Pierre Trudeau, Justin’s dad, was the cool, cosmopolitan Prime Minister of Canada for all but ten months from 1968 to 1984, a relatively hip media sensation, one who would receive visits from John & Yoko as well as heads of state. Part of the fun of his second administration was watching him try to contain his frustration when in close proximity to American President Ronald Reagan. It wasn’t easy. From a 1982 UPI report about an interview David Frost conducted with Trudeau, who spoke of his children:

Trudeau said his political legacy to Canada would be patriation of the constitution, the National Energy Progam and his stand on the relation of rich to poor nations.

He said his greatest professional achievement was political longevity.

“It is an achievement, I think, in this turbulent society and changing world … to have managed to keep our party, with its values hopefully corresponding to the Canadian general will, a long time in office,” he said.

In the interview, Trudeau also spoke reservedly about his own talents.

“I realized that I wasn’t among the geniuses and I’d have to work harder if I wanted to perform with some degree of excellence,” Trudeau said. “I certainly realized I wasn’t very handsome nor very strong physically or strong in a health sense.”

The prime minister, 62, spoke of his ‘joy’ at becoming a father. “I want to see these young boys grow up into pre-teenagers, and then teenagers, and hopefully beyond, and give them the time they deserve,” he said.

“I realize that the longer I wait, the less they will need me, and less I will be able to give them.”•

Trudeau on responding to personal attacks in a 1972 interview.

_______________________________

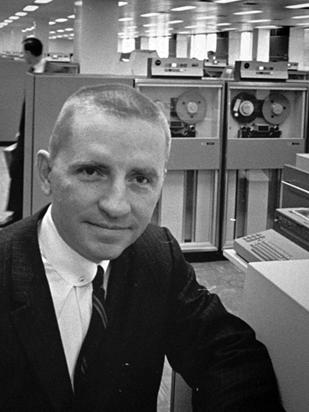

In 1969, computer-processing magnate Ross Perot had a McLuhan-ish dream: an electronic town hall in which interactive television and computer punch cards would allow the masses, rather than elected officials, to decide key American policies. In 1992, he held fast to this goal–one that was perhaps more democratic than any society could survive–when he bankrolled his own populist third-party Presidential campaign. The opening of “Perot’s Vision: Consensus By Computer,” a New York Times article from that year by the late Michael Kelly:

In 1969, computer-processing magnate Ross Perot had a McLuhan-ish dream: an electronic town hall in which interactive television and computer punch cards would allow the masses, rather than elected officials, to decide key American policies. In 1992, he held fast to this goal–one that was perhaps more democratic than any society could survive–when he bankrolled his own populist third-party Presidential campaign. The opening of “Perot’s Vision: Consensus By Computer,” a New York Times article from that year by the late Michael Kelly:

WASHINGTON, June 5— Twenty-three years ago, Ross Perot had a simple idea.

The nation was splintered by the great and painful issues of the day. There had been years of disorder and disunity, and lately, terrible riots in Los Angeles and other cities. People talked of an America in crisis. The Government seemed to many to be ineffectual and out of touch.

What this country needed, Mr. Perot thought, was a good, long talk with itself.

The information age was dawning, and Mr. Perot, then building what would become one of the world’s largest computer-processing companies, saw in its glow the answer to everything. One Hour, One Issue

Every week, Mr. Perot proposed, the television networks would broadcast an hourlong program in which one issue would be discussed. Viewers would record their opinions by marking computer cards, which they would mail to regional tabulating centers. Consensus would be reached, and the leaders would know what the people wanted.

Mr. Perot gave his idea a name that draped the old dream of pure democracy with the glossy promise of technology: “the electronic town hall.”

Today, Mr. Perot’s idea, essentially unchanged from 1969, is at the core of his ‘We the People’ drive for the Presidency, and of his theory for governing.

It forms the basis of Mr. Perot’s pitch, in which he presents himself, not as a politician running for President, but as a patriot willing to be drafted ‘as a servant of the people’ to take on the ‘dirty, thankless’ job of rescuing America from “the Establishment,” and running it.

In set speeches and interviews, the Texas billionaire describes the electronic town hall as the principal tool of governance in a Perot Presidency, and he makes grand claims: “If we ever put the people back in charge of this country and make sure they understand the issues, you’ll see the White House and Congress, like a ballet, pirouetting around the stage getting it done in unison.”

Although Mr. Perot has repeatedly said he would not try to use the electronic town hall as a direct decision-making body, he has on other occasions suggested placing a startling degree of power in the hands of the television audience.

He has proposed at least twice — in an interview with David Frost broadcast on April 24 and in a March 18 speech at the National Press Club — passing a constitutional amendment that would strip Congress of its authority to levy taxes, and place that power directly in the hands of the people, in a debate and referendum orchestrated through an electronic town hall.•

A 1992 NBC News report on the unlikely popularity of Perot’s third-party candidacy for the White House.

_______________________________

In Lauren Weiner’s 2012 New Atlantis article about Ray Bradbury, she provided a tidy description of the Space Age sage’s youthful education:

In Lauren Weiner’s 2012 New Atlantis article about Ray Bradbury, she provided a tidy description of the Space Age sage’s youthful education:

Bradbury spent his childhood goosing his imagination with the outlandish. Whenever mundane Waukegan was visited by the strange or the offbeat, young Ray was on hand. The vaudevillian magician Harry Blackstone came through the industrial port on Lake Michigan’s shore in the late 1920s. Seeing Blackstone’s show over and over again marked Bradbury deeply, as did going to carnivals and circuses, and watching Hollywood’s earliest horror offerings like Dracula and The Phantom of the Opera. He read heavily in Charles Dickens, George Bernard Shaw, Edgar Allan Poe, H. G. Wells, Arthur Conan Doyle, L. Frank Baum, and Edgar Rice Burroughs; the latter’s inspirational and romantic children’s adventure tales earned him Bradbury’s hyperbolic designation as “probably the most influential writer in the entire history of the world.”

Then there was the contagious enthusiasm of Bradbury’s bohemian, artistic aunt and his grandfather, Samuel, who ran a boardinghouse in Waukegan and instilled in Bradbury a kind of wonder at modern life. He recounted: “When I was two years old I sat on his knee and he had me tickle a crystal with a feathery needle and I heard music from thousands of miles away. I was right then and there introduced to the birth of radio.”

His family’s temporary stay in Arizona in the mid-1920s and permanent relocation to Los Angeles in the 1930s brought Bradbury to the desert places that he would later reimagine as Mars. As a high-schooler he buzzed around movie and radio stars asking for autographs, briefly considered becoming an actor, and wrote and edited science fiction “fanzines” just as tales of robots and rocket ships were gaining in popularity in wartime America. He befriended the staffs of bicoastal pulp magazines like Weird Tales,Thrilling Wonder Stories, Dime Mystery, and Captain Future by bombarding them with submissions, and, when those were rejected, with letters to the editor. This precocity was typical. Science fiction and “fantasy” — a catchall term for tales of the supernatural that have few or no fancy machines in them — drew adolescent talent like no other sector of American publishing. Isaac Asimov was in his late teens when he began writing for genre publications; Ursula K. Le Guin claimed to have sent in stories from the age of eleven.•

Groucho Marx sasses Bradbury on You Bet Your Life in 1955.