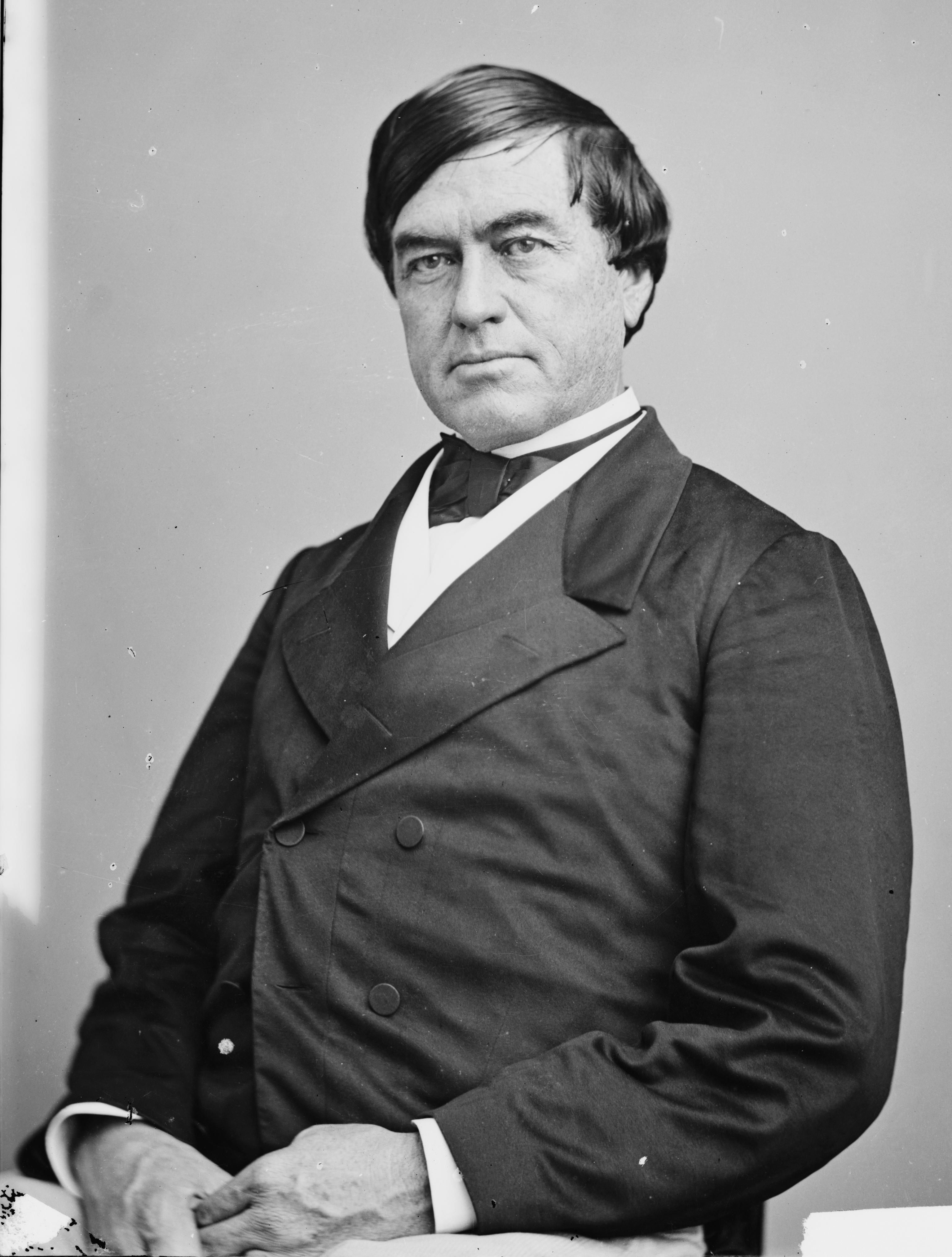

Cassius Marcellus Clay of Kentucky was a liberator, mostly.

A general who served the Union during the Civil War, he was an abolitionist from a family of slave owners who went mental in his dotage, essentially imprisoning a very reluctant 15-year-old wife when he was in his eighties. He was also a politician, an expert duelist, a Yale graduate and the U.S. Minister to Russia under President Lincoln. He was a wonderful and, eventually, terrible man.

It’s his post in St. Petersburg that reminded me of him, as he’s mentioned in a book I just read, Ian Frazier’s Travels in Siberia, which I consider to be part of an unofficial trilogy by the great reporter, along with Great Plains and On the Rez, of volumes by a tourist of sorts who lingers as long as you can without becoming a local.

From an article of the death of the nonagenarian in the July 23, 1903 New York Times:

Gen. Cassius Marcellus was famous for such a multitude of daring deeds, political feats, and personal eccentricities that it is hard to choose any one act or characteristic more distinguished than the rest. As a duelist, always victorious, he was said to have been implicated in more encounters and to have killed more men than any fighter living. As a politician he was especially famous for his anti-slavery crusades in Kentucky, having become imbued with abolition principles while he was a student at Yale, despite the fact that his father was a wealthy slave owner. As a diplomat while Minister to Russia during and after the civil war, he took a prominent part in the negotiations that resulted in the annexation of Alaska.

The act of Gen. Clay’s life that has commanded most attention in recent years was his marriage to a fifteen-year-old peasant girl after he had reached his eighty-fourth birthday. In 1887, he had married his first wife, Miss Warfield, a member of an aristocratic family of slave holders, and years afterward when he had become an ardent disciple of Tolstoi, he came to the conclusion that he ought to wed a “daughter of the people.” In November, 1894, he chose Dora Richardson, the daughter of a woman who had been a domestic for some time in his mansion at White Hall, near Lexington.

When the little girl became his wife, the General proceeded to employ a governess for her. She rebelled. Then he sent her to the same district school she had attended previously. The fact that he supplied her with the most beautiful French gowns and lavished money upon her, she did not consider compensations for the teasing she got at the hands of her fellow-pupils. In two months he had to take her back home, still uneducated.

The old warrior’s eccentricities increased during his declining years, and after his latest marriage he thought little of anything except his dream that some ancient enemy was trying to murder him and his “peasant wife,” as he called her. She, in spite of his kindnesses, kept running away from White Hall, and finally he decided he must get a divorce. This he did, charging her with abandonment. She soon married a worthless young mountaineer named Brock, who was once arrested for counterfeiting. Then the General began to plot to get her back, having already given a farm and house to her and her new husband, only to hear that Brock sold the property. At last Brock died, and a few months ago dispatches from Kentucky stated that the General was trying in vain to prevail upon his “child wife” to return to him. She refused persistently, never having outgrown the dislike for the luxurious life with which he surrounded her and still preferring the simple country existence to which she was born.•