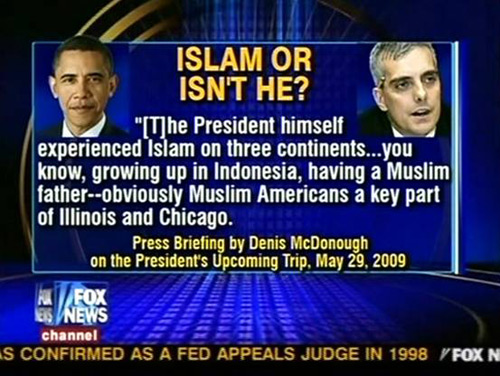

Is the newspaper, that neat product, the anomaly, and the Internet, an ungovernable mess, the norm? From a recent speech by Guardian Deputy Editor Katharine Viner:

“The web has changed the way we organise information in a very clear way: from the boundaried, solid format of books and newspapers to something liquid and free-flowing, with limitless possibilities.

A newspaper is complete. It is finished, sure of itself, certain. By contrast, digital news is constantly updated, improved upon, changed, moved, developed, an ongoing conversation and collaboration. It is living, evolving, limitless, relentless.

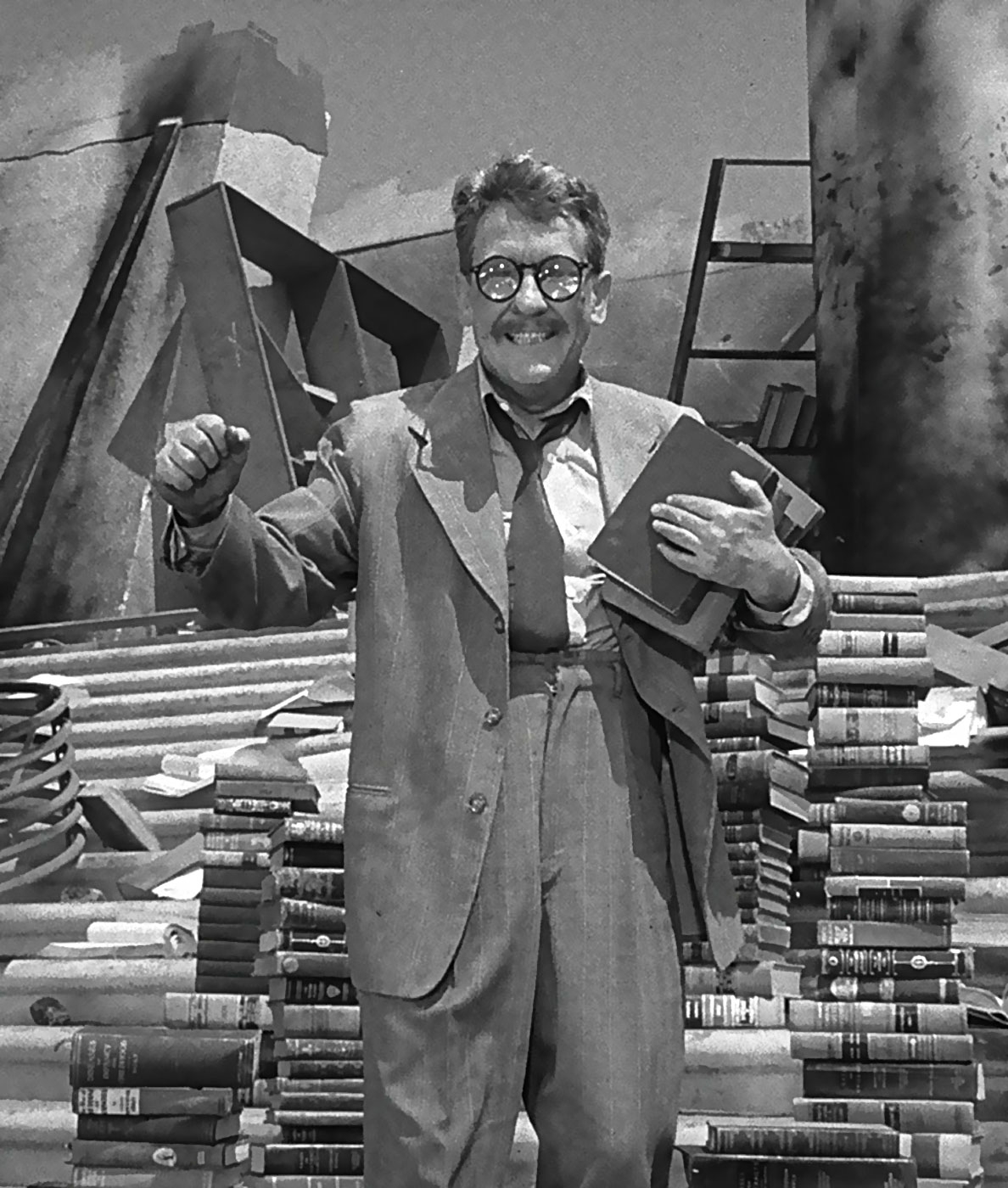

Many believe that this move from fixed to fluid is not exactly new, and instead a return to the oral cultures of much earlier eras. Danish academic Thomas Pettitt’s theory is that the whole period after Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press – of moveable type, the text, the 500 years of print-dominated information, between the 15th and the 20th centuries – was just a pause; it was just an interruption in the usual flow of human communication. He calls this the Gutenberg Parenthesis. The web, says Pettitt, is returning us to a pre-Gutenberg state in which we are defined by oral traditions: flowing and ephemeral.

For 500 years, knowledge was contained, in a fixed format that you believed to be a reliable version of the truth; now, moving to the post-print era, we are returning to an age when you’re as likely to hear information, right or wrong, from people you come across. Pettitt says that the way we think now is reminiscent of a medieval peasant, based on gossip, rumour and conversation. ‘The new world is in some ways the old world, the world before print’ he says.”