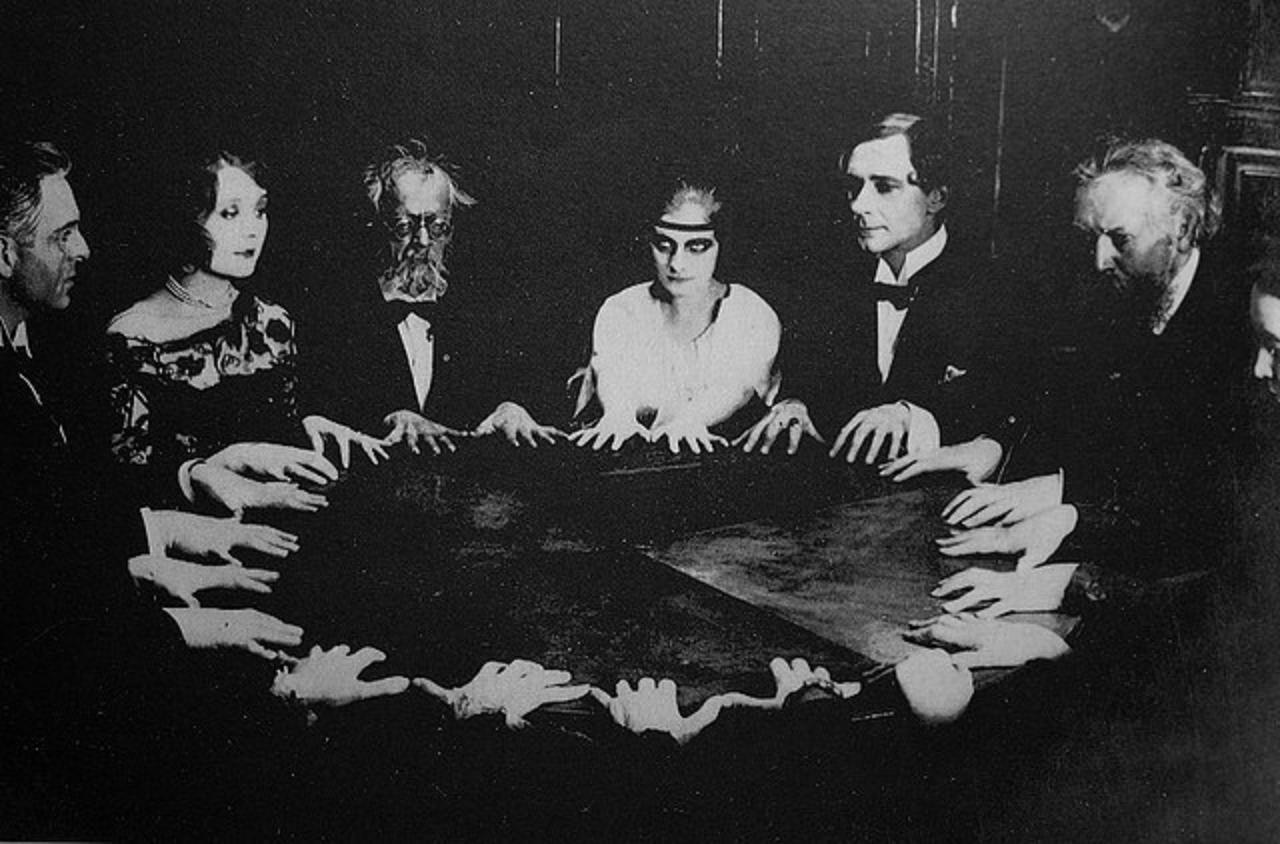

When my brother died last year, he remained in the ether. A devoted Facebook user, his likes and friends were gathered conveniently in one space, and the updates and comments keep coming even though he’s no longer here to read, or respond to, them. This Digital Age seance bothers me. It seems an odd and unsatisfactory afterlife of sorts.

That’s my own problem, however. He would have loved receiving messages on birthdays and holidays, even after he was gone. The question is this: If I knew my own end was approaching and I was the last relative alive who knew him, would I delete his account or let it “live on,” whatever that may come to mean? I’m pretty sure I would choose the latter.

In a BBC Future piece, Brandon Ambrosino writes about this social-media phenomenon, in which Facebook serves as not only a virtual city-state but also a necropolis, impacting the way we mourn, remember and forget. Someday, if the company lasts long enough–and not even that long, really–the dead will outnumber the living. An excerpt about the author’s late aunt:

Observing that phenomenon is a strange thing. There she is, the person you love – you’re talking to her, squeezing her hand, thanking her for being there for you, watching the green zigzag move slower and slower – and then she’s not there anymore.

Another machine, meanwhile, was keeping her alive: some distant computer server that holds her thoughts, memories and relationships.

While it’s obvious that people don’t outlive their bodies on digital technology, they do endure in one sense. People’s experience of you as a seemingly living person can and does continue online.

How is our continuing presence in digital space changing the way we die? And what does it mean for those who would mourn us after we are gone?

Observing that phenomenon is a strange thing. There she is, the person you love – you’re talking to her, squeezing her hand, thanking her for being there for you, watching the green zigzag move slower and slower – and then she’s not there anymore.

Another machine, meanwhile, was keeping her alive: some distant computer server that holds her thoughts, memories and relationships.

While it’s obvious that people don’t outlive their bodies on digital technology, they do endure in one sense. People’s experience of you as a seemingly living person can and does continue online.

How is our continuing presence in digital space changing the way we die? And what does it mean for those who would mourn us after we are gone?•

Tags: Brandon Ambrosino