America is doing really well, in the aggregate.

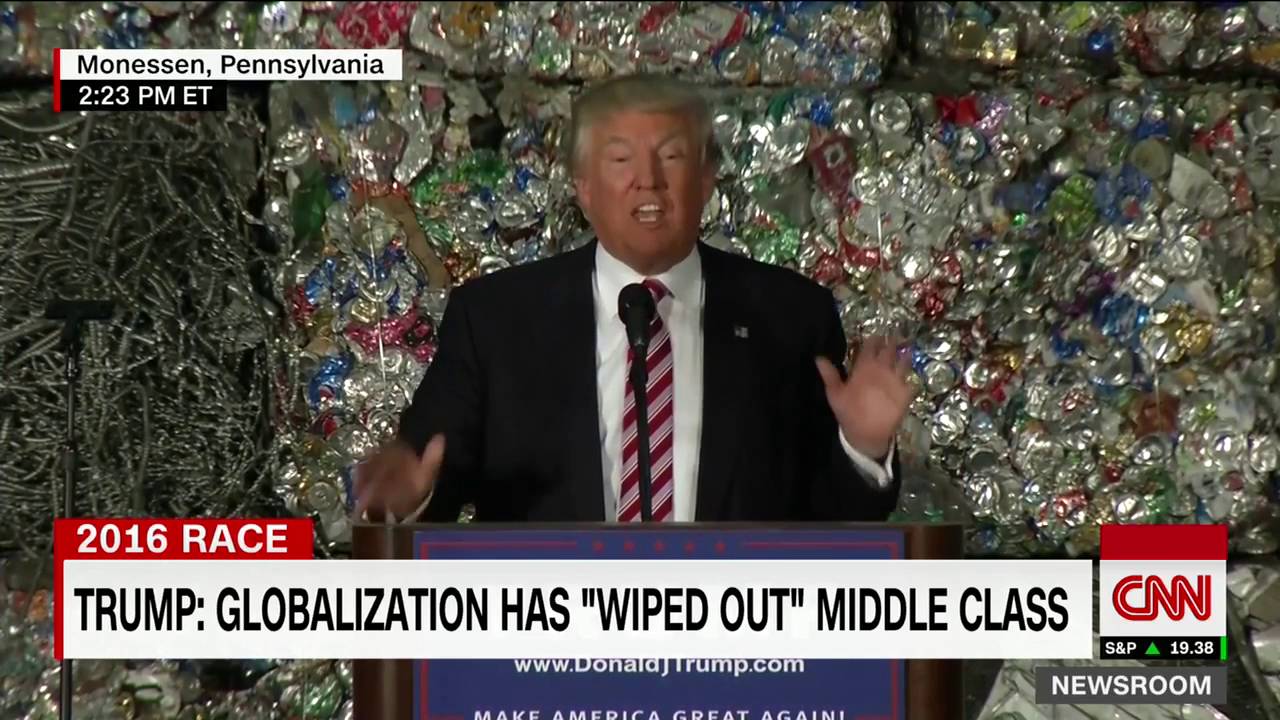

A closer look at the numbers reveals our prosperity has grown increasingly top-heavy for decades, a failure that’s not an orphan. Among the factors suppressing the earnings of the vast majority are tax codes, the decline of unions, corporate pay structures, globalization and automation.

The future looks bright in the big picture, but only if we find a way to allow working-class people to participate in the wealth created. Otherwise we’ll develop a large underclass distracted intermittently by the few amazing, cheap gadgets in their pockets, by bread and Kardashians.

Investment in workers and infrastructure is key, as always. It’s worth noting that if too many jobs are automated out of existence too quickly, we may have a challenge that even education can’t remedy.

From Edward Alden and Rebecca Strauss’ smart Foreign Affairs article, “Is America Great?“:

In our own research, we have looked in detail at how the United States measures against other advanced economies on many of the attributes that underlie national competitiveness, from innovation to education. The picture is a pretty good one. On innovation, for example, which drives economic growth in wealthy nations, the United States is far ahead of any country in the world. Corporate taxes and regulations, although both in real need of reform and modernization, do not pose the serious competitive disadvantage that many Republicans have suggested. The United States has slipped in global education rankings, but there are encouraging signs of progress, with high school graduation rates recently reaching record levels.

So if the United States is doing so well compared to its economic rivals, what accounts for the political appeal of claims that it has been a loser in global competition? The answer lies in the growing disconnect between the macro-level performance of the U.S. economy, which has been reasonably good, and the economy as it is lived by many Americans, which has been far from good.

The economist Michael Porter and his colleagues at Harvard Business School have called it “an economy doing only half its job.” Porter defines a competitive economy as one in which companies can compete successfully in global markets while also supporting rising wages and living standards for ordinary citizens. U.S. companies such as Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google account more than half of the top 100 companies in the world by market value, and such firms have only gained ground over the past five years. But despite this competitive triumph, wages and living standards for the average American have stagnated for decades. Real wages have been flat since the 1970s, which roughly corresponds with the time when the United States began facing tougher overseas competition, first from Japan and Germany and later from China. Young men today, who have been hit particularly by the disappearance of manufacturing jobs, on average earn less than their fathers did.

Porter and his colleagues argue that the biggest cause of this growing divide is the failure of governments, and of companies themselves, to invest in Americans—to give them the education, skills, infrastructure, and access to capital they to need to prosper along with U.S. companies.•

Tags: Edward Alden, Rebecca Strauss