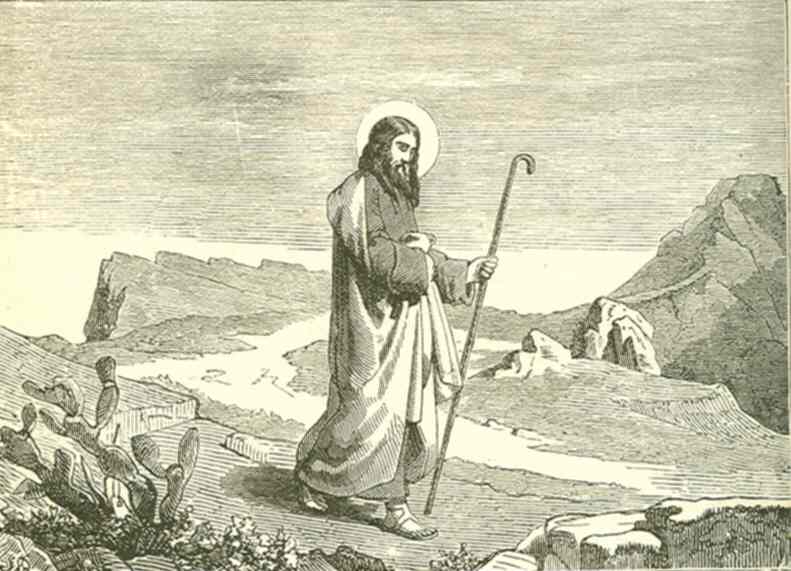

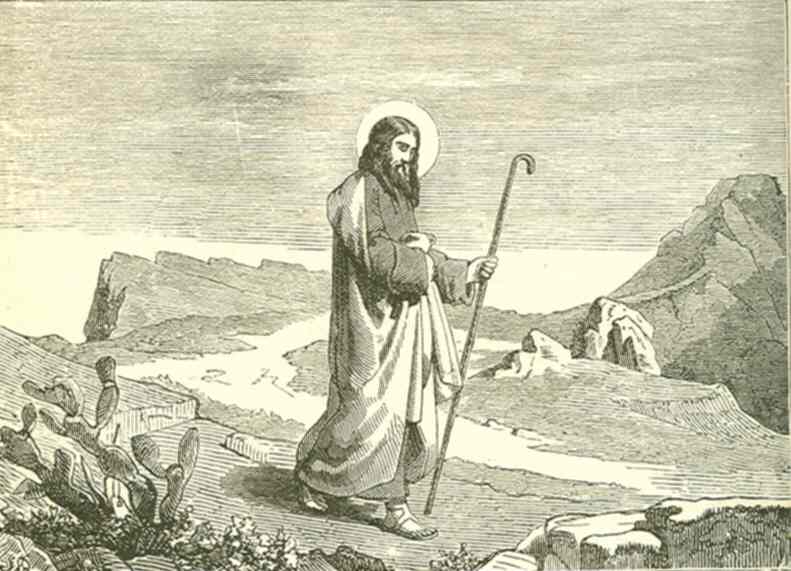

“He gravely announced himself as the ‘Spirit of Truth,’ being the Matthias mentioned in the Scriptures who had risen from the dead.”

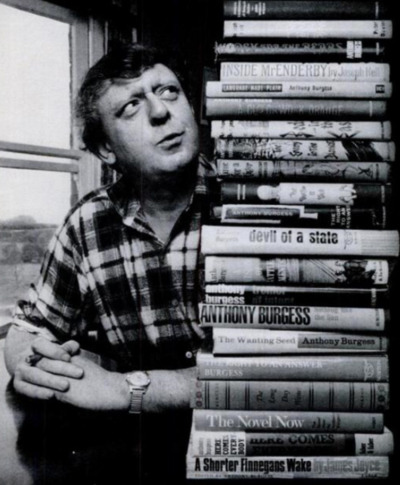

Gilbert Seldes’ magnum opus, The Stammering Century, first published in 1928, is the true story of the stranger-than-fiction twists and turns that religion took in 19th-century America, as it splintered into cults and manias, driven by charismatic mountebanks who passed themselves off as messiahs. (In that sense, it’s much like our age.) One section focuses on New York-based Robert Matthews (a.k.a. Robert Matthias, Jesus Matthias, etc. ), a struggling carpenter who in the 1830s managed to convince a band of wealthy Baptist apostates to make him the head of their crazy, cult-like sect, “The Kingdom.” From “The Impostor Matthias” in the December 25, 1892 New York Times:

“The delusions of the period, thus far harmless, had assumed a progressive character that was destined to develop rapidly to a tragical conclusion. Among the leading spirits of the ‘Holy Club’ was a Mrs. Sarah Pierson, whose husband, Elijah Pierson, was a successful and highly respected merchant. She was a woman of wide culture and engaging manners, and the couple were among the most esteemed members of the Baptist society of that day. They resided on Bowery Hill, an agreeable suburb of New York, sixty years ago, somewhere in the vicinity of the present Madison Square. In this rural locality were situated, on a breezy, shaded eminence, a number of handsome houses, the summer residences of the well-to-do merchants of that period.

In the year 1828 Mr. Pierson came to regard himself as being in constant direct communication with the Almighty, through the agency of the Holy Spirit, and his wife being equally impressed with his divine associations, the operations of the Christian world were too slow for their heated imaginations, and in 1829 they withdrew from their affiliation with the Baptist Church and organized an independent religious society, with a nucleus of twelve members, which they called ‘The Kingdom.’ Meetings were held daily and often twice a day in the Pierson residence on Bowery Hill, brief intervals only being allowed for sleep and light refreshment. The labors and vigils of the new faith, together with the protracted seasons of entire fasting, broke down the health of Mrs. Pierson, and in June, 1830, her husband having, while riding one day down Wall Street in an omnibus, received the Divine command in these words: ‘Thou art Elijah, the Tishbite. Gather unto me all the members of Israel at the foot of Mount Carmel,’ anointed her with oil from head to feet in the presence of the assembled elders of ‘the Kingdom.’ A few days later the unfortunate woman died.

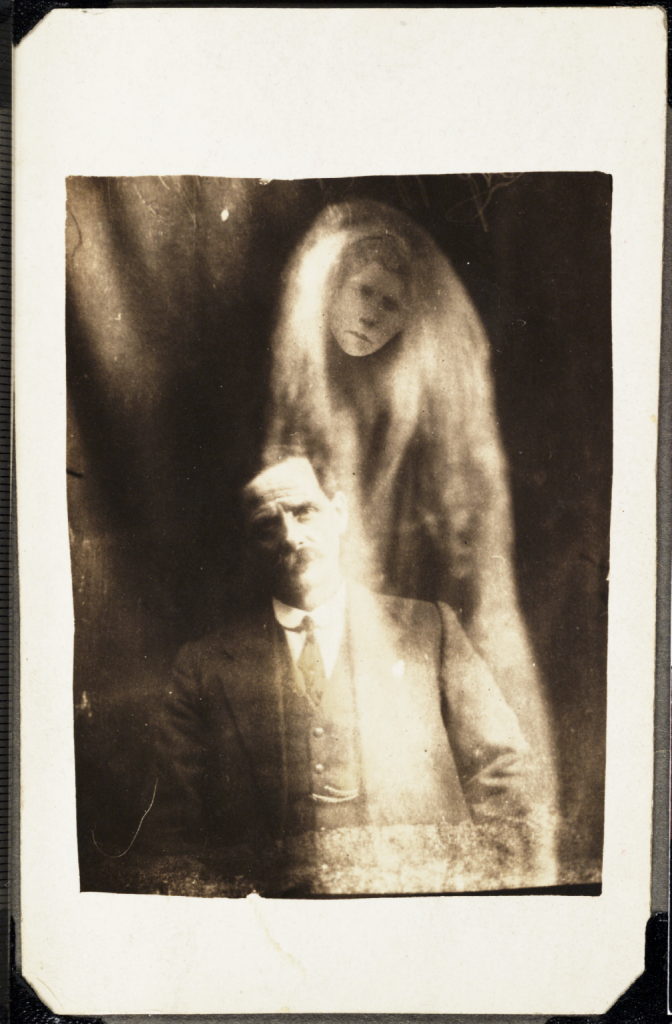

“The delusion that his beloved wife was still to be raised from the dead possessed the unhappy husband’s mind for many months afterward.”

On the day of the funeral, about 200 persons being in attendance, Mr. Pierson endeavored to effect the miracle of her resurrection, attributing his failure to the lack of faith of the bystanders. The scene was harrowing in the extreme, and the delusion that his beloved wife was still to be raised from the dead possessed the unhappy husband’s mind for many months afterward. In 1831 Mr. Pierson removed to a spacious house in Third Street, where he held forth daily to the elect of ‘The Kingdom,’ which now numbered quite a large congregation of converts, some, indeed, being attracted from points outside the city. Among the latter were a Mr. Benjamin Folger and his wife, persons of wealth and standing, who had recently removed their residence from New-York to a handsome country place, near Sing Sing, or Mount Pleasant, as the place was then designated. Another conspicuous member of the strange association was a Mr. Sylvester H. Mills, a well-to-do Pearl Street merchant–a man whose naturally gloomy temperament had been intensified by the death of a beloved wife, a few months previous to the decease of Mrs. Pierson. These people, with many others of all social grades, gathered about Mr. Pierson, to listen to his denunciations of the churches, and his exhortations to place their faith in the Lord in order that, like the Apostles, they might be enabled to ‘heal the sick, cast out the devils, and raise the dead.’

While those extravagances were in progress and the inflamed imaginations of the fanatical leaders were worked up to a high pitch of expectancy, there appeared among them on May 5, 1832, a stranger, whose pretensions, while according with the tenor of their diseased minds, were so far in advance of their own most enthusiastic flights that he was at once accepted as their leader, and worshipped as a divine being. He gravely announced himself as the ‘Spirit of Truth,’ being the Matthias mentioned in the Scriptures who had risen from the dead and possessed the spirit of Jesus Christ. He further declared that he was God the Father, and claimed power to do all things, to forgive sins, and to communicate the Holy Ghost to such as believed in him.

A short account of the previous history of this singular character is necessary at this point, in order to explain how he came to fasten himself thus on ‘The Kingdom,’ with his monstrous claims of divine powers. His name was Robert Matthews, and he was born in Washington County, New York, about the year 1790. He followed the trade of carpentering, and in 1827 he lived in Albany, where he was known as a zealous member of the Dutch Reformed congregation, over which Dr. Ludlow presided. Happening to attend a service conducted by a young clergyman named Kirk, who was visiting Albany from New-York City, he returned home in a state of great excitement, and sat up all that night discussing the sermon he had heard. His enthusiasm was so great that his wife remarked during the night to her daughter: ‘If your father goes to hear that man preach any more he will become crazy.’ He did go to hear him a number of times, and the reader may gather from the sequel of this story whether the wife’s prediction was fulfilled.”