Since I was never a chess player, one of the things that surprised me when reading the long centerpiece of Garry Kasparov’s Deep Thinking, in which he recounted at length for the first time his two titanic battles in the 1990s with IBM’s Big Blue, was just how many seemingly obvious mistakes great human players make. I always assumed the best of the best went long flawless stretches before finally tripping up, but that’s not so. A game in which the two best players square off can see countless mistaken maneuvers—and that’s the case even if one of the competitors is a supercomputer.

In a smart New Standard interview conducted by Will Dunn, Kasparov compares his own humblings at the feet of technology to the lot of us potentially encountering an AI enhanced enough to remake society over the next several decades. He’s more sanguine than most when confronted by the specter of machine dominance, believing as industries fall before computers, others will rise to provide new employment, and that humans will succeed in what he terms “open systems.”

I think he’s making assumptions that may not prove true. Well-trained human telephone operators are to this point far better at handling caller queries than automated systems are, but that hasn’t stopped corporations from opting for the cheaper alternative. That doesn’t mean all jobs will disappear—though I bet lots of them in the medical field, including doctor, will be diminished—but it does mean that machines don’t necessarily have to be better to win, even outside of a closed system. Facebook and Google have all but proven that with their lackluster response to cyber espionage. And the more AI that slides into our lives, the more surveillance capitalism will become ubiquitous.

An excerpt:

By the mid-90s, Moore’s Law had held true for three decades. As in so many areas, the machines appeared to be little more than a novelty until, following the curve of exponential growth, their power became suddenly apparent. “The whole idea that if we had enough time, we would avoid making mistakes,” says Kasparov, “was ignorant. Humans are poised to make mistakes, even the best humans. And the whole story of human-machine competition is that the machines – first it’s impossible [that they could play], then the machines are laughably weak, then they are competing, for a brief time, and then, forever after, they are superior.”

But the inevitability of the machines’ success, says Kasparov, is not a matter of brute force, but of reliability. “Machines have a steady hand. It’s not that machines can solve the game” – the number of possible moves is so high that, even calculating at 200 million moves per second, it would have taken Deep Blue longer than the life of its opponent, or the solar system or quite possibly the universe itself, to calculate them all – “it’s about making moves that are of a higher average quality than humans.” The machine, says Kasparov, need never fear losing its concentration because it can never feel fear and it has no concentration to lose. “It doesn’t bother about making a mistake in the previous move. Humans are by definition emotional. Even the top experts, whether it be in chess, or video games, or science – we are prisoners of our emotions. That makes us easy prey for machines, in a closed system.”

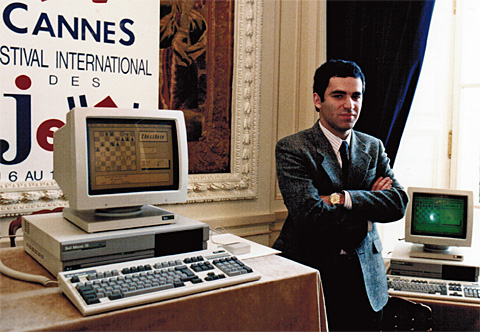

In 1997, Kasparov played his second match (he had won the first) against the IBM supercomputer Deep Blue and lost in the deciding game. He had been the World Champion since 1985, and would remain the world’s highest-rated human player until his retirement in 2005. He found losing to a machine to be “a shocking experience,” although this was partly, of course, because “I haven’t lost many games… Now, two decades later, I realise it was a natural process.”

But Kasparov does not think humans are about to be replaced entirely by machines. Even in cyber security, where automation and machine learning are necessary, “It’s not a closed system, because there are no written rules. Actually, it’s one of the areas where human-machine collaboration will have a decisive effect. I think it’s naïve to assume that machines could be totally dominant, because the angle of attack can change. There are so many things that can change. It’s an unlimited combination of patterns that can be manipulated.”•

__________________________

“It was very easy, all the machines are only cables and bulbs.”

Tags: Garry Kasparov, Will Dunn