Two excerpts follow from John Weaver’s 1970 Holiday profile of the Hollywood Hills in flux, written at a time when fading early-film stars were joined in the smoggy gorgeousness by newly minted rock royalty, hippie cults, motorcycle gangs, and, worst of all, clinical psychiatrists.

_____________________________

Each of the through canyons—Laurel, Coldwater, Benedict, Beverly Glen—has its own distinctive personality.

Laurel is Southern California’s semi-tropical version of Manhattan’s East Village. Mediterranean villas dating back to the first hoarse days of talking pictures are hemmed in by dilapidated shacks owned by absentee landlords. The canyon’s natural fire hazards have been intensified of late by shaggy young nomads who turn on in the blackened ruins of burned-out mansions where Theda Bara may once have dined. The daily life of the community swirls around a small shopping center, “The Square,” which boasts the old-fashioned Canyon Country Store and a pleasant cafe, the Galleria.

Coldwater and Benedict are more sedate and affluent (their watering hole is the Polo Lounge of the Beverly Hills Hotel). When a newcomer to the community set out to cast his vote in the last municipal election, he was somewhat taken aback to find his polling place was a home in the $150,000-to-$200,000 class. The booths faced the pool.

“I half-expected to have my ballot served by the butler,” he recalls.

One of the most curious sights of his new surroundings, he has found, is the dawn patrol of stockbrokers and speculators who, because of the three-hour time differential between the East and West Coasts, can be seen silhouetted against the sunrise as their Cadillacs and Continentals lumber down the hills in time for the first ticker-tape reports from Wall Street.

To the west, near the sprawling campus of the University of California at Los Angeles, lies Beverly Glen, the friendliest of all the canyons, as tourists discover when they stop for dinner at its charming wayside inn, the Four Oaks. The Glen has the feeling of a sycamore-shaded residential street in a rural college town. Associate professors and graduate students live cheek-by-jowl with a mixed lot dominated by the professions and the arts.

“The Glen defies any kind of rational analysis,” says Jack Thompson, veteran leader of its homeowner organization. “Take the houses on my street, for instance. They’re occupied by a computer sciences teacher, a rock singer, a furniture man, an attorney, a sprinkler equipment salesman, an actress and a clinical psychiatrist.”

Historically, the Hills have been hospitable to the indulgence of individual tastes, no matter how bizarre, but at times one man’s life style encroaches on his neighbor’s, as the Benedict Canyon Association discovered when it began to get complaints from members who found themselves living downwind of a stable. In Coldwater, the neighboring canyon to the east, homeowners banded together to block Frank Sinatra’s application for a private helistop. The singer finally gave up on Los Angeles and headed for the desert.

“The air isn’t fit to breathe, so I’m clearing out,” he announced in the fall of 1968, and a year later he got support from, of all places, the coroner’s office. The body of a young woman, stabbed to death, was found in the hills not far from Sinatra’s abandoned retreat. The dead girl was new to Southern California, the coroner deduced, because her lungs showed none of the ill effects of smog.

_____________________________

A mile-long stretch of county territory with a gamey history (it was Hollywood’s place to drink and gamble during Prohibition), the Strip has become a children’s playground where middle-aged tourists in slow-moving Gray Line buses peer out in horror at the outlandish getups of the young, many of whom have fled the same wall-to-wall certainties about soap and success to which the tourists will return, unchanged. (Mother, to Aunt Martha: “They looked half-starved, poor things. Goodness knows what they eat.” Father, to Uncle Fred: “The girls wore these little skirts up to here and blouses you could see through, and not a thing underneath, not a thing.”)

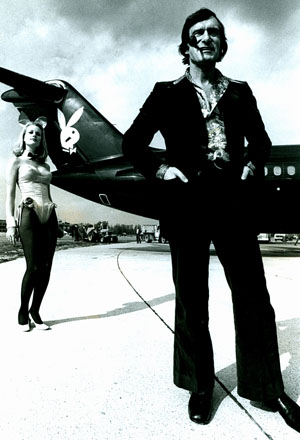

Homes in the hills above the action, once the property of men with ulcers and wall plaques attesting to their ability to peddle cars or endowment policies are now sprouting For Sale signs. (In the Sunday papers they are advertised as “Swinger’s Pad,” “Artist’s Retreat” and “Funky Mediterranean.”) Large areas are being surrendered to motorcyclists, call girls and young couples of every known sexual persuasion (the enclave is referred to in heterosexual circles as “The Swish Alps”).

The Strip has become a buffer zone between the hippie communes of Laurel Canyon and the marble resting places of moneylenders and paving contractors who look down on Beverly Hills from the majestic heights of Trousdale Estates. The Beverly Hills border separates young swingers who are making out from elderly plastics who have it made.

The two generations live side by side in the high-priced side streets off Coldwater and Benedict Canyons, where Charlton Heston works out in the pool of his stone fortress and Harold Lloyd plays golf on a multimillion-dollar estate a brisk canter from Tom Mix’s old spread. Valentino tried to win back his second wife by sinking a borrowed fortune in a hillside place where, he said, he wanted his friends “to remember me as permanently fixed on a set at last.” His Falcon’s Lair, now the property of Doris Duke, is a short walk from the Benedict Canyon estate where Sharon Tate, three friends and a young passerby were slaughtered last August.

The separate worlds of Benedict Canyon and the Sunset Strip coexisted on Sharon Tate’s rented estate. The international film crowd bounded up Cielo Drive in sports cars to groove in the main house (“In my house there were parties where people smoked pot,” Miss Tate’s husband said afterwards. “I was not at a Hollywood party where someone did not smoke pot”).

“The poshest homes on the quietest lanes of all of the better canyons are often as not, symbolically, boarding houses, whose leases or titles are written in a kind of quick-fading ink,” Charles Champlin, the Los Angeles Times entertainment editor, wrote after the tragedy. “They are way-stations on the way up or down, in or out.”

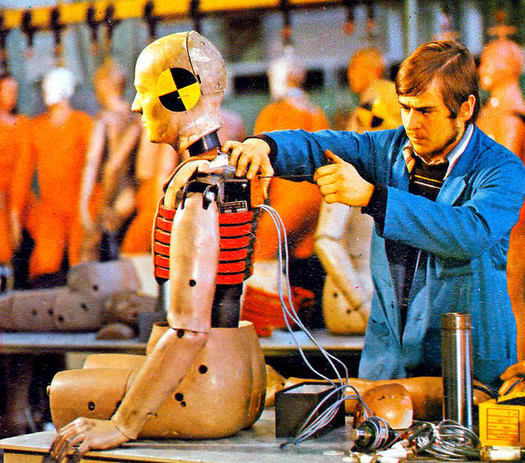

“The stars move out,” a Beverly Hills realtor once remarked to a New York Times reporter, “and the dentists and psychiatrists move in.”•