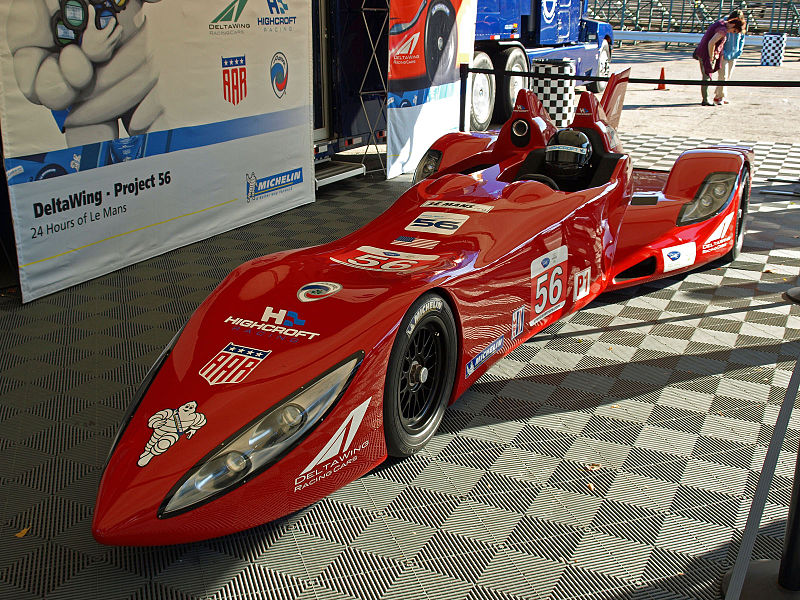

“A tiny triangular-shaped car known as the DeltaWing was giving the other 55 fire-breathing machines a run for their money.” (Image by Chris Pruitt.)

As science and technology continue to improve and carbon meets silicon with greater regularity, it’s increasingly difficult to assess the nature of so-called human competition. But even 40 years ago, the line was blurry. From the Economist, an article about cutting-edge auto engineering at the recent Le Mans:

“A tiny triangular-shaped car known as the DeltaWing was giving the other 55 fire-breathing machines a run for their money when it was unceremoniously bumped off the track and into the crash barrier by one of the Toyotas. So ended a brave attempt to show that a car with half the weight, half the horsepower and half the aerodynamic drag could run rings round the dreadnoughts of the sport.

It was not the first time that a radical, lightweight design has challenged conventional thinking in motor racing. Something similar happened when Colin Chapman’s featherweight Lotus 23, with Jim Clark at the wheel, made its debut at the Nürburgring’s infamous northern loop in 1962. With its tiny 100 horsepower motor (a third that of its rivals), the Lotus 23 shot ahead of the field of ponderous Porsches, Aston Martins and Ferraris. After one lap of the rain-soaked track, Clark was 27 seconds ahead of the leading Porsche driven by the American ace, Dan Gurney. The world of motor racing had never seen anything like it before.

The following month, when two Lotus 23 cars—one with a 750cc engine and the other with a 1,000cc unit—were entered for the Le Mans endurance race, French officials promptly banned them for being too good. Chapman swore never to enter a Lotus car for the 24-hour Le Mans race ever again—and kept his promise till the day he died.”

••••••••••

Jim Clark handling the Lotus 25, 1963:

Tags: Jim Clark