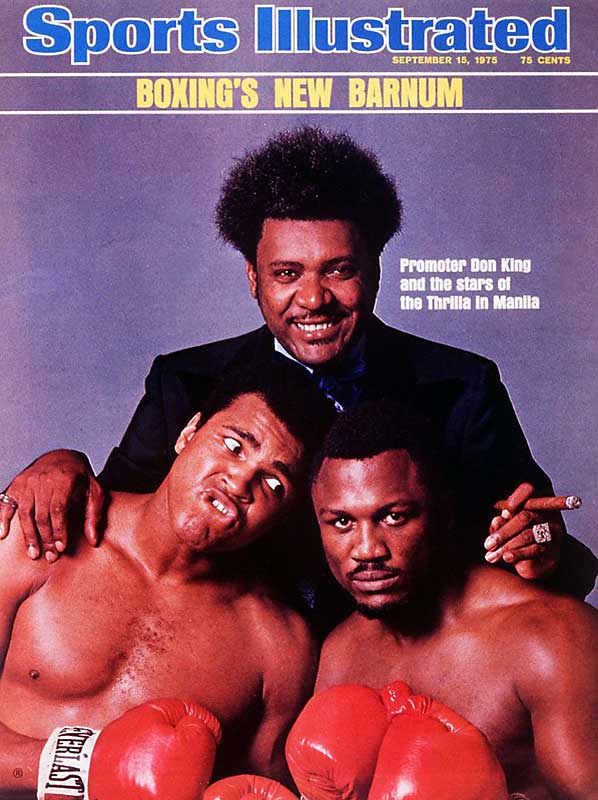

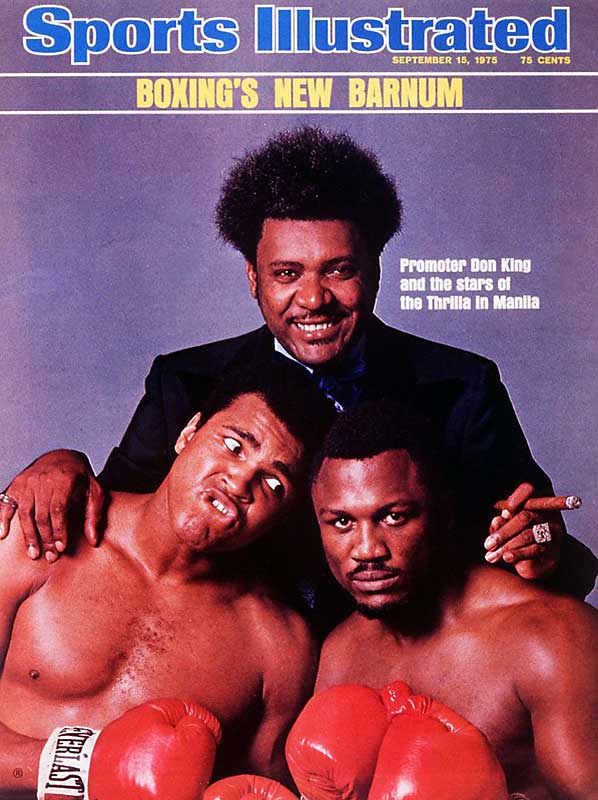

There are plenty of legitimate reasons to dislike Don King, the boxing promoter in decline. He’s a liar and a manipulator and, worst of all, he coldly discarded the very boxers who sacrificed their health for his bottom line, treating them like so many disposable commodities. But none of those character flaws are the main thing that made him so reviled at his apex. He was hated because he dared to be black and a capitalist in an age before rappers perfected the greed-is-good ethos. He didn’t aspire to be twice as good as his white counterparts as African-Americans are often expected to be, but instead hustled his way into the money game, bending and breaking its protean rules, gleefully pointing out that his hands were no dirtier than anyone else’s, just darker. Only in America.

The opening of “The End of Don King,” Jay Caspian Kang’s excellent new Grantland profile of the former national figure in his dotage:

“In the back room of Manhattan’s Carnegie Deli, Don King picked at a pastrami sandwich with his fingers. He had just been asked a question about his electric hair and, for the first time in a day filled with radio and television interviews, King paused before he spoke. A cautious look crept over his graying eyes. As he silently deliberated between several well-worn origin myths about the height of that hair, King tweezed a scrap of pastrami between two well-manicured fingernails and dragged the meat through a puddle of deli mustard. ‘My hair is God’s aura,’ King explained while chewing. ‘Everything went up when I got home from the penitentiary. One night I went to lie down next to my wife and my hair started popping and uncurling all on its own — ping, ping, ping, ping! I knew that it was God telling me to stay on the righteous path so he could one day pull me up to be there with him.”

King smiled, but not the smile you remember. That smile — the screwed-on mask of boundless optimism — had been on full display throughout this week of promotions, but at the Carnegie, King had finally succumbed to exhaustion. ‘When I’m doing good, the hair goes straight up,’ King said, a bit wearily. ‘Now that things are difficult, the hair has gotten a little flatter.’

I had been trailing Don King for two weeks between Boca Raton, Florida, and now New York City. This was the closest he had come to admitting that things just weren’t what they used to be. In three days’ time, Tavoris ‘Thunder’ Cloud, King’s last fighter of any consequence, would step into the ring against Bernard Hopkins at the Barclays Center in Brooklyn. The story of the fight should have been about the 48-year-old Hopkins and his quest to become the oldest champion in boxing history. But because Don King was involved, the focus during fight week had been on Don King and his uncertain future. If Cloud lost to Hopkins — especially in a boring way — his short career as an opponent in televised events would be put in serious jeopardy and King would have very little left to promote. In a pre-fight interview, Hopkins, who, like so many other fighters, had worked with King before an inevitable falling-out, had this to say about his old promoter: ‘What a way to put the last nail in the coffin. Who thought it would be me that would shut him down?’

At the Carnegie, nobody was talking much about Tavoris Cloud or Bernard Hopkins or the impending end of Don King Promotions. King had come to one of his favorite New York landmarks to enjoy a quiet lunch with three longtime employees. They talked, mostly, about music and old times in Manhattan, the city where King lived and worked during the majority of his reign at the top of boxing. The conversation eventually turned to James Brown. Don King, still digging his fingers into his sandwich, muttered, ‘James Brown died owing me $50,000. But I loved James Brown.'”