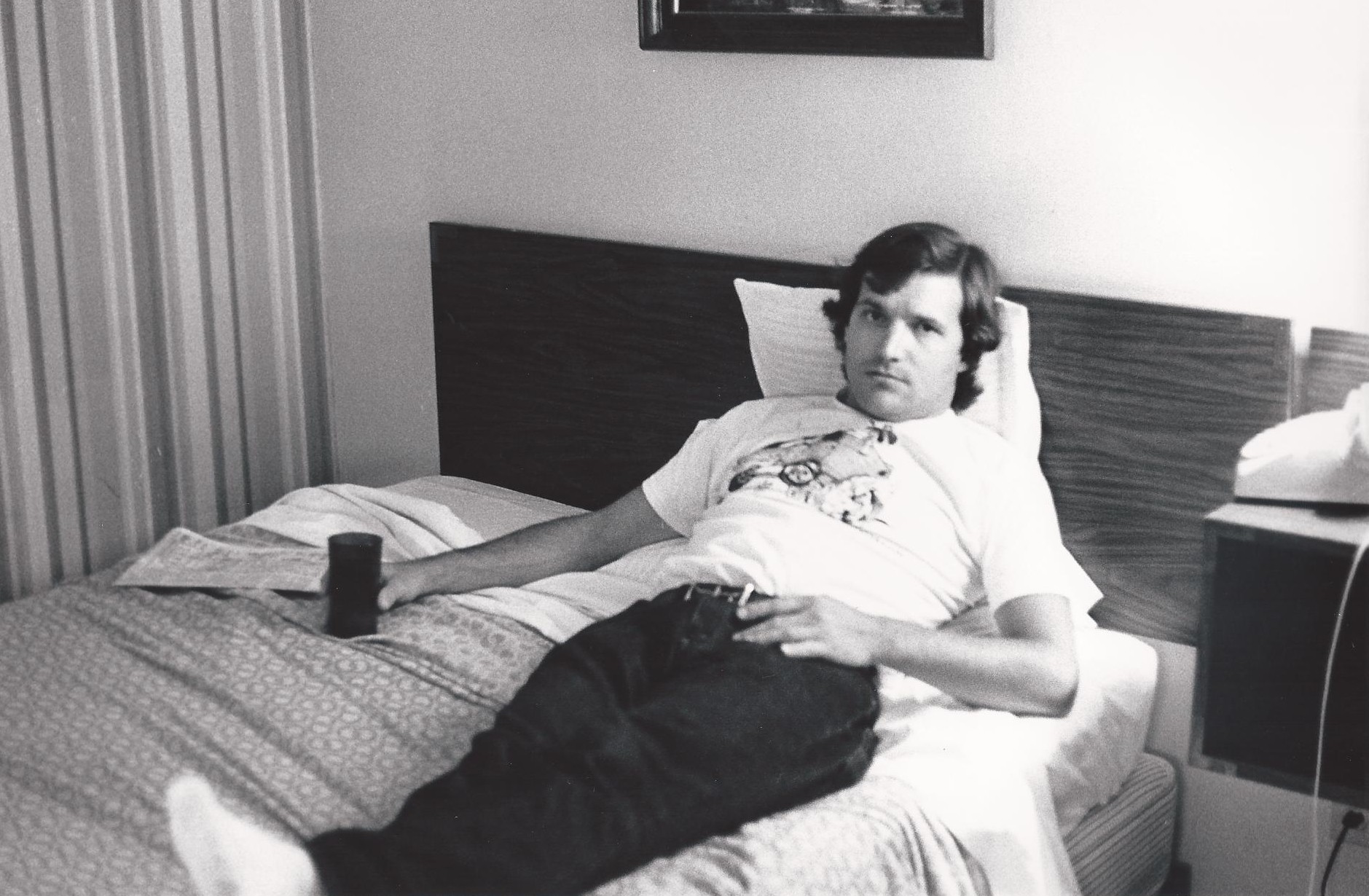

Lucian Truscott IV, the great, great, great, great grandson of Thomas Jefferson and graduate of the United States Military Academy, began his writing career penning pieces on hippies and heroin addiction, eventually making his mark at the Village Voice and Rolling Stone. In 1972, he was assigned by the former to review Hunter S. Thompson’s genius, drug-fuelled phantasmagoria Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. An excerpt:

Hunter Thompson lived in Aspen then, and his ranch, located outside town about 10 miles, tucked away up a valley with National Forest land on every side, was the first place I stopped. It was late afternoon and Thompson was just getting up, bleary-eyed and beaten, shaded from the sun by a tennis hat, sipping a beer on the front porch.

I got to know him while I was still in the Army in the spring of 1970, when he and a few other local crazies were gearing up for what would become the Aspen Freak Power Uprising, a spectacular which featured Thompson as candidate for sheriff, with his neighbor Billy for coroner. They ran on a platform which promised, among other things, public punishment for drug dealers who burned their customers, and a campaign guaranteed to rid the valley of real estate developers and ‘nazi greedheads’ of every persuasion. In a compromise move toward the end of the campaign, Thompson promised to “eat mescaline only during off-duty hours.” The non-freak segment of the voting public was unmoved and he was eventually defeated by a narrow margin.

In the days before the Freak Power spirit, Thompson’s ranch served as a war room and R&R camp for the Aspen political insurgents. Needless to say there was rarely a dull moment. When I arrived last summer, however, things had changed. Thompson was in the midst of writing a magnum opus, and it was being cranked out at an unnerving rate. I was barely across the threshold when I was informed that he worked (worked?) Monday through Friday and saved the weekends for messing around. As usual, he worked from around midnight until 7 or 8 in the morning and slept all day. There was an edge to his voice that said he meant business. This was it. This was a venture that had no beginning or end, that even Thompson himself was having difficulty controlling.

“I’m sending it off to Random House in 20,000-word bursts,” he said, drawing slowly on his ever-present cigarette holder. “I don’t have any idea what they think of it. Hell, I don’t have any idea what it is.”

“What’s it about?” I asked.

“Searching for The American Dream in Las Vegas,” replied Thompson coolly.•

In 1974, Truscott, again representing the Voice, tagged along with another gonzo character, Evel Knievel, at the time of his Snake River Canyon spacecycle jump, a spectacle promoted (in part) by professional wrestling strongman Vince McMahon Jr. Truscott shows up in this awesome video at 6:22, giving the event all the respect it deserved while simultaneously summing up his reporting career. (Because of privacy settings, you have to click through and watch it on the Vimeo site.)

___________________________

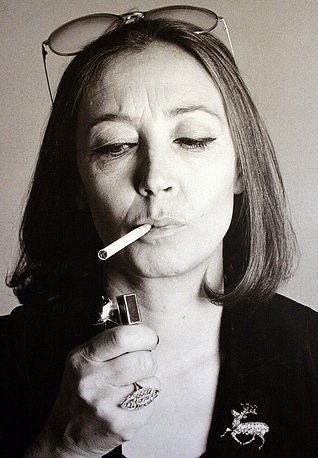

Oriana Fallaci did as much serious journalism as anyone during her era, but she wasn’t above the lurid if the story was good and the check likely to clear. Case in point: Her 1967 Look magazine article “The Dead Body and the Living Brain,” about pioneering head-transplant experimentation. In the piece, Fallaci reports on the sci-fi-ish experiments that Prof. Robert White was conducting with rhesus monkeys at a time when consciousness about animal rights was on the rise. The opening:

Libby had eaten her last meal the night before: orange, banana, monkey chow. While eating she had observed us with curiosity. Her hands resembled the hands of a newly born child, her face seemed almost human. Perhaps because of her eyes. They were so sad, so defenseless. We had called her Libby because Dr. Maurice Albin, the anesthetist, had told us she had no name, we could give her the name we liked best, and because she accepted it immediately. You said “Libby!” and she jumped, then she leaned her head on her shoulder. Dr. Albin had also told us that Libby had been born in India and was almost three years, an age comparable to that of a seven-year-old girl. The rhesuses live 30 years and she was a rhesus. Prof. Robert White uses the rhesus because they are not expensive; they cost between $80 and $100. Chimpanzees, larger and easier to experiment with, cost up to $2,000 each. After the meal, a veterinarian had come, and with as much ceremony as they use for the condemned, he had checked to be sure Libby was in good health. It would be a difficult operation and her body should function as perfectly as a rocket going to the moon. A hundred times before, the experiment had ended in failure, and though Professor White became the first man in the entire history of medicine to succeed, the undertaking still bordered on science fiction. Libby was about to die in order to demonstrate that her brain could live isolated from her body and that, so isolated, it could still think.•

Fallaci wasn’t always insightful when assessing her subjects, missing out entirely on Indira Gandhi’s dictatorial leanings and Alfred Hitchcock’s deep seediness, but she was accurate in her judgment of Muammar el-Qaddafi when conversing with that shock jock Charlie Rose in 2003.

___________________________

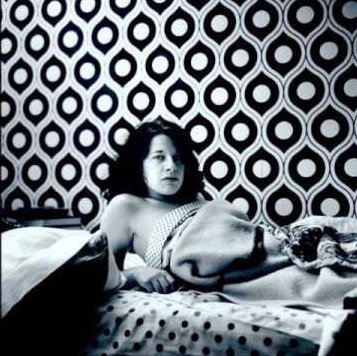

In Fran Lebowitz’s 1993 Paris Review Q&A, the writer’s maternal nature, or something like it, came to the fore. An excerpt:

Question:

Young people are often a target for you.

Fran Lebowitz:

I wouldn’t say that I dislike the young. I’m simply not a fan of naïveté. I mean, unless you have an erotic interest in them, what other interest could you have? What are they going to possibly say that’s of interest? People ask me, Aren’t you interested in what they’re thinking? What could they be thinking? This is not a middle-aged curmudgeonly attitude; I didn’t like people that age even when I was that age.

Question:

Well, what age do you prefer?

Fran Lebowitz:

I always liked people who are older. Of course, every year it gets harder to find them. I like people older than me and children, really little children.

Question:

Out of the mouths of babes comes wisdom?

Fran Lebowitz:

No, I’m just intrigued by them, because, to me, they’re like talking animals. Their consciousness is so different from ours that they constitute a different species. They don’t have to be particularly interesting children; just the fact that they are children is sufficient. They don’t know what anything is, so they have to make it up. No matter how dull they are, they still have to figure things out for themselves. They have a fresh approach.•

In this 1977 Canadian talk show, Lebowitz, selling her book Metropolitan Life, was concerned that digital watches and calculators and other new technologies entitled kids (and adults also) to a sense of power they should not have. She must be pleased with smartphones today.