Aaron Burr, statesman and murderer, was, as Lin-Manuel Miranda describes him, the “damn fool” who shot Alexander Hamilton. Burr’s own death was less dramatic, though there was some small-scale intrigue which accompanied it.

Burr spent his last days reclusively on Staten Island, New York. He was a decidedly shadowy figure in the borough, and his funeral services were lightly attended. But there was one entrepreneur who kept a close check on the former Vice President during his waning moments. He had his reasons. An excerpt from an article in the September 8, 1895 New York Times:

It is not generally known that Aaron Burr spent the last days of his life and died on Staten Island. A few paces back from the Staten Island Ferry landing, at Port Richmond, stands the St. James Hotel, which is anything but a pretentious structure, and was originally a two-story boarding house in the year 1836, kept by a couple named Edgerton. It was during the early part of that year that Burr took a room there, and Mrs. Edgerton became his faithful servant and nurse. He sought seclusion and peace for his last days on earth, and, to an extent, found his desire within the great city of his choice, where he had realized the greatest triumphs of his life. The town was then composed of but a few scattered houses, and the Jersey shore was covered with a pine forest to the water’s edge, a clear view of which could be had from this old dwelling house. He rarely left his room, which was the front apartment on the second floor, now used as a parlor in the hotel. The furniture was antique and the room about eighteen feet square. The bed upon which Burr died was an old-fashioned, four-post, chintz-curtained one. Over the mantel now hangs a profile steel engraving of Burr, undoubtedly cut from some biography of the man, simply framed, to which, until recently, there was attached the inscription: ‘Aaron Burr died in this room Sept. 14, 1836.’

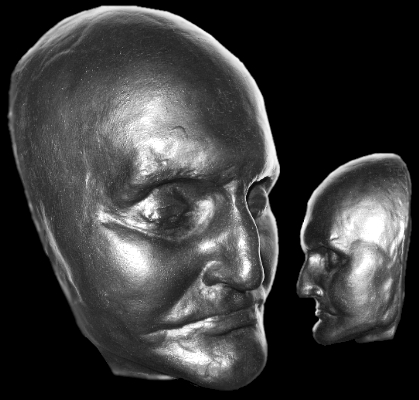

Upon rare occasions, and when he was confident that he would not be noticed, he wandered a short distance from his place of refuge, but the old man was too well known by the villagers to escape observation, and many eyes were upon him at every step, the villagers being proud of their visitor and observant of every action of so celebrated a man. He was an under-sized, sparsely built old man at this time, but he was also, to the end, erect and soldierly in bearing. His attire was always very fine, and he dressed with the utmost neatness, was quite the aristocratic gentleman of the old school, and the refinement and elegance of his manner were invariably conspicuous. He could be singularly winning and gentle even with the humblest. His complexion was pale and like parchment for years before his death, and at this time he was upward of eighty years of age. The dignity of his face was slightly marred by a thin, aquiline nose, which had a decided bend to one side, either through some accident or by nature’s malformation. Despite his advanced age, his eyes were keen and magnetic to a remarkable degree. He had learned or rather grown to dislike the curiosity seeker, and finding that he could not take his short walks abroad without being gazed at continually by the natives of Staten Island, he became more seclusive as the days went by, and finally refused to leave his room. In this room, rendered historic by his presence, this old decrepit, wornout, once great man passed his time with memories and sought consolation in the love letters of the women who had once loved him, among which were those of Mme. Jumel, filed with affectionate regard and regrets that a cruel fate had separated them. All those letters were scattered about his room, and when he died hundreds of such letters loose and in packages tied with ribbons were scattered upon his bed and upon the floor of the chamber. Among the evidences of his intriguing disposition, not at accusers, but as tokens of the loves of his victims, the old man breathed his last. …

The old man had no attendant. He lived alone, with his old joys and his new sorrows, waiting for death to claim him and take him he knew and seemed to care not whither. A mysterious stranger haunted the house for many days and nights before the death of Burr. He never was admitted to the recluse, but always made interested inquiries concerning his health, and he was supposed to be either a relative or interested friend of the statesman, although he was neither. This man was faithful to the determination, and almost immediately after Aaron Burr’s death put in an appearance, and, without saying, “By your leave,” opened his satchel and proceeded, as if he had a right to do so, to take a plaster cast of the dead man.•