In a series of articles in the New York Review of Books over the last couple of years, Sue Halpern has taken a thought-provoking look at the dubious side of the Digital Era, considering the impact of tech billionaires, technological unemployment and the Internet of Things.

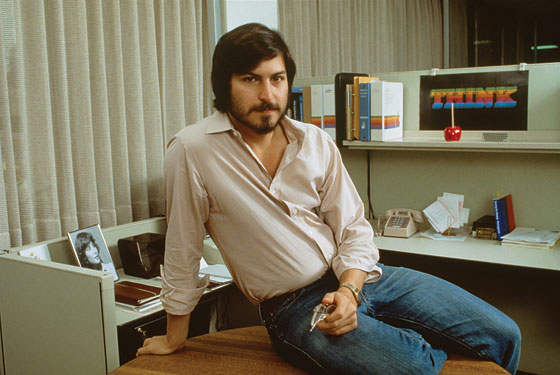

Her latest salvo tries to locate the real legacy of Steve Jobs, who was mourned equally in office parks and Zuccotti Park. In doing so she calls on the two recent films on the Apple architect, Alex Gibney’s and Danny Boyle’s, and the new volume about him by Brent Schlender and Rick Tetzeli. Ultimately, the key truth may be that Jobs used a Barnum-esque “magic” and marketing myths to not only sell his new machines but to plug them into consumers’ souls.

An excerpt:

So why, Gibney wonders as his film opens—with thousands of people all over the world leaving flowers and notes “to Steve” outside Apple Stores the day he died, and fans recording weepy, impassioned webcam eulogies, and mourners holding up images of flickering candles on their iPads as they congregate around makeshift shrines—did Jobs’s death engender such planetary regret?

The simple answer is voiced by one of the bereaved, a young boy who looks to be nine or ten, swiveling back and forth in a desk chair in front of his computer: “The thing I’m using now, an iMac, he made,” the boy says. “He made the iMac. He made the Macbook. He made the Macbook Pro. He made the Macbook Air. He made the iPhone. He made the iPod. He’s made the iPod Touch. He’s made everything.”

Yet if the making of popular consumer goods was driving this outpouring of grief, then why hadn’t it happened before? Why didn’t people sob in the streets when George Eastman or Thomas Edison or Alexander Graham Bell died—especially since these men, unlike Steve Jobs, actually invented the cameras, electric lights, and telephones that became the ubiquitous and essential artifacts of modern life?* The difference, suggests the MIT sociologist Sherry Turkle, is that people’s feelings about Steve Jobs had less to do with the man, and less to do with the products themselves, and everything to do with the relationship between those products and their owners, a relationship so immediate and elemental that it elided the boundaries between them. “Jobs was making the computer an extension of yourself,” Turkle tells Gibney. “It wasn’t just for you, it was you.”•

Tags: Brent Schlender, Rick Tetzeli, Steve Jobs, Sue Halpern