Donald Trump will end in disgrace, not primarily because he’s an ignorant con artist wholly unfit to be President, but because he has stashed in his closet a mausoleum full of skeletons pertaining to his personal life, business career and Russia. His family’s laundry is dirty despite all the laundering he’s done. Trump ultimately falls, as do his cohort of disgraceful henchmen, half-wits and horseshitters. This sordid episode doesn’t conclude in book deals all around but in most of the players being booked.

That won’t, however, save America. Our problems run deeper and wider than Trump, who’s the culmination of our social collapse, not the source. Russia’s machinations and James Comey’s boneheaded move may have put the QVC quisling over the top, but there’s really no rationalizing nearly 63 million citizens pulling the lever for a completely unqualified and indecent anti-politician. We’ve been heading for this disaster for generations, our break from reality a long time coming.

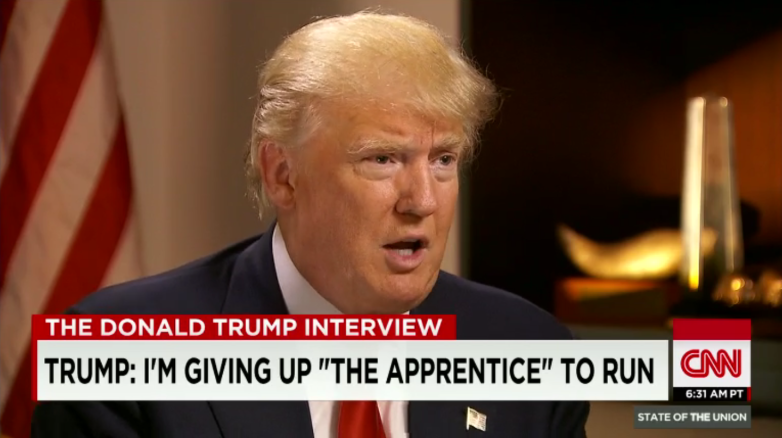

In an excellent Atlantic essay, Kurt Andersen, who has a history with Trump, writes that he began to notice our ugly divorce from reality during the Dubya Era “truthiness,” precisely in 2004. It’s interesting the writer chose the year he did, because that was when The Apprentice debuted, and a deeply immoral and largely failed businessman was awarded the role of Manhattan’s greatest builder despite not being able to get a loan of clean money to open a tent in Central Park.

But our fall from grace has more distant origins. Our drift started with Reagan unwinding the Fairness Doctrine, the rise of cable news, the emergence of Reality TV and the decentralization of the media, when the gatekeepers of legacy journalism were obliterated, when anyone could suddenly pose as an expert on vaccinations or trade pacts. The Internet made it possible to legitimize our most dubious fears and worst impulses.

We have more information than ever before, and it’s been put to worrisome use, as “lone gunmen” and multi-billion dollar corporations alike began to commodify conspiracy theories, from Ancient Aliens to Pizzagate to Seth Rich. The sideshow that has always existed in the U.S. was relocated to the center ring, as Chuck Barris’ suspicion about America’s dark side proved truer than even he could have predicted.

As much as anything, performance became essential to success, convincingly playing a Doctor, Survivor or a populist Presidential candidate was more important than truth. Life became neither quite real nor fake, just a sort of purgatory. It’s a variation of who we actually are–a vulgarization.

· · ·

It’s a new abnormal that’s been creeping over this relatively wealthy though often dissatisfied nation for decades. Here’s the transcript of a scene from 1981’s My Dinner with Andre, in which Wallace Shawn and Andre Gregory discuss how performance had become introduced in a significant way into quotidian life, and that was way before Facebook gave the word “friends” scare quotes and prior to Kardashians, online identities and selfies:

Andre Gregory:

That was one of the reasons why Grotowski gave up the theater. He just felt that people in their lives now were performing so well, that performing in the theater was sort of superfluous, and in a way, obscene. Isn’t it amazing how often a doctor will live up to our expectation of how a doctor should look? You see a terrorist on television and he looks just like a terrorist. I mean, we live in a world in which fathers, single people or artists kind of live up to someone’s fantasy of how a father or single person or an artist should look and behave. They all act like that know exactly how they ought to conduct themselves at every single moment, and they all seem totally self-confident. But privately people are very mixed up about themselves. They don’t know what they should be doing with their lives. They’re reading all these self-help books.

Wallace Shawn:

God, I mean those books are so touching because they show how desperately curious we all are to know how all the others of us are really getting on in life, even though by performing all these roles in life we’re just hiding the reality of ourselves from everybody else. I mean, we live in such ludicrous ignorance of each other. I mean, we usually don’t know the things we’d like to know even about our supposedly closest friends. I mean, I mean, suppose you’re going through some kind of hell in your own life, well, you would love to know if your friends have experienced similar things, but we just don’t dare to ask each other.

Andre Gregory:

No, it would be like asking your friend to drop his role.

Wallace Shawn:

I mean, we just put no value at all on perceiving reality. On the contrary, this incredible emphasis we now put on our careers automatically makes perceiving reality a very low priority, because if your life is organized around trying to be successful in a career, well, it just doesn’t matter what you perceive or what you experience. You can really sort of shut your mind off for years ahead in a way. You can turn on the automatic pilot.•

· · ·

The opening of Andersen’s article, in which he argues that Sixties individualism and Digital Age fantasy conspired to lay us low:

When did America become untethered from reality?

I first noticed our national lurch toward fantasy in 2004, after President George W. Bush’s political mastermind, Karl Rove, came up with the remarkable phrase reality-based community. People in “the reality-based community,” he told a reporter, “believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality … That’s not the way the world really works anymore.” A year later, The Colbert Report went on the air. In the first few minutes of the first episode, Stephen Colbert, playing his right-wing-populist commentator character, performed a feature called “The Word.” His first selection: truthiness. “Now, I’m sure some of the ‘word police,’ the ‘wordinistas’ over at Webster’s, are gonna say, ‘Hey, that’s not a word!’ Well, anybody who knows me knows that I’m no fan of dictionaries or reference books. They’re elitist. Constantly telling us what is or isn’t true. Or what did or didn’t happen. Who’s Britannica to tell me the Panama Canal was finished in 1914? If I wanna say it happened in 1941, that’s my right. I don’t trust books—they’re all fact, no heart … Face it, folks, we are a divided nation … divided between those who think with their head and those who know with their heart … Because that’s where the truth comes from, ladies and gentlemen—the gut.”

Whoa, yes, I thought: exactly. America had changed since I was young, when truthiness and reality-based community wouldn’t have made any sense as jokes. For all the fun, and all the many salutary effects of the 1960s—the main decade of my childhood—I saw that those years had also been the big-bang moment for truthiness. And if the ’60s amounted to a national nervous breakdown, we are probably mistaken to consider ourselves over it.

Each of us is on a spectrum somewhere between the poles of rational and irrational. We all have hunches we can’t prove and superstitions that make no sense. Some of my best friends are very religious, and others believe in dubious conspiracy theories. What’s problematic is going overboard—letting the subjective entirely override the objective; thinking and acting as if opinions and feelings are just as true as facts. The American experiment, the original embodiment of the great Enlightenment idea of intellectual freedom, whereby every individual is welcome to believe anything she wishes, has metastasized out of control. From the start, our ultra-individualism was attached to epic dreams, sometimes epic fantasies—every American one of God’s chosen people building a custom-made utopia, all of us free to reinvent ourselves by imagination and will. In America nowadays, those more exciting parts of the Enlightenment idea have swamped the sober, rational, empirical parts. Little by little for centuries, then more and more and faster and faster during the past half century, we Americans have given ourselves over to all kinds of magical thinking, anything-goes relativism, and belief in fanciful explanation—small and large fantasies that console or thrill or terrify us. And most of us haven’t realized how far-reaching our strange new normal has become.•

Tags: Kurt Andersen