It may have looked suspiciously like an open casket, but Alfred Hitchcock had a casting couch. He wasn’t the chaste monk of the macabre he made himself out to be. It was just a few years ago that Tippi Hedren described how her career was held hostage post-Birds by Hitchcock, all because she wouldn’t give in to his sexual blackmail.

Oriana Fallaci interviewed the British suspense master in 1963 when his crowpocalypse screened in Cannes, but while she had a good understanding of the cruelty beneath the surface of the filmmaker she so admired, she clearly was hoodwinked by his narrative of being a devoted, even sexless, husband, entitling the piece, “Mr. Chastity.” What follows is most of her introduction, which paints the director as tiresome and homophobic.

____________________________

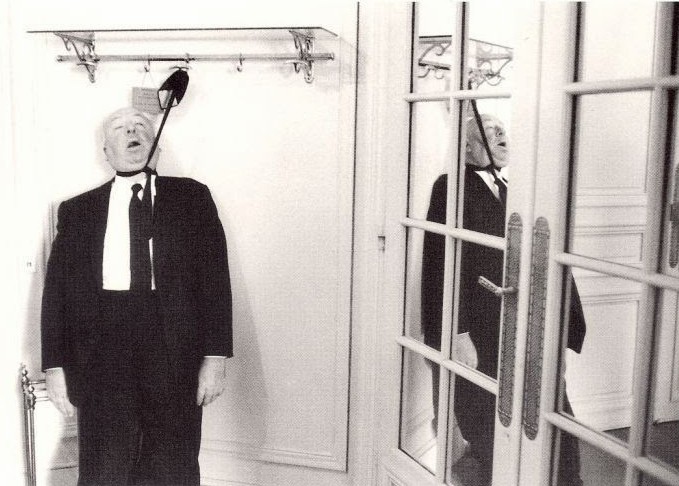

For years I had been wanting to meet Hitchcock. For years I had been to every Hitchcock film, read every article about Hitchcock, basked in contemplation of every photograph of Hitchcock: the one of him hanging by his own tie, the one of him reflected in a pool of blood, the one of him playing with a skull immersed in a bathtub. I liked everything about him: his big, Father Christmas paunch, his twinkling little pig eyes, his blotchy, alcoholic complexion, his mummified corpses, his corpses shut inside wardrobes, his corpses chopped into pieces and shut inside suitcases, his corpses temporarily buried beneath beds of roses, his anguished flights, his crimes, his suspense, those typically English jokes that make even death ridiculous and even vulgarity elegant. I might be wrong, but I cannot help laughing at the story about the two actors in the cemetery watching their friend being lowered into his grave. The first one says to the other, “How old are you, Charlie?” And Charlie answers, “Eighty-nine.” The first one then observes, “Then there’s no point in your going home, Charlie.” …

My opportunity to meet him and really kiss his hand came at the Cannes Festival, where Hitchcock was showing The Birds, a sinister film about birds that revolt against men and exterminate them by pecking them to death. Hitchcock was coming from Hollywood, and I rushed to Nice airport to greet him. Three hours later I was in his room on the fourth floor of the Carlton Hotel, gazing at him just as my journalist colleague, Veronique Passani, had gazed at Gregory Peck the first time she met him–and she had subsequently managed to marry him. Not that Hitchcock was handsome like Gregory Peck. To be objective, he was decidedly ugly: bloated, purple, a walrus dressed like a man–all that was missing was a mustache. The sweat, copious and oily, was pouring out of all that walrus fat, and he was smoking a dreadfully smelly cigar, which was pleasant only insofar as it obscured him for long moments behind a dense, bluish cloud. But he was Hitchcock, my dearest Hitchcock, my incomparable Hitchcock, and every sentence he spoke would be a pearl of originality and wit. In the same way that we assume that intellectuals are necessarily intelligent, and movie stars necessarily beautiful, and priests necessarily saintly, so I had assumed that Hitchcock was the wittiest man in the world.

He’s isn’t. The full extent of his humor is covered by five or six jokes, two or three macabre tricks, seven or eight lines that he has been repeating for years with the monotony of a phonograph record that’s stuck. Every time he opened a subject, in the sonorous voice of his, I foresaw how he would conclude; I already read it. Moreover, he would make his pronouncements as if he knew it himself: hands folded on his breast, eyes cast up toward the ceiling, like a child reciting a lesson learned by heart. Nor was there anything new about his admission of chastity, of complete lack of interest in sex. Everyone knows that Hitchcock has never known any woman other than his wife, has never desired any woman other than his wife; because he’s not interested in women. This doesn’t mean that he likes men, for heaven’s sake; such deviations are regarded by him with pained and righteous disgust. It only means for him sex does not exist; it would suit him fine if humanity were born in bottles. Nor, for him, does love exist, that mysterious impulse from which beings and things are born; the only thing that interests him in all creation is the opposite of whatever is born: whatever dies. If he sees a budding rose, his impulse, I am afraid, is to eat it.

With the blindness of all disciples or faithful admirers, I took some time to realize his failings. In fact our interview began with bursts of laughter for a good half-hour. But then the bursts of laughter became short little laughs, the short little laughs became smiles, the smile grew cold, and at a certain point I discovered that I could no longer raise a laugh, nor could I have done so even if he had tickled the soles of my feet. That was when I realized the most spine-chilling thing about him: his great wickedness. A person who invents horrors for fun, who makes a living frightening people, who only talks about crimes and anguish, can’t really be evil, so I thought. He is, though. He really enjoys frightening people, knowing that every now and then somebody dies of a heart attack watching his movies, reading that from time to time a man kills his wife the way a wife is killed in one of his movies. Not knowing all the criminals whose master he has been is sheer torture to him. He would like to know about all such authors, to compliment each one and offer him a cigar. Because he can laugh about death with the wisdom of the sages? No, no. Because he likes death. He likes it the way a gravedigger likes it.•