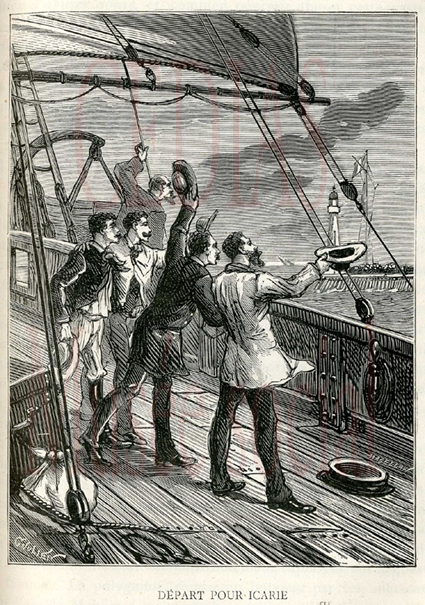

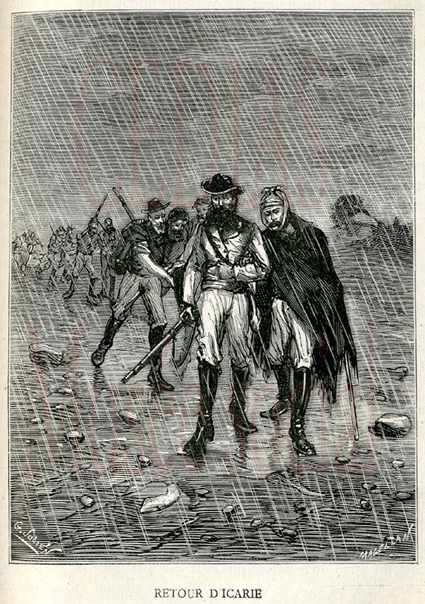

Was recently reading something about the Icarians, the French Utopian socialist sect based on the teachings of Étienne Cabet, which left small footprints on U.S. soil during the “stammering century.” The members first immigrated to America in 1848, purchasing small parcels in Illinois, Iowa, Missouri, California and, very disastrously, in Texas, on which to build their communities based on “technological innovation.”

Was recently reading something about the Icarians, the French Utopian socialist sect based on the teachings of Étienne Cabet, which left small footprints on U.S. soil during the “stammering century.” The members first immigrated to America in 1848, purchasing small parcels in Illinois, Iowa, Missouri, California and, very disastrously, in Texas, on which to build their communities based on “technological innovation.”

In a 2016 New Republic article by Chris Jennings about the Lone Star State debacle, he describes the tenets of the group put forth in the Cabet novel Voyage en Icarie:

In Icaria, there is no private property or money. Food, shelter, clothing, and all of life’s comforts are produced and distributed by the state. Men and women are considered equal and receive the same comprehensive public education, although women do not vote. When an Icarian family runs low on food, they place a specially designed container into a specially designed niche outside of their specially designed apartment. When they return home after a day working in collective workshops, they find their bin topped off with healthful victuals. The sources of Icarian abundance are technological innovation and the fact that everyone works for the wealth of the republic. There are no idle rich or landed aristocracy to draw off the wealth of the nation. As a result of these reforms, many old occupations have been rendered obsolete. In Icaria there are no domestic servants, cops, informants, middlemen, soldiers, gunsmiths, or bankers.

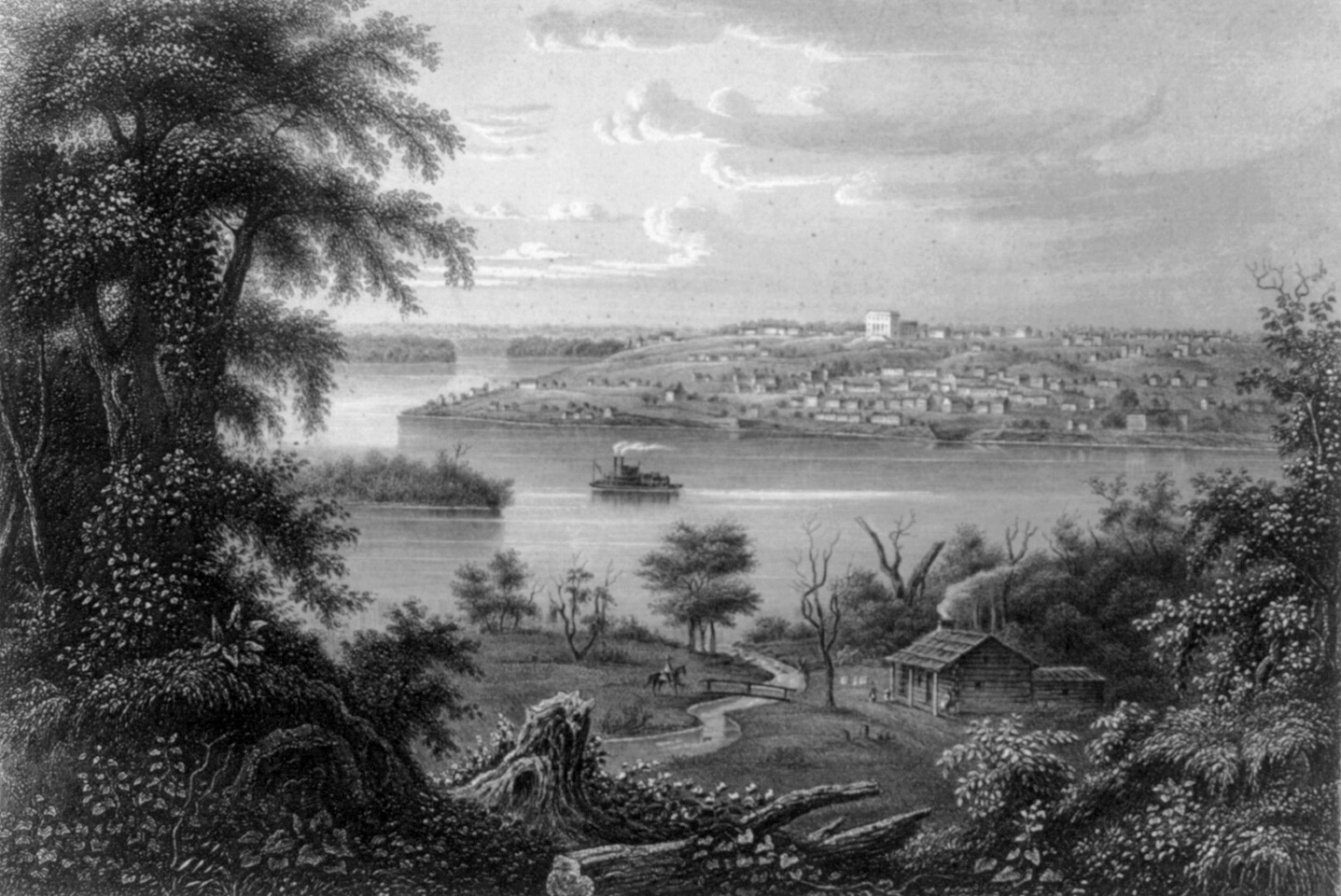

Even if the Icarians had be experienced homesteaders rather than urban ideologues, it wasn’t perhaps the most propitious moment to establish an alternative colony in America, with Mormons, for instance, on numerous occasions having their towns razed to the ground. In fact, the first permanent Icarian settlement was founded in Nauvoo, Illinois, on the literal ruins of a Mormon community.

Despite sometimes unwittingly purchasing unfortunate tracts and meeting with withering stares, the Icarians were particularly persistent, with the group often splintering, but surviving in some form, until nearly the fin de siècle era.

From the July 30, 1853 Brooklyn Daily Eagle: