I feel fairly certain that if humans reached our endgame on Earth at this moment, if we met, say, with the business end of an asteroid, and if anthropologists from some distant galaxy someday studied us, one of the things they would find most surprising, perplexing, and even endearing, is that oracles in a place called Hollywood spent hundreds of millions of dollars making individual comic-book movies, one after another, that they essentially engaged in celluloid nation-building. It’s insane–and understandable, given the economics of our globalized world. I have no interest in the product itself, no concern for Han Solo or the Hulk, so I am left to ponder other implications. Mark Harris does the same in his latest Grantland article, “The Birdcage,” which focuses on the year the film industry completely surrendered to the blockbuster. An excerpt:

“That’s not where we are anymore. In 2014, franchises are not a big part of the movie business. They are not the biggest part of the movie business. Theyare the movie business. Period. Twelve of the year’s 14 highest grossers are, or will spawn, sequels. (The sole exceptions — assuming they remain exceptions, which is iffy — are Big Hero 6 and Maleficent.) Almost everything else that comes out of Hollywood is either an accident, a penance (people who run the studios do like to have a reason to go to the Oscars), a modestly budgeted bone thrown to an audience perceived as niche (black people, women, adults), an appeasement (movie stars are still important and they must occasionally be placated with something interesting to do so they’ll be cooperative about doing the big stuff), or anecessity (sometimes, unfortunately, it is required that a studio take a chance on something new in order to initiate a franchise). A successful franchise is no longer used to finance the rest of a studio’s lineup; a studio’s lineup is brands and franchises, and that’s it. Disney, of all the big companies, is the closest to approaching the absolute zero of this ideal — its movies are virtually all branded, whether Lucasfilm, Pixar, Marvel, or Walt Disney Studios — and anyone who doesn’t imagine that other studio CFOs are gazing at that model in envy and wonder is delusional. Disney is a kingdom of subkingdoms. Nothing minor or modest need apply.

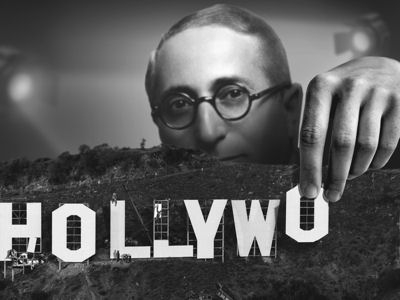

Every generation of studio titan is less apologetic than the one before. In Hollywood’s first golden age, the studios were run by shrewd, canny, undereducated first- or second-generation Americans — crass businessmen who claimed to love Art; they maintained offices in New York City where they deputized aides to elevate the tawdry screen trade from lowbrow to middlebrow by purchasing legitimacy in the form of the best-reviewed new novels and most acclaimed Broadway plays. God bless them every one; their aspirationalism built Hollywood. Decades later, once movies themselves had become a central and even revered part of the culture, that era of mogul gave way to a new breed: the bottom-line businessman who loved movies as long as they were entertaining, but was still willing to reassure doubters that he occasionally liked Art, too, up to a point and in small doses. They still had enough old-Hollywood DNA to feel an obligation to tithe: A modest portion of their profits would always be used to take gambles on the kind of great hopes that didn’t always translate to bottom-line success.

Today we have a different model: The modern studio chief loves business, success, replication, and reliability, and nobody expects him to offer even the most cursory nod to anything that smacks of ideals that relate to content; that’s not what he’s there for.”