Losing the first leg of the Space Race ultimately proved beneficial to the U.S. The jolt of the Soviet Sputnik 1 success spurred the government to establish DARPA and fund the ARPANET, which, of course, eventually became the Internet.

Another profound consequence of the Cold War satellite race was the creation of Astrobiology, a field that couldn’t quite form until Sputnik’s brilliant blast provided it with its raison d’être. In a beautifully written Nautilus piece, Caleb Scharf traces the branch’s beginnings, which were propelled in the late 1950s by forward-thinking American scientist Joshua Lederberg, who, to paraphrase Leonard Cohen, saw the future and thought it might be murder. His work and warnings put our forays into the final frontier, as Scharf writes, in “bio-containment lockdown,” which was fortunate.

By the 1990s, the mission of astrobiology had morphed and become immense, and it will likely grow larger still as we press further across the universe.

The opening:

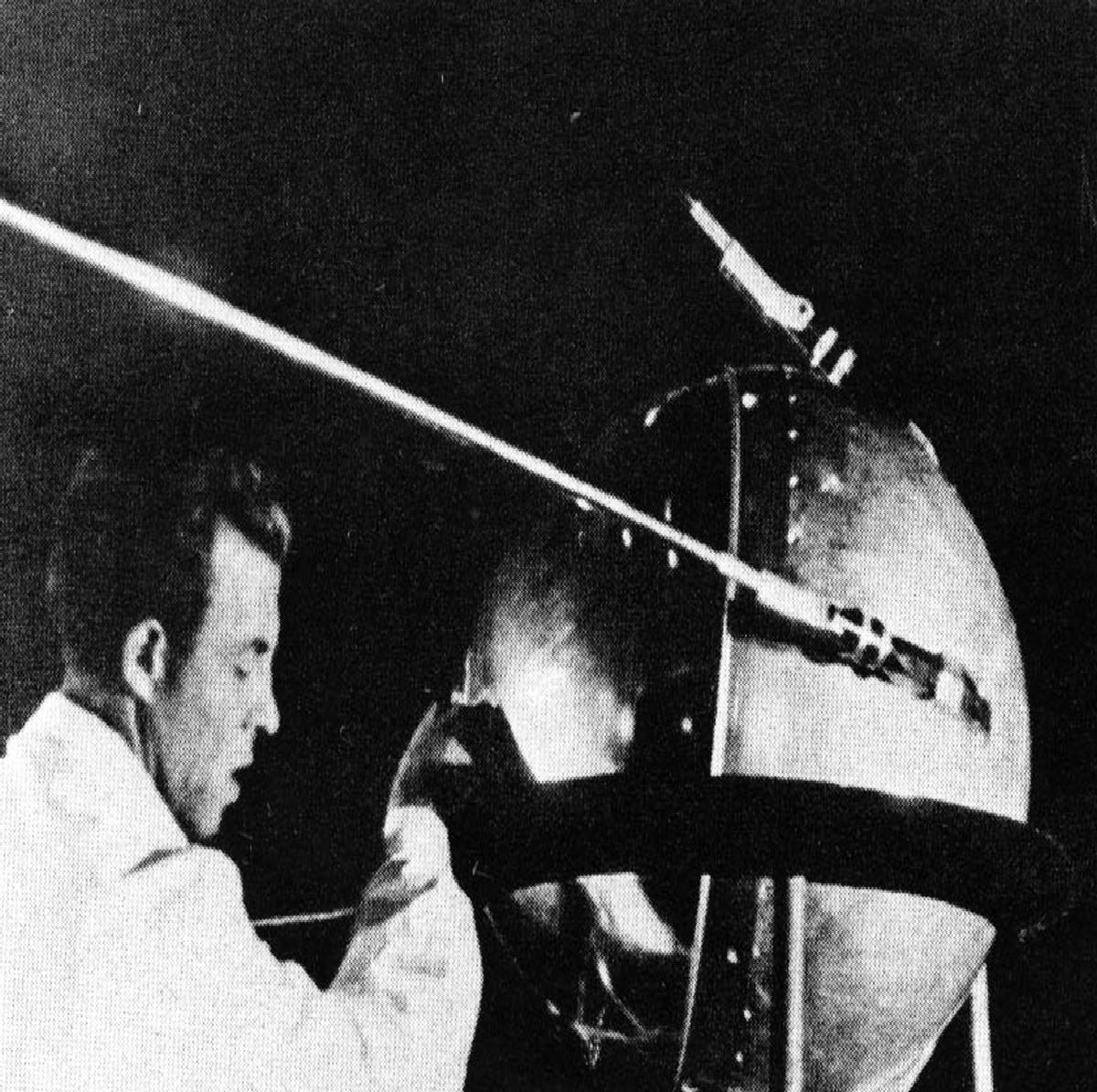

Astronomy and biology have been circling each other with timid infatuation since the first time a human thought about the possibility of other worlds and other suns. But the melding of the two into the modern field of astrobiology really began on Oct. 4, 1957, when a 23-inch aluminum sphere called Sputnik 1 lofted into low Earth orbit from the desert steppe of the Kazakh Republic. Over the following weeks its gently beeping radio signal heralded a new and very uncertain world. Three months later it came tumbling back through the atmosphere, and humanity’s small evolutionary bump was set on a trajectory never before seen in 4 billion years of terrestrial history.

At the time of the ascent of Sputnik, a 32-year-old American called Joshua Lederberg was working in Australia as a visiting professor at the University of Melbourne. Born in 1925 to immigrant parents in New Jersey, Lederberg was a prodigy. Quick-witted, generous, and with an incredible ability to retain information, he blazed through high school and was enrolled at Columbia University by the time he was 15. Earning a degree in zoology and moving on to medical studies, his research interests diverted him to Yale. There, at age 21, he helped research the nascent field of microbial genetics, with work on bacterial gene transfer that would later earn him a share of the 1958 Nobel Prize.

Like the rest of the planet, Australia was transfixed by the Soviet launch; as much for the show of technological prowess as for the fact that a superpower was now also capable of easily lobbing thermonuclear warheads across continents. But, unlike the people around him, Lederberg’s thoughts were galvanized in a different direction. He immediately knew that another type of invisible wall had been breached, a wall that might be keeping even more deadly things at bay, as well as incredible scientific opportunities.

If humans were about to travel in space, we were also about to spread terrestrial organisms to other planets, and conceivably bring alien pathogens back to Earth. As Lederberg saw it, either we were poised to destroy indigenous life-forms across our solar system, or ourselves. Neither was an acceptable option.•

_______________________________

“This is the beginning of a new era for mankind.”

Tags: Caleb Scharf, Joshua Lederberg