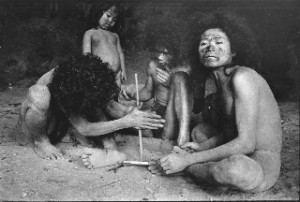

Hoaxes that work do so because they play upon a deep-seated fear or satisfy a psychological want–a need, even. That’s why we’re able to suspend disbelief about something that seems ridiculous in retrospect. When I published the post about a passage from Daniel Lieberman’s recent book, The Story of the Human Body, it reminded me that he (briefly) touches on the story of the Tasaday people, a “stone-age” tribe discovered in 1971 in Philippine caves, which was untouched by wars hot and cold, threats of nuclear disaster, and trends in which clans–families–were unable to stay together. It was a sensation that National Geographic granted a cover and a 32-page story, and, of course, it was a hoax. But it had a good, long run, with Charles Lindbergh himself spending some of his final moments of life writing the foreword for a popular book about this make-believe people. The opening of a 1986 New York Times article by Seth Mydans, written when the work finally began to stop working:

“MANILA, May 12— After more than a decade, scientists and reporters have returned to visit a remote Stone Age tribe called the Tasaday, and found that its earlier contacts with the outside world have set it on what appears to be an irreversible road to change.

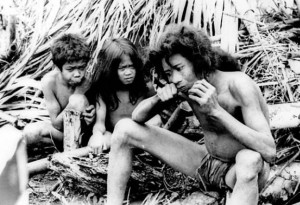

The new visits have also reopened a debate on the authenticity of the Tasaday, who have now been found to possess bits of clothing, knives, bows and arrows, a mirror and domesticated dogs.

In interviews, two anthropologists who recently revisited the tribe said these new possessions, which had aroused the scepticism of Swiss and German reporters who saw them recently, were an expectable product of the tribe’s first contacts with outsiders in the early 1970’s.

Discovered in 1971

The scientists said they now feared that, if new protective measures were not taken, an influx of researchers, journalists and tourists would destroy their fragile way of life, already imperiled by the approach of loggers, slash-and-burn farmers and the armed insurgencies that share the forests of the southern Philippine island of Mindanao.

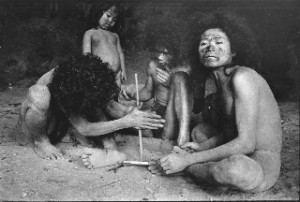

The Tasaday, a group of fewer than 30 people, were discovered in 1971 and drew international attention as a cave-using tribe of hunter-gatherers who dressed in orchid leaves and bark, knew no enemies and had no words for war, for ocean or for other peoples.

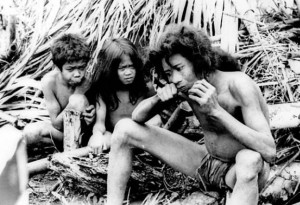

When two groups of journalists trekked into the jungle recently, they found the tribe members wearing bits and pieces of clothing and displaying other signs of outside influence, and the visitors raised cries of ‘hoax’ and ‘fairy tale.’

The two anthropologists who visited soon afterward, however, in the company of John Nance, author of a book on the tribe, and a television crew, said the changes were not surprising, and indeed enhanced the scientific interest of the group.

‘Textbook Case of Change’

‘We’re seeing a textbook case of social change, compressed in time,’ said one of the anthropologists, Jesus Peralta, who is curator of anthropology for the National Museum of the Philippines.

The other anthropologist who visited, Carlos Fernandez, said, ‘Before we first met them, they were purely forest gatherers.’

‘Then they learned to use a blade, to set traps and now they are learning to hunt,’ he went on. ‘Before long they will try their hand at planting.

‘This is one of the most exciting subjects for an anthropological investigator.’

Mr. Nance, the author of The Gentle Tasaday, who traveled last month to Mindanao with the two anthropologists, said the Tasaday’s preference for T-shirts and other articles of clothing was only natural. ‘If leaves were better, we’d all be wearing leaves,’ he said. Brides From Another Tribe

The scientists said the question of a hoax had always been present and remained a possibility. But they said such details as the stone tools and the language used by the Tasaday would be extremely difficult to fabricate.

‘Unless another anthropologist produces conflicting data, then the literature stands,’ said Mr. Peralta.

Many of the changes were thought to be the result of two outside influences: a tribal hunter named Dafal, and the marrying of women from a nearby tribe called the Blit.

A small group of primarily male cousins, the Tasaday’s main request of the scientists who discovered them was for brides. Mr. Peralta said that, in the years since then, 15 Blit women and two men had married into the tribe.

Trapping and Weapons

Dafal and the Blit spouses brought with them clothing, beads, knives, rice and cigars, the scientists said.

They also said they taught them to trap and use bows and arrows to supplement their traditional diet of yams, the hearts of palms and rattan, and fish, frogs and tadpoles.

‘They were already in transition when we first met them,’ Mr. Nance said, referring to their earlier contacts with Dafal. ‘Scientists worked to reconstruct what their life had been like before that, and people took the reconstruction as the current reality.’

He said this had led to misconceptions and to the recent accusations of a hoax.”