In a 1968 Playboy Interview, Eric Nordern tried to extract a definitive statement about the meaning of 2001: A Space Odyssey directly from the mouth of the horse, but Stanley Kubrick wasn’t having it. The director was happy, however, to expound on the potential existence of extraterrestrials of advanced intelligence and what it would mean for us relatively lowly earthlings. An excerpt:

Playboy:

Speaking of what it’s all about—if you’ll allow us to return to the philosophical interpretation of 2001—would you agree with those critics who call it a profoundly religious film?

Stanley Kubrick:

I will say that the God concept is at the heart of 2001—but not any traditional, anthropomorphic image of God. I don’t believe in any of Earth’s monotheistic religions, but I do believe that one can construct an intriguingscientific definition of God, once you accept the fact that there are approximately 100 billion stars in our galaxy alone, that its star is a life-giving sun and that there are approximately 100 billion galaxies in just the visibleuniverse. Given a planet in stable orbit, not too hot and not too cold, and given a few billion years of chance chemical reactions created by the interaction of sun’s energy on the planet’s chemicals, it’s fairly certain that life in one form or another will eventually emerge. It’s reasonable to assume that there must be, in fact, countless billions of such planets where biological life has arisen, and the odds of some proportion of such life developing intelligence are high. Now, the sun is by no means an old star, and its planets are mere children in cosmic age, so it seems likely that there are billions of planets in the universe not only where intelligent life is on a lower scale than man but other billions where it is approximately equal and others still where it is hundreds of thousands of years in advance of us. When you think of the giant technological strides that man has made in a few millennia—less than a microsecond in the cosmology of the universe—can you imagine the evolutionary development that much older life forms have taken? They may have progressed from biological species, which are fragile shells for the mind at best, into immortal machine entities—and then, over innumerable eons, they could emerge from the chrysalis of matter transformed into beings of pure energy and spirit. Their potentialities would be limitless and their intelligence ungraspable by humans.

Playboy:

Even assuming the cosmic evolutionary path you suggest, what has this to do with the nature of God?

Stanley Kubrick:

Everything—because these beings would be gods to the billions of less advanced races in the universe, just as man would appear a god to an ant that somehow comprehended man’s existence. They would possess the twin attributes of all deities—omniscience and omnipotence. These entities might be in telepathic communication throughout the cosmos and thus be aware of everything that occurs, tapping every intelligent mind as effortlessly as we switch on the radio; they might not be limited by the speed of light and their presence could penetrate to the farthest corners of the universe; they might possess complete mastery over matter and energy; and in their final evolutionary stage, they might develop into an integrated collective immortal consciousness. They would be incomprehensible to us except as gods; and if the tendrils of their consciousness ever brushed men’s minds, it is only the hand of God we could grasp as an explanation.

Playboy:

If such creatures do exist, why should they be interested in man?

Stanley Kubrick:

They may not be. But why should man be interested in microbes? The motives of such beings would be as alien to us as their intelligence.

Playboy:

In 2001, such incorporeal creatures seem to manipulate our destinies and control our evolution, though whether for good or evil—or both, or neither—remains unclear. Do you really believe it’s possible that man is a cosmic plaything of such entities?

Stanley Kubrick:

I don’t really believe anything about them; how can I? Mere speculation on the possibility of their existence is sufficiently overwhelming, without attempting to decipher the motives. The important point is that all the standard attributes assigned to God in our history could equally well be the characteristics of biological entities who billions of years ago were at a stage of development similar to man’s own and evolved into something as remote from man as man is remote from the primordial ooze from which he first emerged.

Playboy:

In this cosmic phylogeny you’ve described, isn’t it possible that there might be forms of intelligent life on an even higher scale than these entities of pure energy—perhaps as far removed from them as they are from us?

Stanley Kubrick:

Of course there could be; in an infinite, eternal universe, the point is that anything is possible, and it’s unlikely that we can even begin to scratch the surface of the full range of possibilities. But at a time when man is preparing to set foot on the Moon, I think it’s necessary to open up our Earth bound minds to such speculation. No one knows what’s waiting for us in our universe. I think it was a prominent astronomer who wrote recently, “Sometimes I think we are alone, and sometimes I think we’re not. In either case, the idea is quite staggering.”

Playboy:

You said that there must be billions of planets sustaining life that is considerably more advanced than man but has not yet evolved into non- or suprabiological forms. What do you believe would be the effect on humanity if the Earth were contacted by a race of such ungodlike but technologically superior beings?

Stanley Kubrick:

There’s a considerable difference of opinion on this subject among scientists and philosophers. Some contend that encountering a highly advanced civilization—even one whose technology is essentially comprehensible to us—would produce a traumatic cultural shock effect on man by divesting him of his smug ethnocentrism and shattering the delusion that he is the center of the universe. Carl Jung summed up this position when he wrote of contact with advanced extraterrestrial life that “reins would be torn from our hands and we would, as a tearful old medicine man once said to me, find ourselves ‘without dreams’ … we would find our intellectual and spiritual aspirations so outmoded as to leave us completely paralyzed.” I personally don’t accept this position, but it’s one that’s widely held and can’t be summarily dismissed.

In 1960, for example, the Committee for Long Range Studies of the Brookings Institution prepared a report for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration warning that even indirect contact—i.e., alien artifacts that might possibly be discovered through our space activities on the Moon, Mars, or Venus or via radio contact with an interstellar civilization—could cause severe psychological dislocations. The study cautioned that “Anthropological files contain many examples of societies, sure of their place in the universe, which have disintegrated when they have had to associate with previously unfamiliar societies espousing different ideas and different life ways; others that survived such an experience usually did so by paying the price of changes in values and attitudes and behaviour.” It concluded that since the consequences of any such discovery are “presently unpredictable,” it was advisable that the government initiate continuing studies on the psychological and intellectual impact of confrontation with extra-terrestrial life. What action was taken on this report I don’t know, but I assume that such studies are now under way. However, while not discounting the possible adverse emotional impact on some people, I would personally tend to view such contact with a tremendous amount of excitement and enthusiasm. Rather than shattering our society, I think it could immeasurably enrich it.

Another positive point is that it’s a virtual certainty that all intelligent life at one stage in its technological development must have discovered nuclear energy. This is obviously the watershed of any civilization; does it find a way to use nuclear power without destruction and harness it for peaceful purposes, or does it annihilate itself? I would guess that any civilization that has existed for a few thousand years after its discovery of atomic energy has devised a means of accommodating itself to the bomb, and this could prove tremendously reassuring to us—as well as give us specific guidelines for our own survival. In any case, as far as cultural shock is concerned, my impression is that the attention span of most people is quite brief; after a week or two of great excitement and over-saturation in the newspapers and on television, the public’s interest would drop off and the United Nations, or whatever world body we had then, would settle down to discussions with the aliens.

Playboy:

You’re assuming that extraterrestrials would be benevolent. Why?

Stanley Kubrick:

Why should a vastly superior race bother to harm or destroy us? If an intelligent ant suddenly traced a message in the sand at my feet reading, “I am sentient; let’s talk things over,” I doubt very much that I would rush to grind him under my heel. Even if they weren’t superintelligent, though, but merely more advanced than mankind, I would tend to lean more toward the benevolence, or at least indifference, theory. Since it’s most unlikely that we would be visited from within our own solar system, any society capable of traversing light-years of space would have to have an extremely high degree of control over matter and energy. Therefore, what possible motivation for hostility would they have? To steal our gold or oil or coal? It’s hard to think of any nasty intention that would justify the long and arduous journey from another star.•

Introduced by Vernon Myers, the publisher of Look, the 1966 short film, “A Look Behind the Future,” focuses on the magazine’s former photographer Kubrick, who was then in the process of making 2001: A Space Odyssey at London’s MGM studios. It’s a nice companion piece to Jeremy Bernstein’s two great New Yorker articles about the movie during its long gestation (here and here).

Mentioned or seen in this video: Mobile phones, laptop computers, Wernher Von Braun, memory helmets, a 38-ton centrifuge, Arthur C. Clarke at the Long Island warehouse where the NASA L.E.M. (Lunar Excursion Module) was being constructed, Keir Dullea meeting the press, etc.

_____________________________

I would think I’m in the small minority of Don DeLillo readers who feel that his best novel is White Noise, a book about an airborne toxic event and other looming threats. From Nathaniel Rich’s just-published Daily Beast piece:

How did the novel that Don DeLillo originally titled Panasonic become the phenomenon that was, and still is, White Noise? Canonized at birth by rhapsodic critics and instantly ubiquitous on college syllabi, the novel won the National Book Award and journalists hailed its publicity-shy author as a prophet.

But White Noise was not different in kind from Don DeLillo’s previous seven novels. He had been writing about the same paranoiac themes for 15 years: nuclear age anomie, the tyranny and mind control of American commercial excess, the dread of mass terror and the perverse longing for it, the aphasic cacophony of mass information, and even Hitler obsession. In those earlier novels DeLillo had written in the same clipped, oracular prose, borrowing sardonically from bureaucratic officialese, scientific jargon, and tabloid headlines. Some of White Noise’s main insights—“All plots tend to move deathward,” declares the narrator, Jack Gladney—were recycled from the earlier novels, too. White Noise was more conventionally plotted than End Zone, Great Jones Street, or Players, and the characters more conflicted, more human. But something else had changed.

“The greater the scientific advance,” says Jack Gladney, “the more primitive the fear.” White Noise is bathed in the glare and hum of personal computers and refrigerators and color televisions. Like bulletins from the subconscious, the text is intermittently interrupted by litanies of brand names designed to be pronounceable in a hundred languages: Tegrin, Denorex, Selsun Blue. At one point Jack observes his daughter talking in her sleep, uttering the words Toyota Celica. “It was like the name of an ancient power in the sky, tablet-carved in cuneiform. It made me feel that something hovered.”

Something is hovering all right.•

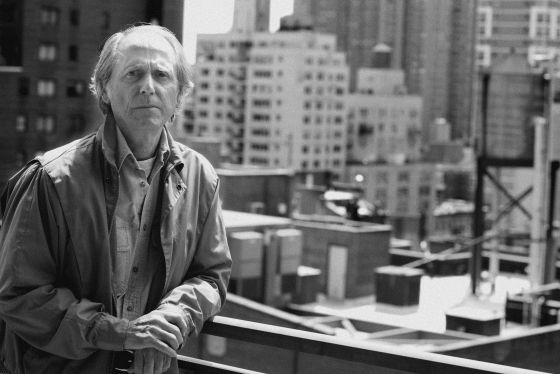

The 1991 BBC program, Don DeLillo: The Word, The Image, and The Gun, was originally aired the same year the author published that strange thing Mao II, a novel with wooden characters and plotting, but one so eerily correct about the coming escalation of terrorism, how guns would become bombs and airplanes would not just be redirected but repurposed. It’s like DeLillo tried to alert us to targets drawn in chalk on all sides of the Twin Towers, but we never really fully noticed. This program is a great portrait of DeLillo and his “dangerous secrets” about technology, surveillance, film, news, the novel, art and the apocalypse.

_____________________________

The 1980 killing of Scarsdale Diet creator, Dr. Henry Tarnower, by his longtime companion, Jean Harris, was a slaying that awakened all sorts of emotions about the dynamics between men and women. From “Murder with Intent to Love,” a 1981 Time article by Walter Isaacson and James Wilde about the sensational trial:

Prosecutor George Bolen, 34, was cold and indignant in his summation, insisting that jealousy over Tarnower‘s affair with his lab assistant, Lynne Tryforos, 38, was the motivating factor for murder. Argued Bolen: ‘There was dual intent, to take her own life, but also an intent to do something else . . . to punish Herman Tarnower . . . to kill him and keep him from Lynne Tryforos.’ Bolen ridiculed the notion that Harris fired her .32-cal. revolver by accident. He urged the jury to examine the gun while deliberating. Said he: ‘Try pulling the trigger. It has 14 pounds of pull. Just see how difficult it would be to pull, double action, four times by accident.’ Bolen, who was thought by his superiors to be too gentle when he cross-examined Harris earlier in the trial, showed little mercy as he painted a vivid picture of what he claims happened that night. He dramatically raised his hand in the defensive stance he says Tarnower used when Harris pointed the gun at him. When the judge sustained an objection by Aurnou that Bolen‘s version went beyond the evidence presented, the taut Harris applauded until her body shook.•

In 1991, the year before her sentence was commuted, Harris sat for a jailhouse interview with Jane Pauley, who has somehow managed to not murder Garry Trudeau.