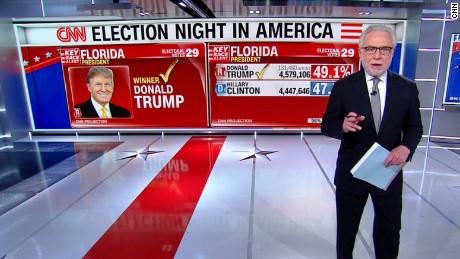

If Hillary Clinton had won a small amount of votes in a few key states, everything would be different, at least outwardly.

The country certainly would have been a million times better off in her hands than in the clutches of an ego-drunk buffoon and his cadre of anti-Semites, sexists and xenophobes. But the distance between a superpower and an also-ran can be razor-thin, and the final tally showed that a frightened populace reached inside for their better angels and came up empty-handed, installing one of the worst among us in the Oval Office. If Clinton had been victorious, she would have been a capable steward who would have offered protections for workers’ rights, but it’s not easy to see what she would have done about manufacturing jobs that aren’t returning even as the factories are re-shored. Machines can handle most of that work now, and not everyone will be able to transition into being a driverless-car engineer. There are no simple answers.

George Packer of the New Yorker has done some great reporting in the pages of that magazine and in The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America on the seismic changes U.S. citizens have experienced (and endured) during this millennium, as the Industrial Age ran out of steam. Two Packer pieces follow about the vanishing of our critical institutions, the second one from his entry in this week’s “Sixteen Writers” feature in the New Yorker.

From 2014:

I began to wonder what a company worker looked like. I found it hard to come up with an image. Amazon’s workforce is made up mainly of computer engineers and warehouse workers, but when you think of Amazon you don’t picture either one (and there aren’t many photographs to help your imagination). What you see, instead, is a Web site with a button that says “add to cart” and a cardboard box with a smile printed on the side. Between clicking “buy” and answering the door when U.P.S. arrives lies a mystery—a chain of events that only comes to mind if you make a conscious effort. The work is done by people you don’t see and don’t have to think about, which is partly what makes Amazon’s unmatched efficiency seem nearly miraculous.

The invisibility of work and workers in the digital age is as consequential as the rise of the assembly line and, later, the service economy. Whether as victim, demon, or hero, the industrial worker of the past century filled the public imagination in books, movies, news stories, and even popular songs, putting a grimy human face on capitalism while dramatizing the social changes and conflicts it brought. The guy stocking shelves and the girl scanning purchases at Target never occupied much of a place in the public mind, and certainly never a romantic one (no one composed a “Ballad of the Floor Associate”), but at least you had to look at them whenever you ventured out to stimulate the economy. They reminded you that low-priced Chinese-made goods were a mixed blessing—that many of the jobs being created in post-industrial America were crappy ones.

With work increasingly invisible, it’s much harder to grasp the human effects, the social contours, of the Internet economy.•

From this week:

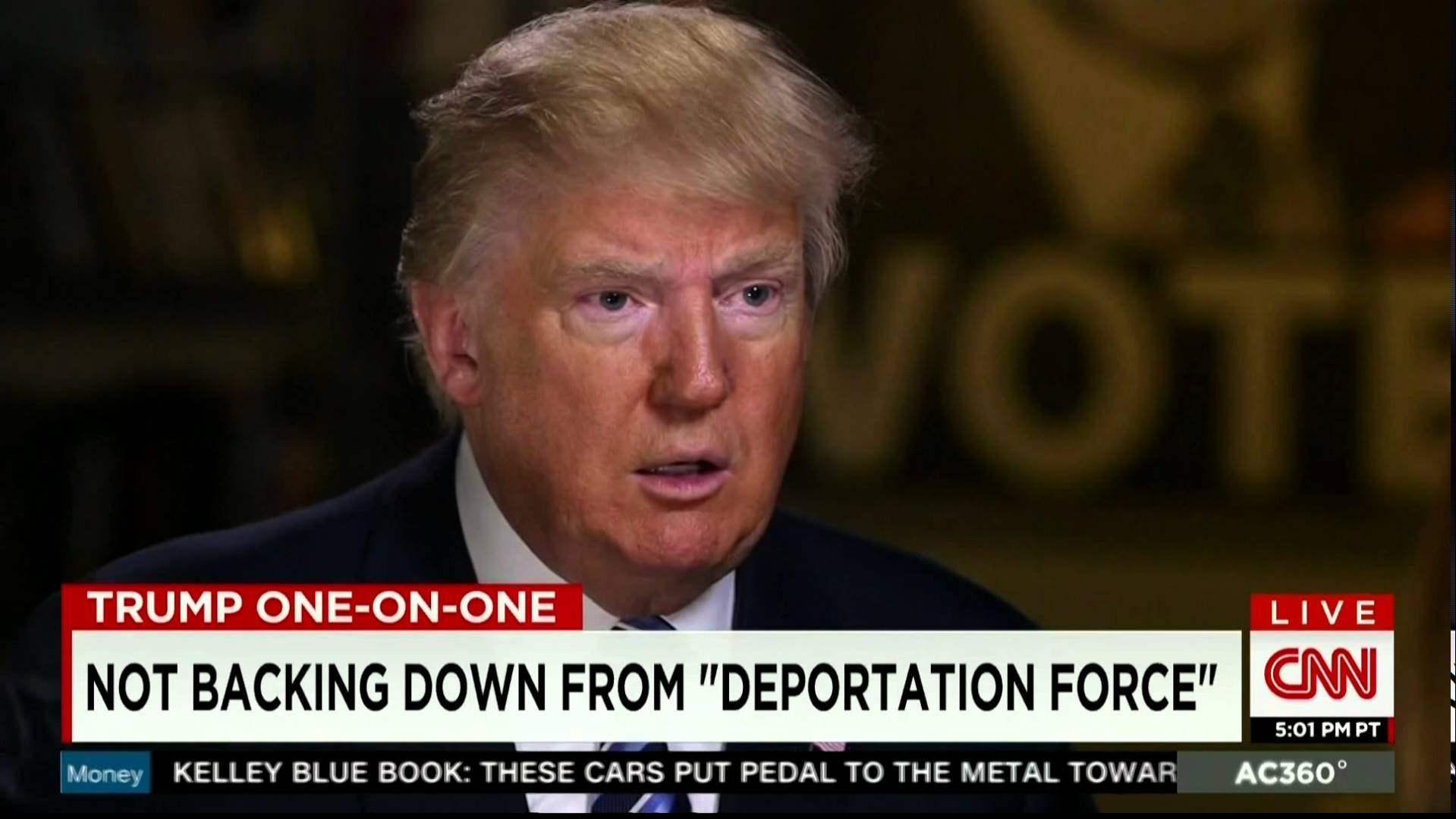

All the pieces are in place for the abuse of power, and it could happen quickly. There will be precious few checks on President Trump. His party, unlike Nixon’s, will control the legislative as well as the executive branch, along with two-thirds of governorships and statehouses. Trump’s advisers, such as Newt Gingrich, are already vowing to go after the federal employees’ union, and breaking it would give the President sweeping power to bend the bureaucracy to his will and whim. The Supreme Court will soon have a conservative majority. Although some federal courts will block flagrant violations of constitutional rights, Congress could try to impeach the most independent-minded judges, and Trump could replace them with loyalists.

But, beyond these partisan advantages, something deeper is working in Trump’s favor, something that he shrewdly read and exploited during the campaign. The democratic institutions that held Nixon to account have lost their strength since the nineteen-seventies—eroded from within by poor leaders and loss of nerve, undermined from without by popular distrust. Bipartisan congressional action on behalf of the public good sounds as quaint as antenna TV. The press is reviled, financially desperate, and undergoing a crisis of faith about the very efficacy of gathering facts. And public opinion? Strictly speaking, it no longer exists. “All right we are two nations,” John Dos Passos wrote, in his “U.S.A.” trilogy.

Among the institutions in decline are the political parties. This, too, was both intuited and accelerated by Trump. In succession, he crushed two party establishments and ended two dynasties. The Democratic Party claims half the country, but it’s hollowed out at the core. Hillary Clinton became the sixth Democratic Presidential candidate in the past seven elections to win the popular vote; yet during Barack Obama’s Presidency the Party lost both houses of Congress, fourteen governorships, and thirty state legislatures, comprising more than nine hundred seats. The Party’s leaders are all past the official retirement age, other than Obama, who has governed as the charismatic and enlightened head of an atrophying body. Did Democrats even notice?•