In Disturbing the Universe, Freeman Dyson wrote this of his friend Richard Feynman, who graduated with honors from Los Alamos but forever felt saddled by the “student debt”:

He thought that wars would continue to occur from time to time, and that nuclear weapons would be used. He felt that we were fools to think that we deserved to get away scot-free after letting these weapons loose in the world. He expected that somebody would sooner or later come back to give us a taste of our own medicine. He saw no reason to believe that other countries would be wiser or kinder than we had been. He found it amazing that people would go on living calmly in places like New York as if Hiroshima had never happened.

To briefly answer his curiosity, people continue to live in places like NYC (or San Fran or L.A.) despite the exorbitant cost and numerous other burdens–yes, including the threat of being nuked–mostly because they’re fun and interesting places and life is short.

That said, I’ve always been spooked by the physicist’s comments about New York and nuclear bombs in the 1981 documentary The Pleasure of Finding Things Out. In one scene, Feynman discusses his role as a Ph.D. candidate working, beginning in 1943, for the Manhattan Project, a job he viewed at first as burden, then duty, then fun, then burden all over again. He was a deeply moral man who believed in retrospect that he hadn’t ultimately acted with much depth or morality, very troubled that he continued to work on the mission even after Germany surrendered. Feynman’s words:

It was a completely different kind of a thing. It would mean that I would have to stop the research in what I was doing, which was my life’s desire, to do this, which I felt I should do to protect civilization, if you want, okay? So that was what I had to debate with myself. My first reaction was that I didn’t want to get interrupted from my normal work to do this odd job. There was also the problem–of course, any moral thing involving war I didn’t want much to do about that. It kind of scared me when I realized what the weapon would be, and that since it might be possible, there was nothing that indicated that if we could do it that they couldn’t do it, therefore it was very important to try to cooperate.

With regard to moral questions, I do have something I would like to say about it, because the original reason to start the project, which I had, was that the Germans were a danger, which started me off on a process of action which was to be the first to develop this system at Princeton and then at Los Alamos, to try make the bomb work, all kinds of attempts at redesign to make it a worse bomb or whatever, and so on…and all of us working at this time to see if we could make it go. And so it was a project on which we all worked very, very hard and all cooperating together. With any project like that you continue to work to try to get success, having decided to do it. But what I did immorally, I would say, was not to remember the reason I said I was doing it, so that when the reason changed, which was that Germany was defeated, not the single thought came to my mind at all about that–that that meant that I had to reconsider doing this. I simply didn’t think, okay?

Only reaction I had, maybe I was blinded by my own reaction, was a very considerable elation and excitement. There were parties, and people got drunk, and it would make a tremendously interesting contrast of what was going on in Los Alamos as the same time as what was going on in Hiroshima. I was involved with this happy thing and also drinking, drunk, playing drums sitting on the hood–a bonnet–of a jeep, and playing drums, excitement running all over Los Alamos, at the same time as the people were dying and struggling at Hiroshima.

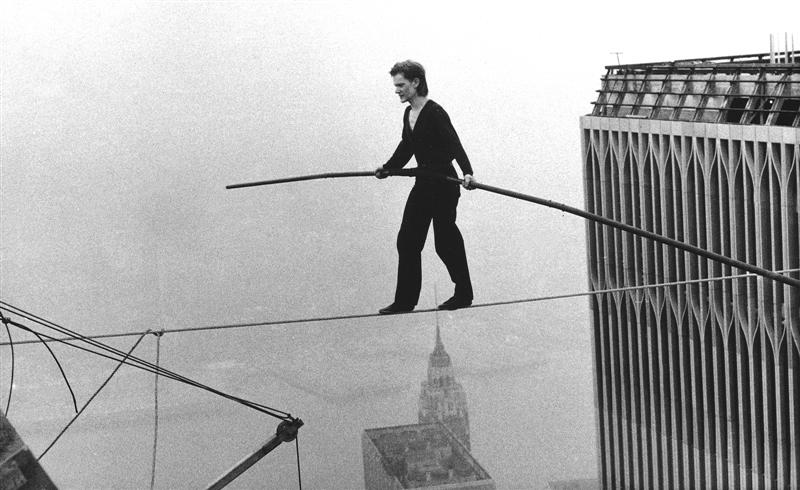

I had a very strong reaction after the war of a peculiar nature…it may be just from the bomb itself or it may be from some other psychological reasons, I had just lost my wife or something. But I remember being in New York with my mother in a restaurant right after, immediately after, and thinking about New York, and I knew how big the bomb in Hiroshima was, how big an area it covered, and so on, and I realized from where we were–I don’t know, 59th Street–to drop one at 34th Street, and that would spread all the way out and all these people would be killed and all these things would be killed, and that wasn’t the only one bomb available but it was easy to continue to make them and therefore that things were sort of doomed, because already it appeared to me, earlier than to others who were more optimistic, that international relations and the way people were behaving was no different than it had ever been before, and that it was just going to go out the same way as any other thing, and I was sure it was going to be therefore used very soon. So, I felt very uncomfortable and I thought, really believed, that it was silly…I would see people building a bridge and I would say, “They don’t understand.” I really believed that it was senseless to make anything because it would all be destroyed anyway soon, that they didn’t understand that, and I had this very strange view of any construction I would see. I always thought, How foolish they are to try to make something. So I was really in a kind of depressive condition.•