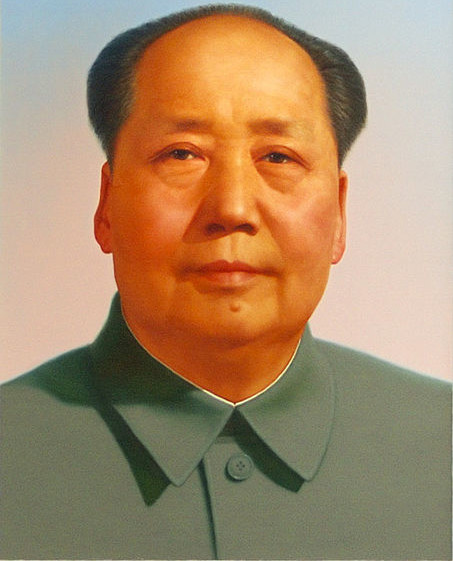

All right. Yesterday, Chairman Mao died. To me, it was as if a piece of my body had been torn out and thrown away, and I’m not a Communist. There was one of the greatest teachers, poets, and leaders that ever lived. And I don’t see anybody walking around with any particularly unhappy expression. There have been some shots of people in China crying piteously, but I woke my girlfriend up at 7:00 in the morning. I was crying. I said, ‘Chairman Mao has died.’ She said, ‘Oh my God, I thought you said ‘Sharon was dead” — some girl she knows. I think I would be like that. I think there would be little, if any, real reaction. If they can stand to hear that Chairman–that that great poet and teacher, that great man, that–one guy on TV — one Sinologist — said ‘The American public would have to imagine as if, on a single day, both Kennedys, Dr. King, and Franklin D. Rossevelt were all killed simultaneously,’ and even then they wouldn’t get the full impact of it. So I don’t really think that to find life on Mars is going to affect people. One time I was watching TV, and a guy comes on, and he says, ‘I have discovered a 3,000,000-year-old humanoid skull with one eye and two noses.’ And he showed it — he had twenty-five of them, they were obviously fake. And it had one eye, like a cyclops, and had two noses. And the network and everybody took the guy seriously. He says, ‘Man originated in San Diego, and he had one eye and two noses.’ We were laughing, and I said, ‘I wonder if he has a moustache under each nose?

People just have no criterion left to evaluate the importance of things. I think the only thing that would really affect people would be the announcement that the world was going to be blown up by the hydrogen bomb. I think that would really effect people. I think they would react to that. But outside of that, I don’t think they would react to anything. ‘Peking has been wiped out by an earthquake, and the RTD — the bus strike is still on.’ And some guy says, ‘Damnit! I’ll have to walk to work!’ So? You know, 800,000 Chinese are lying dead under the rubble. Really. It cannot be burlesqued.

I think people would have been pleased if there was life on Mars, but I think they would have soon wearied of the novelty of it, and said, ‘But what is there on Jupiter? What can the life do?’ And, ‘My pet dog can do the same thing.’ It’s sad, and it’s also very frightening in a way, to think that you could come on the air, and you could say, ‘The ozone layer has been completely destroyed, and we’re all going to die of cancer in ten years.’ And you might get a reaction. And then, on the other hand, you might not get a reaction from people. So many incredible things have happened.

I talked to a black soldier from World War II who had entered the concentration camp — he had been part of an American battalion that had seized a German death camp — it wasn’t even a concentration camp, it was one of the death camps, and had liberated it. And he said he saw those inmates with his own eyes, and he said, ‘I don’t believe it. I saw it, but I have never believed what I saw. I think that there was something we don’t know. I don’t think they were being killed.’ They were obviously starving, but he says, ‘Even though I saw the camp, and I was one of the first people to get there, I don’t really believe that those people were being killed by millions. For some reason, even though I myself was one of the first human’ — notice the words ‘human beings’ — ‘human beings to see this terrible sight, I just don’t believe what I saw.’ And I guess that’s it, you know. I think that may have been the moment when this began, was the extermination of the gypsies, and Jews, and Bible students in the death camps, people making lampshades out of people’s skins. After that, there wasn’t much to believe or disbelieve, and it didn’t really matter what you believed or disbelieved.•