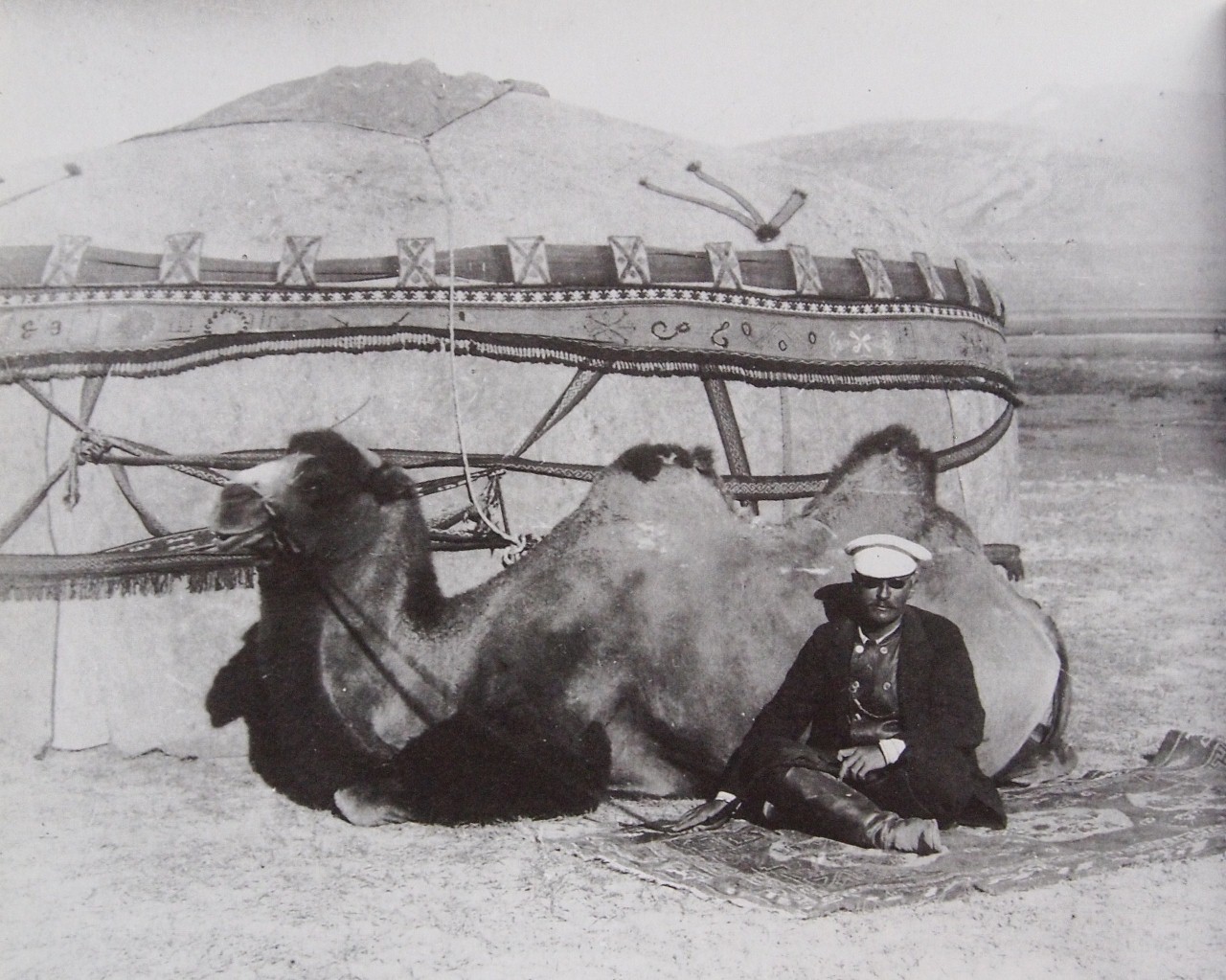

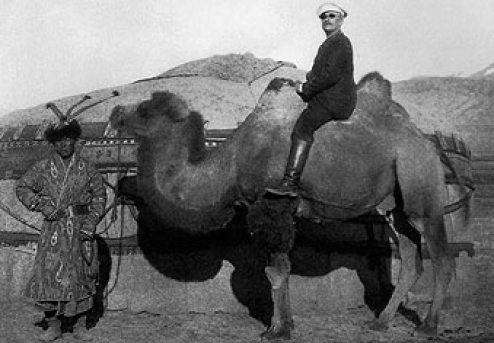

Much of Sven Hedin’s life was lived in public, but the truth about him is somewhat buried nonetheless, strange for a Swedish explorer who spent his life unearthing the hidden. His expeditions to Central Asia just before and after beginning of the twentieth century introduced the world to invaluable art and artifacts and folkways and cities that had been lost to time.

Hedin was admired for these efforts in all corners of the world, including the one occupied by Adolf Hitler. The geographer perplexingly returned the Führer’s admiration, believing in the Nazi leader’s nationalistic and traditionalist tendencies, which was obviously a catastrophic misjudgement. He was highly critical, however, of the Party’s anti-Semitism.

These protests brought trouble. Hitler seems to have blackmailed the famed explorer into publishing pro-Nazi tracts by imperiling some of Hedin’s Jewish friends still inside Germany. But it’s difficult to accept that Hedin encouraged Sweden to ally with Germany during WWII to save a few friends or even that he truly believed he could somehow compartmentalize various aspects of the uniformly deviant Third Reich. He just apparently didn’t want to recognize the evil. A disease of the eye caused Hedin to become partially blind in 1940, an apt metaphor for this period of his life.

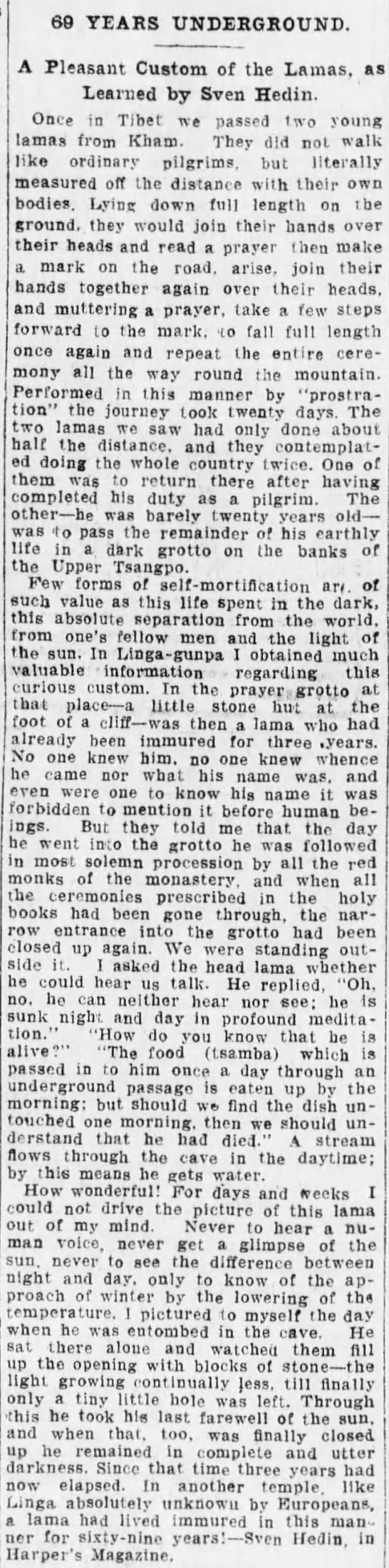

Long before his political descent, Hedin penned an article for Harper’s about an unusual Tibetan custom in which monks passed their lives in subterranean isolation, a piece reprinted in the September 17, 1908 Brooklyn Daily Eagle.