Lee Billings, author of the wonderful and touching 2014 book, Five Billion Years of Solitude, is interviewed on various aspects of exoplanetary exploration by Steve Silberman of h+ Magazine. An exchange about what contact might be like were it to occur:

Steve Silberman:

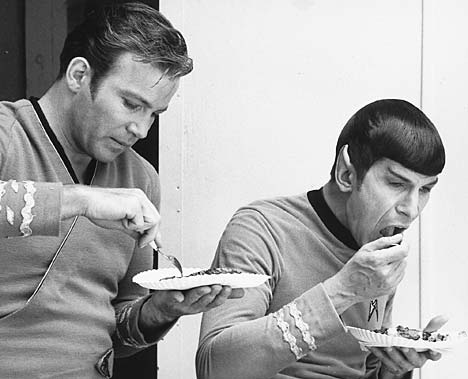

If we ever make contact with life on other planets, they will be the type of creatures that we could sit down and have a Mos Eisley IPA or Alderaan ale with — even if, by then, we’ve worked out the massive processing and corpus dataset problems inherent in building a Universal Translator that works much better than Google? And if we ever did make contact, what social problems would that meeting force us to face as a species?

Lee Billings:

Outside of the simple notion that complex intelligent life may be so rare as to never allow us a good chance of finding another example of it beyond our own planet, there are three major pessimistic contact scenarios that come to mind, though there are undoubtedly many more that could be postulated and explored. The first pessimistic take is that the differences between independently emerging and evolving biospheres would be so great as to prevent much meaningful communication occurring between them if any intelligent beings they generated somehow came into contact. Indeed, the differences could be so great that neither side would recognize or distinguish the other as being intelligent at all, or even alive in the first place. An optimist might posit that even in situations of extreme cognitive divergence, communication could take place through the universal language of mathematics.

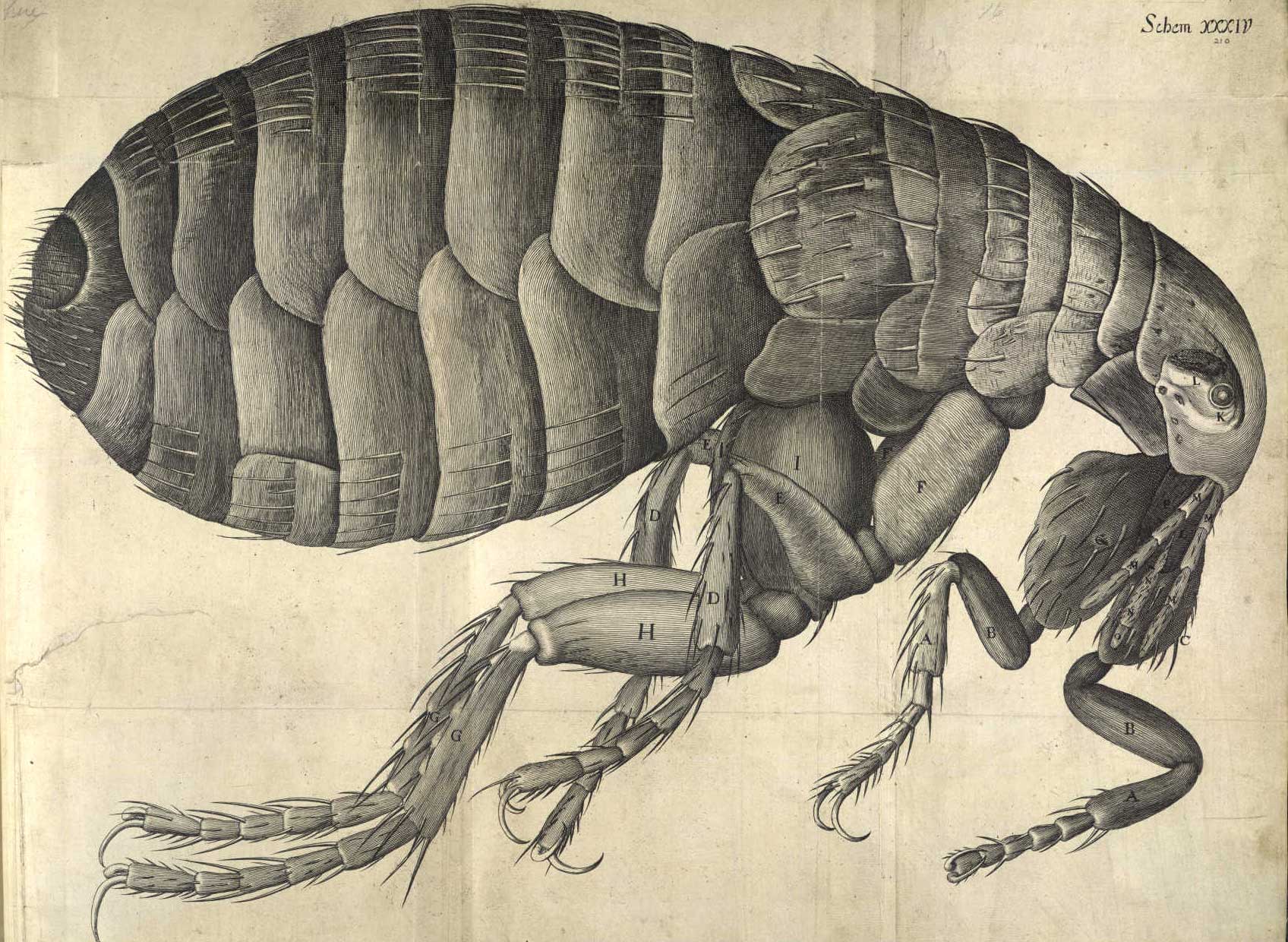

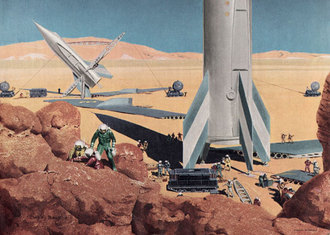

The second pessimistic take is that intelligent aliens, far from being incomprehensible and ineffable, would be in fact very much like us, due to trends of convergent evolution, the tendency of biology to shape species to fit into established environmental niches. Think of the similar streamlined shapes of tuna, sharks, and dolphins, despite their different evolutionary histories. Now consider that in terms of biology and ecology humans are apex predators, red in tooth and claw. We have become very good at exploiting those parts of Earth’s biosphere that can be bent to serve our needs, and equally adept at utterly annihilating those parts that, for whatever reason, we believe run counter to our interests. It stands to reason that any alien species that managed to embark on interstellar voyages to explore and colonize other planetary systems could, like us, be a product of competitive evolution that had effectively conquered its native biosphere. Their intentions would not necessarily be benevolent if they ever chose to visit our solar system.

The third pessimistic scenario is an extension of the second, and postulates that if we did encounter a vastly superior alien civilization, even if they were benevolent they could still do us harm through the simple stifling of human tendencies toward curiosity, ingenuity, and exploration. If suddenly an Encyclopedia Galactica was beamed down from the heavens, containing the accumulated knowledge and history of one or more billion-year-old cosmic civilizations, would people still strive to make new scientific discoveries and develop new technologies? Imagine if solutions were suddenly presented to us for all the greatest problems of philosophy, mathematics, physics, astronomy, chemistry, and biology. Imagine if ready-made technologies were suddenly made available that could cure most illnesses, provide practically limitless clean energy, manufacture nearly any consumer good at the press of a button, or rapidly, precisely alter the human body and mind in any way the user saw fit. Imagine not only our world or our solar system but our entire galaxy made suddenly devoid of unknown frontiers. Whatever would become of us in that strange new existence is something I cannot fathom.

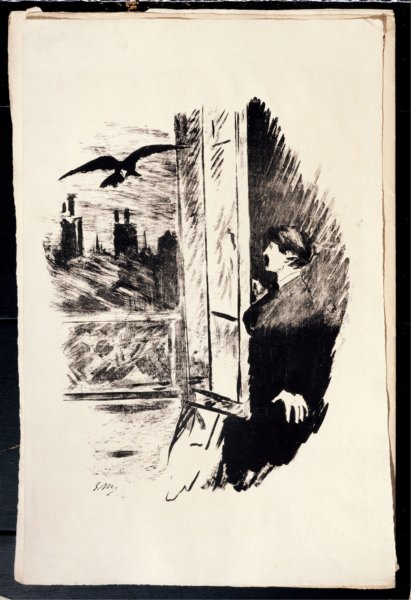

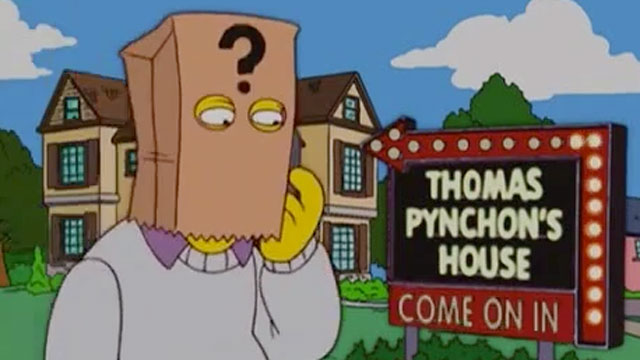

The late Czech astronomer Zdeněk Kopal summarized the pessimist outlook succinctly decades ago, in conversation with his British colleague David Whitehouse. As they were talking about contact with alien civilizations, Kopal grabbed Whitehouse by the arm and coldly said, “Should we ever hear the space-phone ringing, for God’s sake let us not answer. We must avoid attracting attention to ourselves.”•