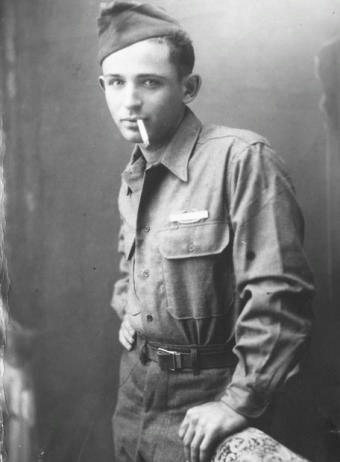

Oriana Fallaci and Norman Mailer, the Electra and Oedipus of the Apollo space program, were two writers with egos massive enough to observe humankind’s mission to the Moon as not only material for New Journalism reportage of an historical quest but also as backdrop to investigations of their own psyches. In 1967, the year after Fallaci published If the Sun Dies… and two years before Mailer stormed through a series of long-form articles for Life magazine that became Of a Fire on the Moon, the pair sat down for an interview with Fallaci serving as the inquisitor. In Mailer’s face–“noble and vulgar,” she called it–Fallaci claimed to be searching for America. It actually wasn’t a bad place to look: Like his country, Mailer could be at turns soaringly brilliant and shockingly brutal–and completely delusional about his behavior in regards to the latter. His remarks about domestic violence, for instance, were beyond horrifying, and they unfortunately weren’t merely macho showboating. The discussion opened Fallaci’s collection of (mostly) non-political interrogations, The Egotists. Three excerpts follow.

_____________________________

Oriana Fallaci:

The problem I want to talk about is a difficult one, but we have to deal with it. The fact is we Europeans used to love you Americans. When you came to liberate us twenty years ago, we used to look up to you as if you were angels. And now many of us don’t love you anymore; indeed some hate you. Today the United States might be the most hated country in the world.

Norman Mailer:

You used to love us because love is hope, and we Americans were your hope. And also, perhaps, because twenty years ago we were a better people, although not as good as you believed then–the seeds of the present ugliness were already there. The soldiers with whom I fought in the Pacific, for example, were a little better than the ones who are fighting now in Vietnam, but not by much. We were quite brutal even then. One could write a novel about Vietnam along the lines of The Naked and the Dead, and the characters would not need to be worse than they are in the book.The fact is that you have lost the hope you have vested in us, and so you have lost your love; therefore you see us in a much worse light than you did before, and you don’t understand that the roots of our ugliness are the old ones. It is true that the evil forces in America have triumphed only after the war–with the enormous growth of corporations and the transformation of man into mass-man, the alienation of men from their own existence–but these forces were already there in Roosevelt’s time. Roosevelt, you see, was a great President, but he wasn’t a great thinker. Indeed, he was a very superficial one. When he took power, America stood at a crossroad; either a proletarian revolution would take place or capitalism would enter a new phase. What happened was that capitalism took a new turn, transforming itself into a subtle elaboration of state capitalism–it is not by chance that the large corporations in effect belong to the government. They belong to the right. And just as the Stalinists have murdered Marxism, so these bastards of the right are now destroying what is good in American life. They are the same people who build the expressways, who cut the trees, who pollute the air and the water, who transform life into a huge commodity.

Oriana Fallaci:

We Europeans are also very good at this. I mean this is not done by only right-wing Americans.

Norman Mailer:

Of course. It is a worldwide process. But its leader is America, and this is why we are hated. We are the leaders of the technological revolution that is taking over the twentieth century, the electronic revolution that is dehumanizing mankind.•

_____________________________

Norman Mailer:

I still have hope you seem to have lost. Because of the youth. Some of them are subhuman, but most of them are intelligent.

Oriana Fallaci:

That is true. But they are also stuffed with drugs, violence, LSD. Does that help your hoping?

Norman Mailer:

Theirs is an extraordinary complex generation to live in. The best thing I can say about them is that I can’t understand them. The previous generation, the one fifteen years ago, was so predictable, without surprises. This one is a continuing surprise. I watch the young people of today, I listen to them, and l realize that I’m not twenty years older than they are but a hundred. Perhaps because in five years they went through changes that usually take half a century to complete, their intelligence has been speeded up so incredibly that there is no contact between them and the generation around thirty. Not to speak of those around forty or fifty. Yes, I know that this does not happen only in America; this too is a global process. But the psychology of American youth is more modern than that of any other group in the world; it belongs not to 1967 but to 2027. If God could see what would happen in the future–as he perhaps does–he would see people everywhere acting and thinking in 2027 as American youth do now. It’s true they take drugs. But they don’t take the old drugs such as heroin and cocaine that produce only physical reactions and sensations and dull you at the same time. They take LSD, a drug that can help you explore your mind. Now let’s get this straight: I can’t justify the use of LSD. I know too well that you don’t get something for nothing, and it may well be that we’ll pay a tragic price for LSD: it seems that it can break the membrane of the chromosomes in the cells and produce who knows what damage in future children. But LSD is part of a search, a desperate search, as if all these young people felt at the same time the need to explore as soon as possible their minds so as to avoid a catastrophe. Technology has stripped our minds until we have become like pygmies driving chariots drawn by dinosaurs. Now, if we want to keep the dinosaurs in harness, our minds will have to develop at a forced pace, which will require a frightening effort. The young have felt the need to harness the dinosaurs, and if they have found the wrong means, it’s still better than nothing. My fear had been that America was slowly freezing and hardening herself in a pygmy’s sleep. But no, she’s awake.•

_____________________________

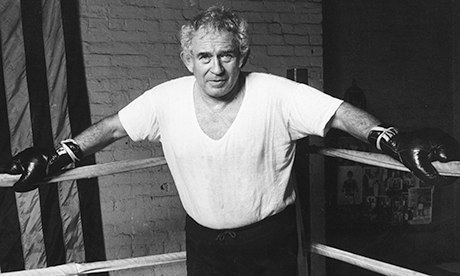

Norman Mailer:

Damn it, I don’t like violence. But there’s something I like even less, and that’s a need for security. It smells of the grave and forces you to react with blood.

Oriana Fallaci:

You dislike violence? You who knifed a wife and can’t miss a boxing match?

Norman Mailer:

The knife in my wife’s belly was a crime. It was a grave crime, but it had nothing to do with violence. And as for the fights, well, boxing is not violence. It’s a conversation, an exchange between two men who talk to each other with their hands instead of their voices: hitting at the ear, the nose, the mouth, the belly, instead of hitting at each other’s minds. Boxing is a noble art. When a man fights in a ring, he is not expressing brutality. He expresses a complex, subtle nature like that of a true intellectual, a real aristocrat. A pugilist is less brutal, or not at all brutal after a fight, because with his fists he transforms violence into something beautiful, noble and disciplined. It’s a real triumph of the spirit. No, I’m not violent. To be violent means to pick fights, and I can’t remember ever having started a fight. Nor can I remember ever having hit a woman–a strange woman, I mean. I may have hit a wife, but that’s different. If you are married you have two choices: either you beat your wife, or you don’t. Some people live their whole life without ever beating her, others maybe beat her once and thereon are labeled “violent.” I like to marry women whom I can beat once in a while, and who fight back. All my wives have been very good fighters. Perhaps I need women who are capable of violence, to offset my own. Am I not American, after all? But the act of hitting is hateful because it implies a judgement, and judgement itself is hateful. Not that I think of myself as being a good man in the Christian sense. But at certain times I have a clear consciousness of what is good and what is evil, and then my concept of the good resembles that of the Christian.•