When I first became aware of Chuck Close’s portraiture, long before his artistic and personal metamorphosis, the work immediately seemed to me pointillism for the computer age, his very human hand–seriously compromised following a massive seizure–somehow capable of producing pixels.

As amazing as Close’s parade of faces are, it would be different, even troubling, for some if they’d been painted with a computer rather than a brush attached to flesh. They might be viewed as inferior even if the pictures looked exactly the same. That’s because we tend to value the skills we know more than emergent ones.

In “There Is No Difference Between Computer Art and Human Art,” a provocative Aeon essay, Oliver Roeder argues for the erasure of the line between algorithms making art and music and people doing so. He writes: “‘Computer art’ doesn’t really exist in an any more provocative sense than ‘paint art’ or ‘piano art’ does. The algorithmic software was written by a human, after all, using theories thought up by a human.”

Well there is some difference between the two, as there is between oral histories and those published by a printing press. That doesn’t mean the work with a digital tool attached is lesser, however. It can be greater.

An excerpt:

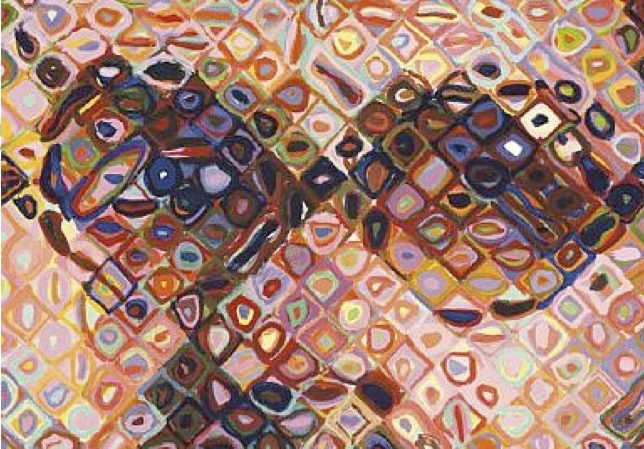

Visual art, too, has been subjected to algorithms for decades now.Two engineers created this image – probably the first computer nude – at Bell Labs in Murray Hill, New Jersey, somewhere geographically between Coltrane and Kim, in 1966. The piece was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in 1968.

The New York Times reviewed one of the first exhibitions of computer art, in 1965 (just a few months after Coltrane’s recording session) featuring work by two scientists and an IBM #7094 digital computer, at a New York gallery, now long shuttered. ‘So far the means are of greater interest than the end,’ the Times wrote. But the review, by the late Stuart Preston, goes on to strike a surprisingly enthusiastic tone:

No matter what the future holds – and scientists predict a time when almost any kind of painting can be computer-generated – the actual touch of the artist will no longer play any part in the making of a work of art. When that day comes, the artist’s role will consist of mathematically formulating, by arranging an array of points in groups, a desired pattern. From then on, all will be entrusted to the deus ex machina. Freed from the tedium of technique and the mechanics of picture-making, the artist will simply ‘create’.

The machine is just the brush – a human holds it. There are, indeed, examples of computers helping musicians to simply ‘create’.•

Tags: Oliver Roeder, Stuart Preston