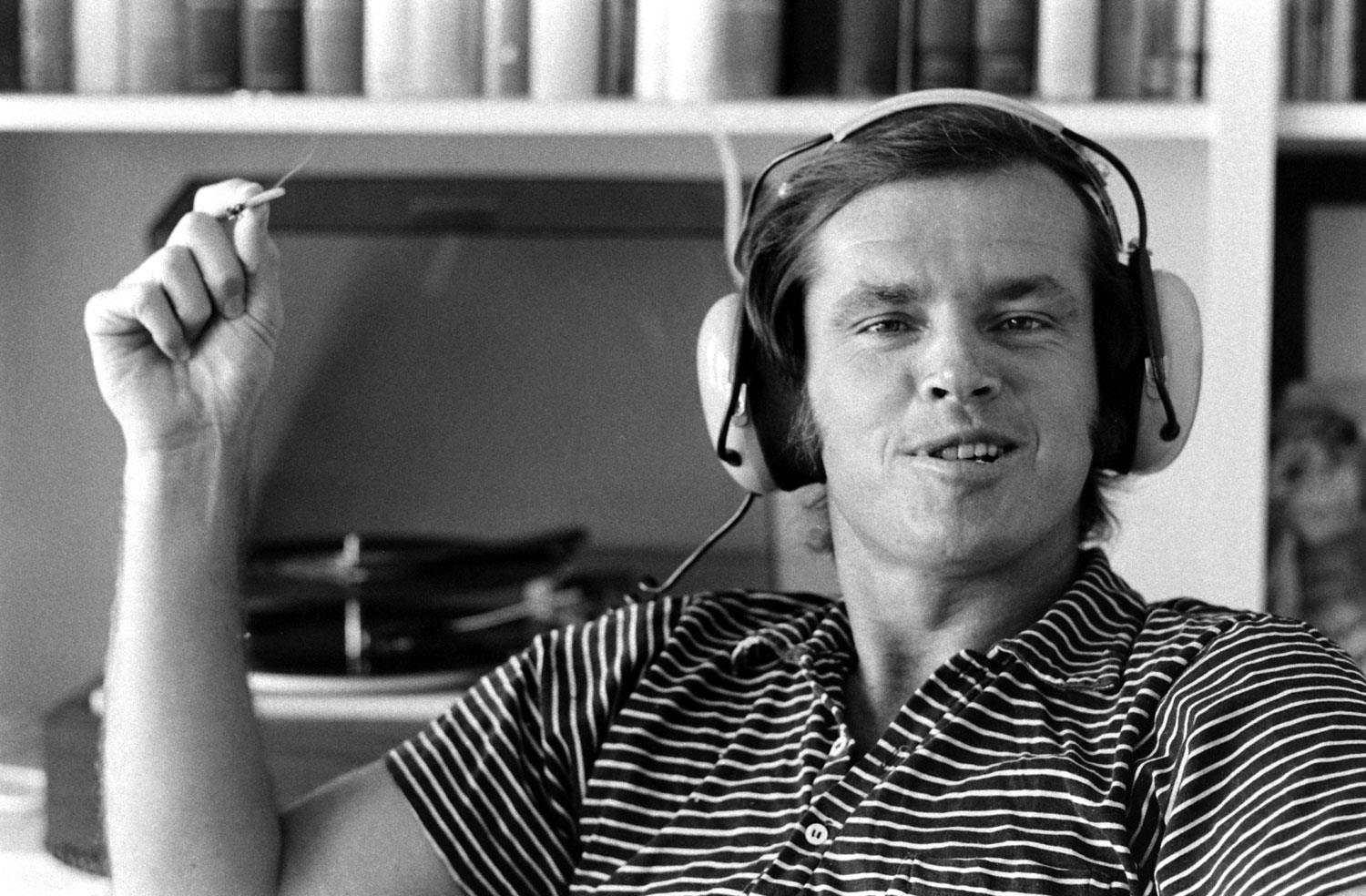

In this post, I used some 1971 photos of Anjelica Huston and Jack Nicholson playing LPs at his Mulholland Drive house, which were taken by the legendary Los Angeles photojournalist Julian Wasser, who is the Weegee of the West, sure, but also a thing all his own, ably adapting to shifting scenes, from street to crime to Hollywood. Wasser just published a book of his work, The Way We Were. Three more of his images follow.

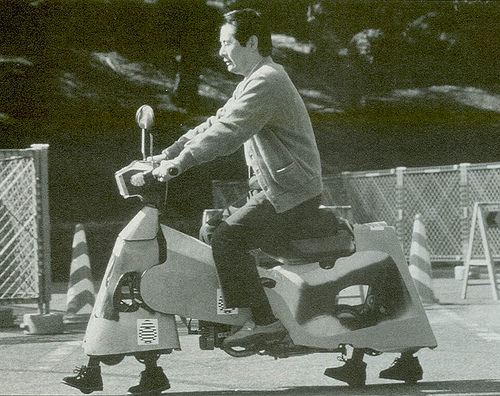

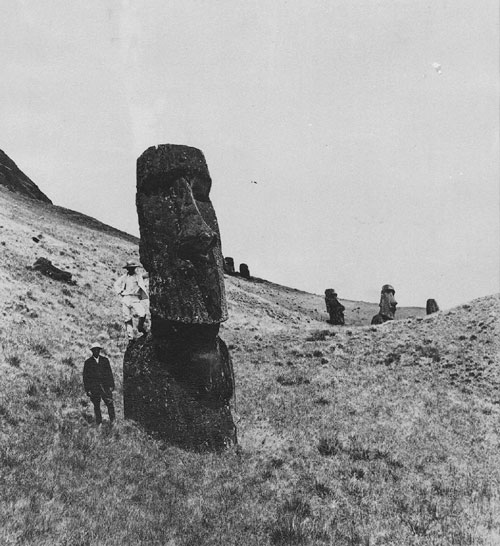

Roman Polanski, 1969

From “Photo Ops,” Dana Goodyear’s excellent W piece:

Wasser’s first real camera was a Contax, which his father gave him when he was a junior in high school in the 1950s. He got himself a scanning radio and tuned in to the frequency used by the police. The first pictures he sold, while still a student at Sidwell Friends, a private Quaker school in Washington, D.C., were of crime scenes. “Crime’s exciting, and it sells,” he says. He got a gig at the Associated Press and met Arthur Fellig, the legendary photographer known as Weegee. “He came in plugging some film,” Wasser continues. “He was my hero.” From Weegee, he learned to use a Speed Graphic. “He was this real gruff, tough, down-to-earth guy, the epitome of a hard-nosed photographer, a street guy on the level of the cops he worked with. He used to beat them to the crime scene.”

That sensibility—an instinct for drama and the decisive moment, the dab of beauty with a smear of grit—put Wasser in the way of news. He was at the Ambassador Hotel the night Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated, and was with the crowd watching as Richard Ramirez, the infamous Night Stalker, was taken into custody by police. In 1969, three days after the actress Sharon Tate was murdered, Wasser, on assignment from Life, went to the crime scene on Cielo Drive with Tate’s husband, Roman Polanski, a pair of detectives, and a celebrity psychic searching for vibrational clues. (The Manson family hadn’t yet been named as suspects.) Wasser took a picture of Polanski, crouched and grim-faced beside a door smudged with fingerprint dust, where the word pig had been written in Tate’s blood. “I felt so bad for Polanski and for being there photographing it,” Wasser remembers. “He was just shattered.” The psychic, meanwhile, stole Wasser’s Polaroids and sold them to the tabs. Later, during the case brought against Polanski for having sex with a minor at Nicholson’s house on Mulholland, Wasser photographed the judge.•

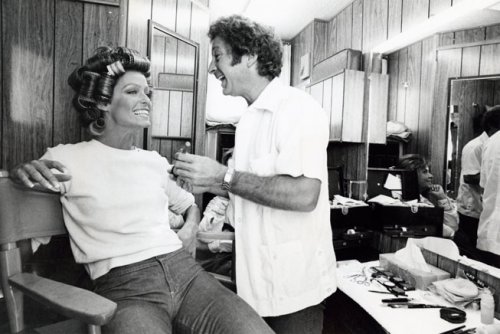

Bernard Cornfeld, mutual-fund manager, and friends, 1974.

From Cornfield’s 1995 New York Times obituary by Diana B. Henriques:

Born in Istanbul in August 1927, Bernard Cornfeld was the son of a Romanian actor who moved his family to the United States in the early 1930’s. He graduated from Abraham Lincoln High School in Brooklyn and Brooklyn College. By 1954, he had become a mutual fund salesman, entering the industry just as mutual funds were experiencing their first strong surge of growth since the stock market crash of 1929.

In 1956, he moved to Paris, planning to sell shares of popular American mutual funds, chiefly the Dreyfus Fund, to Americans living abroad. Using his trademark recruiting challenge — “Do you sincerely want to be rich?” — he built Investors Overseas Services. At its peak, it was a far-flung organization that included a vast and intensely loyal sales force, a secretive Swiss bank, an insurance unit, real estate interests and a stable of offshore investment funds operating beyond the reach of any single country’s securities laws.

By 1970, his company had pumped millions of overseas dollars into the American mutual fund industry, initially through its aggressive sales force and then through Mr. Cornfeld’s trailblazing Fund of Funds, an offshore fund that invested in other mutual funds’ shares.

Mr. Cornfeld gave now-famous money managers like Fred Alger their start by selecting them to run funds owned by the Fund of Funds, which at its peak had more than $450 million invested in American mutual funds.

He also acquired enough financial power over American mutual funds and skirted close enough to the edges of Federal securities laws to attract the attention of the Securities and Exchange Commission, which in 1965 accused him and his company of violating American securities laws.

In 1967, the company settled the commission’s complaint by agreeing to wind up or sell all its American operations. The Fund of Funds also agreed to buy no more than 3 percent of any American mutual fund, the limit imposed by Federal mutual fund law.

After leaving the American market, Mr. Cornfeld continued to live lavishly, and his financial empire appeared strong until early 1970, when it suddenly disclosed that it was short of cash and had substantially overestimated its 1969 profits.•

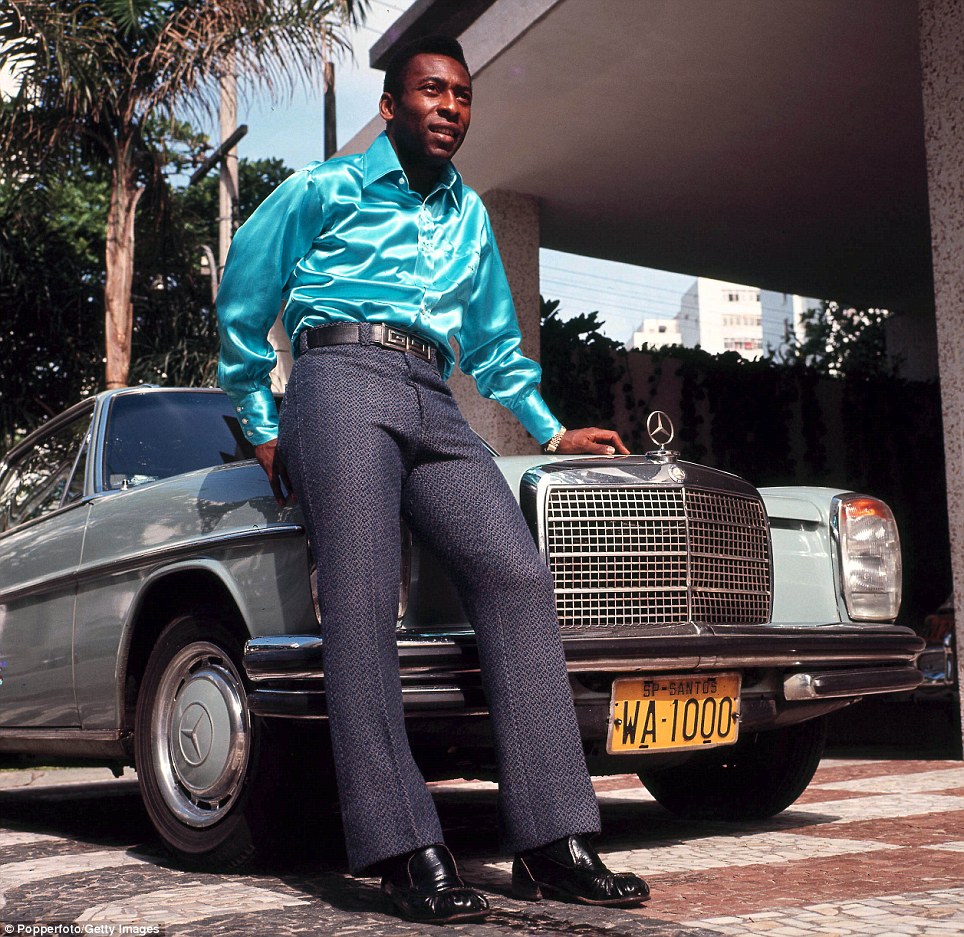

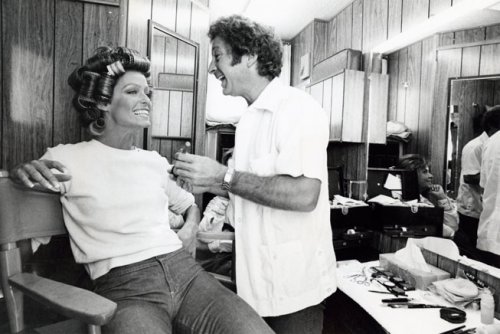

Farrah Fawcett, 1976.

The opening of “Super-Powered Love,” Lois Armstrong’s 1976 People article:

It would take a network in a ratings crisis to create a six million dollar man, with one telescopic-zoom eye and three nuclear-powered prosthetic limbs—the role Lee Majors plays so stoically on ABC every Sunday night. But, still mercifully, only God can make a Farrah Fawcett-Majors, as Lee’s offscreen wife calls herself. “She’s so gorgeous,” Majors glows, “she’s like a little girl. So cute, so beautiful inside, you wanna…” His natural reticence stifles further elaboration. The whole preposterousness of his series and its success (it shot from the Nielsen cellar last season to No. 5) may also have gotten to his brain and consciousness—which never were exactly “bionic.”

Farrah’s looks are indeed breath-stopping, and her own career is rocketing in commercials (Noxzema, Wella Balsam, Ultra-Brite); TV (as David Janssen’s girl next door on Harry O plus a starring part in a pilot); and film (playing with Michael York in the upcoming Logan’s Run). So, when queried about having children, Farrah replies, yes, but not for a couple of years, and Lee quips, “We already have bids from people who would like to have pick of the litter.”

In the meantime, Majors has begat, if nothing else, a spin-off series premiering Jan. 14 that he calls The Bionic Rip-Off—the official ABC title is The Bionic Woman. Lee’s dubiousness owes to the fear that the new show could dilute the Six Million Dollar Man ratings already perhaps in jeopardy. Part of Majors’ rise can be attributed to this fall’s plop from favor of his CBS competition, Cher, but she is almost certain to make at least a one-week Nielsen rebound next month among viewers curious to see the return of ex-husband Sonny, not to mention the TV premiere of her now gravid midriff. Lee may also begrudge the sweeter contract the bionic female, actress Lindsay Wagner, has chivied out of Universal. She, unlike Majors, negotiated a sizable share of any merchandising royalties—Six Million Dollar Man dolls were supposedly the hottest item in toy biz at Christmas, and he barely collected a pittance. Lindsay was also guaranteed five feature films—which could rankle Lee, because he blames his TV stereotyping for thwarting his own movie career.

Majors, 36, professes to be less threatened by his wife’s sudden stardom at 28—as long as it doesn’t interfere with her cooking his nightly supper.•