Buckminster Fuller was right on some vital points even if most of his designs never made a leap from the drawing board. He knew, for instance, that the idea of race was a phony tribal concept steeped in ignorance, wealth inequality was a real threat to democracy and childbirth per family would decline as the infant mortality rate decreased.

The theorist, who certainly realized the delicate balance of our environment, may or may not have been right when he insisted pollution itself was a great resource gone unharvested, a recyclable more or less, but that’s an awfully dangerous assumption. Even if it’s so, our “creation” of these raw materials could extinct the species long before we establish a collection day. Technocracy has its merits, but I wouldn’t want to wager everything on it.

In a smart Aeon essay, Samanth Subramanian wonders about the renewed capital of Fuller’s teachings in this time of climate peril and technological prowess, when those domes Elon Musk dreams of printing on Mars may soon be as needed on Earth. The opening has a great, largely forgotten anecdote about a Vermont town deciding in 1979 to build a Fuller-ish dome around itself to deal with falling temperatures and rising gas prices, before quickly quashing the project. The writer also de-mythologizes much about the Futurist, whose self-promoting prowess was Jobsian long before Jobs was born.

An excerpt:

Fuller wasn’t the first person to dream of domed cities – they’d featured for decades in science fiction, usually as hothouses of dystopia – but as an engineering solution, they feel thoroughly Fullerian. Implicit in their concept is an acknowledgement that human nature is wasteful and unreliable, resistant to fixing itself. Instead, Fuller put his faith in technology as a means to tame the messiness of humankind. ‘I would never try to reform man – that’s much too difficult,’ Fuller told The New Yorker in 1966. Appealing to people to remedy their behaviour was a folly, because they’d simply never do it. Far wiser, Fuller thought, to build technology that circumvents the flaws in human behaviour – that is, ‘to modify the environment in such a way as to get man moving in preferred directions’. Instead of human-led design, he sought design-led humans.

Winooski’s grand dome never went into construction. By the end of 1980, after the election of Ronald Reagan as president and a summer of stormy criticism over the cost and visual impact of the project, the mood had shifted. But Fuller, who had first advanced the idea of a domed city in 1959, continued to champion it until his death in 1983. ‘The way consumption curves are going in many of our big cities, it is clear that we are running out of energy,’ he wrote. ‘It is important for our government to know if there are better ways of enclosing space in terms of material, time, and energy.’ The most ambitious of his urban lids was the dome he wanted to lower over midtown Manhattan, a mile high and two miles in diameter. As well as a perfect climate, Fuller said, the dome could protect New Yorkers against the worst effects of a nuclear bomb going off nearby.

In the great flux of postwar United States, Fuller was convinced that the world was marshalling its resources poorly and unsustainably, and that change was a burning imperative. The world finds itself again passing through a Fullerian moment – a phase of political, environmental and technological upheaval that is both unsettling and exhilarating. Within this frame, Fuller’s life and ideas – the sound ones but also those that were tedious or absurd – ring with a new resonance.•

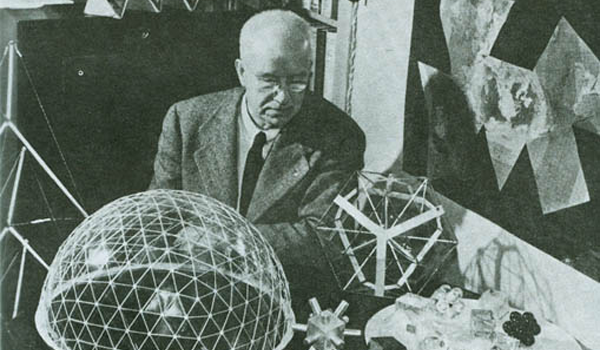

Fuller introduces the Dymaxion House in 1929.