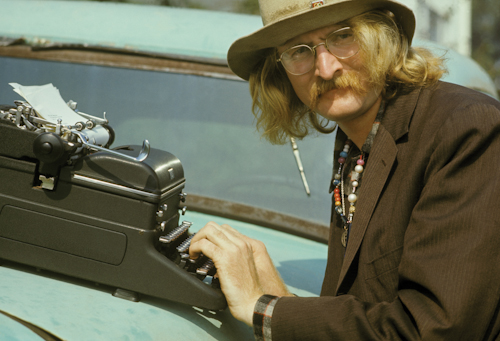

A miscast spokesperson of drugged-out hippies, the writer Richard Brautigan wasn’t enamored with narcotics nor the wide-eyed, bell-bottomed set. He wrote two things I love: The 1967 novel Trout Fishing in America and the 1968 poem “All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace.”

What follows is an excerpt from Lawrence Wright’s 1985 Rolling Stone article about Brautigan’s death and a German TV interview conducted a year before his passing. In the latter, he says this: “I think perception is one of the incredible qualities of human beings, and anyway that we can expand or define or redefine or adventure into the future of perception, we should use whatever means to do so.”

From Wright:

His passions were basketball, the Civil War, Frank Lloyd Wright, Southern women writers, soap operas, the National Enquirer, chicken-fried steak and talking on the telephone. Wherever he was in the world, he would phone up his friends and talk for hours, sometimes reading them an entire book manuscript on a transpacific call. Time meant nothing to him, for he was a hopeless insomniac. Most of his friends dreaded it when Richard started reading his latest work to them, because he could not abide criticism of any sort. He had a dead ear for music. [His daughter] Ianthe remembered that he used to buy record albums because of the girls on the covers. He loved to take walks, but he loathed exercise in any other form.

The fact that Richard couldn’t drive allowed him to build up an entourage of chauffeurs wherever he went. For many of them, it was an honor, and they didn’t mind that it was calculated dependency on Richard’s part.

Richard had wild notions about money. Although he was absurdly parsimonious, sometimes demanding a receipt for a purchase of bubblegum, he was also a heavy tipper, handing out fifty-dollar tips for five-dollar cab fares. He liked to give the impression that money was meaningless to him. The floor of his apartment was littered with spare change, like the bottom of a wishing well, and he always kept his bills wadded up in his pants pockets, but he knew to the dime how much money he was carrying. He was famously openhanded, but when he had to borrow money from his friends, he was slow paying it back. He often tried to pay them in “trout money,” little scraps of paper on which he had scrawled an image of a fish. He had the idea that they would be wildly valuable, because they had been signed by Richard Brautigan. At least, that’s what he told his creditors.

Christmas was a special problem for him. His friends were horrified that Richard liked to spend his Christmases in porno theaters. They decided it must have something to do with his childhood. Richard was mum on the subject. Ron Loewinsohn remembered when Richard came to read at Harvard. Yes, Richard was famous, a spokesman for his generation, but he was also a kind of bumpkin, half-educated, untraveled, a true provincial. He had never been East. He wanted to be taken seriously, of course, but he was suspicious and a little afraid of academicians — including Ron, who was in graduate school at Harvard when Richard arrived. Life magazine came along, and there was even a parade down Massachusetts Avenue, with a giant papier-mâché trout in the lead. After the reading, Ron and Richard went to Walden Pond, and as they walked along the littered banks of Thoreau’s wilderness, the photographer walked backward in front of them, snapping away. It was strange to be linked in this media ceremony to the two American writers who had most influenced Richard — Thoreau, who was like Richard at least in his solitariness and his love of nature, and Hemingway, who had also received the star treatment from Life.

In 1970, when Richard was still tremendously popular, he confided to Margot Patterson Doss, the San Francisco Chronicle columnist, that he had never had a birthday party. She let him plan one for himself at her house. He decorated the house with fish drawings — “shoals of them,” Margot said — and when she asked whom he wanted to cater the affair, he picked Kentucky Fried Chicken. Everyone came — Gary Snyder, Robert Duncan, Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, Phil Whalen, many of the finest poets of the era — all honoring Richard. When it came time to blow out the candles on the cake, Richard refused. “This is the Age of Aquarius,” he said. “The candles will blow themselves out.” He was thirty-five.•

The German TV interview.