When Tina Brown was the Editor-in-Chief of the New Yorker, she would comment that “cuteness” was a factor in hiring writers. It seemed like more than a flippant remark. That was the world she wanted to inhabit, one in which appearance, in a number of ways, was preeminent. It’s a mindset that’s added little to the culture.

There were many changes the New Yorker needed to be make in 1992 when Brown was brought in to perform as a wrecking ball for the then-staid institution. Many of her reinventions weren’t the right ones, however. David Remnick often gives his predecessor credit for doing the heavy lifting in recreating the title, but female writers and editors (besides herself) were often pushed from the foreground on her watch. It’s only deep into Remnick’s reign that this egregious shift has been largely remedied. Hollywood and celebrity became central to the publication under Brown, and I will never forgive her for allowing Roseanne to guest edit an edition, the cheapest ploy in magazine’s history. (That’s no offense to Roseanne, who’s an excellent comic, but to the Editor-in-Chief who put her in that ridiculous position.) In addition to paring down the staff of scribes who’d ceased being useful, Brown also drove out many great and productive writers. The use of language in the New Yorker suffered under her tenure, though, to be fair, that was as much a problem of a troubled wider culture. It’s no shock Brown ended up in business with Harvey Weinstein—they were always on the same team.

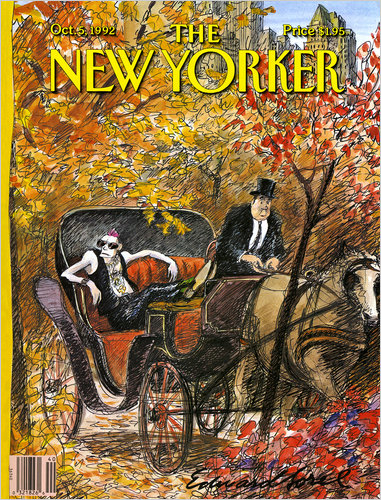

Funny that Brown’s first cover featured a punk. Her punk phase was as genuine as Ivanka Trump’s.

· · ·

In “A Likely Story,” Mimi Kramer’s Medium essay, the former New Yorker theater critic has crafted one of the most intelligent pieces on shitty men in media and elsewhere. In one section, she excoriates Brown, her former boss, with surgical precision. An excerpt:

There are — if I may be permitted to oversimplify wildly for a moment — two kinds of women in the working world who achieve great power. Those who are good at what they do and enjoy working with other smart or talented or thoughtful women. And there’s another kind that isn’t really good at much of anything at all but self-promotion, self-aggrandizement, and manipulating other people. That kind of woman will always enable and protect the Weinsteins of the world and encourage men in the demeaning of other women. There may be an element of self-loathing there, like the self-loathing Smith attributes to Weinstein himself; the women enablers may have some unconscious need to diminish and devalue something they lack.

There can be something almost sexy about working with gifted, brilliant people of either gender, whether you’re gay or straight. I remember once being stopped in the hallway by a veteran editor (she wasn’t even my editor) who had seen Bill Irwin’s The Regard of Flight, which I was writing about, and told me — with great tact and even more passion — that I’d left out the most important point about the show, how it was really all about race in America; and she was right. That was probably the most exciting moment in all my time at The New Yorker.

And I remember a story told me by Veronica, who was in on a few of Brown’s early editorial meetings. The question of how certain managerial roles would be meted out came up and someone brought up the name of the editor who had stopped me in the hall that time. Veronica told me that Brown quipped, “Oh, you mean the fat, homely girl with glasses,” and the men all laughed. Yes, they agreed, that was who was meant. Veronica pointed out that the woman under discussion was an accomplished poet and translator, and the men, chastened, all quickly agreed, “Yes, yes, very accomplished.

Tina Brown was the enabler-in-chief. It’s absurd for her to carry on as though she didn’t know of Weinstein’s depredations and wasn’t complicit. She’s the woman who put a young actress who wouldn’t sleep with Weinstein on the cover of the premiere issue of Talk dressed in S&M garb, crawling painfully toward the camera on her stomach like a submissive, and so generically made up as to render her unrecognizable as an individual. What the hell did she think that was saying?

It’s equally hard to stomach Brown on the subject of Weinstein’s grossness and unloveliness. Brown did more to vulgarize and uglify American letters than any other single person in America. She was the queen of the nothing-is-sacred mentality, establishing a redefinition of writing and journalism whereby nothing had any value at all but sex, shock, money, power, or celebrity.

She came to this country and, having failed to revive Vanity Fair, leaving it to a better editor and journalist to shape it into the very thing she’d hoped to achieve, went on to take a great literary institution — historic because it had introduced the vernacular into the American literary landscape, establishing that good writing could sound more like speech than like some gouty old Brit in a smoking jacket — and transformed it into something so crass you scarcely wanted to touch it, let alone look at or read it. (Actually, that last bit’s not me; it’s something I remember Louis Menand saying to me once.) This is a woman who thought declaring that The New Yorker would remain “text-driven” would reassure writers and journalists, who thought that putting topic-sentences at the top of every page of the magazine to make it easier to read was a good idea.

Brown’s performances on Charlie Rose and on BBC Newsnight offer up a demonstration of what she is very good at. She’s good at cant, and she’s good at a certain kind of corporate-political self-protection. It’s cunning, if mistaken, to try to get herself off the hook by blasting Donald Trump in the same breath as Harvey Weinstein. It’s enemy-of-my-enemy logic; she’s banking on the idea that Americans are too stupid to hold more than one idea in their heads at a time, hoping if she goes on record as a non-endorser of Trump, no one but Republicans will call her out on her hypocrisy. For her to get away with that would be more than a farce; it would be an obscenity. Not endorse Trump? She helped create the cesspool that made it possible for someone like Donald Trump to become the President of the United States. She’s part of the reason we’re in the mess we’re in now.•

Tags: Mimi Kramer