I find myself thinking often of a passage from the opening chapter of Ian Frazier’s excellent 2000 book, On the Rez. In telling about Chief Red Cloud’s visit to the White House in 1870, Frazier examined our age and came to some troubling conclusions, all of which seem even truer 16 years on. Real freedom in our corporatocracy is more expensive than ever, but it’s cheap and easy to be discarded. The excerpt:

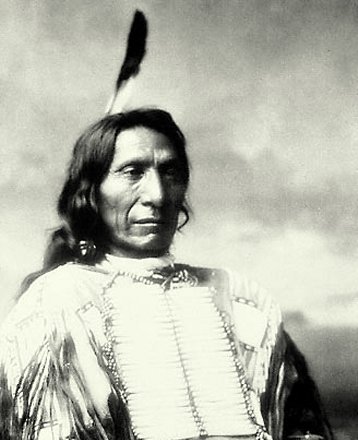

In 1608, the newly arrived Englishmen at Jamestown colony in Virginia proposed to give the most powerful Indian in the vicinity, Chief Powhatan, a crown. Their idea was to coronate him a sub-emperor of Indians, and vassal to the English King. Powhatan found the offer insulting. “I also am a King,” he said, “and this is my land.” Joseph Brant, a Mohawk of the Iroquois Confederacy between eastern New York and the Great Lakes, was received as a celebrity when he went to England with a delegation from his tribe in 1785. Taken to St. James’s Palace for a royal audience, he refused to kneel and kiss the hand of George III; he told the King that he would, however, gladly kiss the hand of the Queen. Almost a century later, the U.S. government gave Red Cloud, victorious war leader of the Oglala, the fanciest reception it knew how, with a dinner party at the White House featuring lighted chandeliers and wine and a dessert of strawberries and ice cream. The next day Red Cloud parleyed with the government officials just as he was accustomed to on the prairie—sitting on the floor. To a member of a Senate select committee who had delivered a tirade against Sitting Bull, the Hunkpapa Sioux leader carelessly replied, “I have grown to be a very independent man, and consider myself a very great man.”

That self-possessed sense of freedom is closer to what I want; I want to be an uncaught Indian like them.

Another remark which non-Indians often make on the subject of Indians is “Why can’t they get with the program?” Anyone who talks about Indians in public will be asked that question, or variations on it; over and over: Why don’t Indians forget all this tribal nonsense and become ordinary Americans like the rest of us? Why do they insist on living in the past? Why don’t they accept the fact that we won and they lost? Why won’t they stop, finally, being Indians and join the modern world? I have a variety of answers handy. Sometimes I say that in former days “the program” called for the eradication of Indian languages, and children in Indian boarding schools were beaten for speaking them and forced to speak English, so they would fit in; time passed, cultural fashions changed, and Hollywood made a feature film about Indians in which for the sake of authenticity the Sioux characters spoke Sioux (with English subtitles), and the movie became a hit, and lots of people decided they wanted to learn Sioux, and those who still knew the language, those who had somehow managed to avoid “the program” in the first place, were suddenly the ones in demand. Now, I think it’s better not to answer the question but to ask a question in return: What program, exactly, do you have in mind?

We live in a craven time. I am not the first to point out that capitalism, having defeated Communism, now seems to be about to do the same to democracy. The market is doing splendidly, yet we are not, somehow. Americans today no longer work mostly in manufacturing or agriculture but in the newly risen service economy. That means that most of us make our living by being nice. And if we can’t be nice, we’d better at least be neutral. In the service economy, anyone who sat where he pleased in the presence of power or who expatiated on his own greatness would soon be out the door. “Who does he think he is?” is how the dismissal is usually framed. The dream of many of us is that someday we might miraculously have enough money that we could quit being nice, and everybody would then have to be nice to us, and niceness would surround us like a warm dome. Certain speeches we would love to make accompany this dream, glorious, blistering tellings-off of those to whom we usually hold our tongue. The eleven people who actually have enough money to do that are icons to us. What we read in newsprint and see on television always reminds us how great they are, and we can’t disagree. Unlike the rest of us, they can deliver those speeches with no fear. The freedom that inhered in Powhatan, that Red Cloud carried with him from the plains to Washington as easily as air—freedom to be and to say, whenever, regardless of disapproval—has become a luxury most of us can’t afford.•