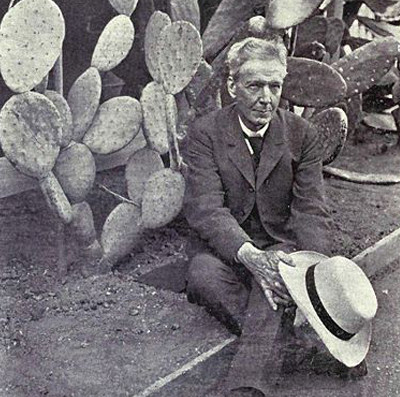

By any standards, California’s Luther Burbank was a virtuoso botanist and horticulturist, mixing, matching and creating. Among the hundreds of exotic varieties he hatched from his experimental Santa Rosa farm, greenhouse and nursery–which included plants, potatoes, fruits and flowers–was the spineless cactus. The “plant wizard,” as he was called, was a beloved public figure until months before his death in 1926 when he created a furor by simply expressing his skepticism about an afterlife. “I am an infidel,” he asserted. Burbank was mocked openly in some quarters for such heresy. Twenty years before his dramatic, if abbreviated, fall from grace, he was the subject an admiring 1906 New York Times profile. The opening:

Every summer our transatlantic steamers are burdened with great throngs of travelers beginning their pilgrimages to the shrines of departed genius. In America, too, we may visit places made illustrious by the former presence of Washington, Jefferson, Lee, Lincoln, Emerson, Poe, and other native men of genius. But, disguise it as we will, the visits are at last to cemeteries, where everything is described in the past tense.

But there is in America at this moment a man of the very greatest genius, just in the flower of his fame, a visit to whom not only emphasizes his genius and his leadership in thought and living things, but also enables one to see far into the future. There is a searchlight of truth in constant operation at Santa Rosa, Cal., and the mind and heart of Luther Burbank are the lenses through which the light is focused. Long ago I resolved to beg the privilege of standing near the searchlight and making a few observations as it illumined some of the peaks of knowledge I could never hope to scale.

Our so-called “Captains of Industry” are busy men, but many of their duties and responsibilities they may delegate to others. Luther Burbank is the busiest man in the world. I make that statement without fear of successful contradiction. His ship is alone on a vast sea of nature’s secrets. With him on the voyage of discovery are a few near relations to encourage him, a dear friend or two for protection and companionship, and several humble helpers to feed the boilers and oil the engines. But he is more alone than was Columbus, because he has no first officer, no second officer, no mate. Like Columbus, upon him alone falls the responsibility for the expedition; he alone knows why the vessel’s prow is kept always in one direction; he alone has faith that it must ultimately touch the shores of truth and reality.•