Robots have been members of the U.S. military since at least 1928, and the only question in the long term is whether our warriors will ultimately be wholly silicon or if we’ll use brain chips, drugs, exoskeleton suits and genetic manipulation to alter humans into fighting “machines.” We’ll certainly develop both, but the former’s lack of flexibility for the foreseeable future makes battlefield Transhumanism, dicey though it is from an ethical standpoint, more doable for now.

Questions abound for this new arms race: If war is relatively painless (for one side, in some cases), will it make aggression more attractive? How will these experiments in pain vaccines and teleportation eventually inform civilian life? Will humanitarian crises like Syria’s collapse be eliminated by these tools?

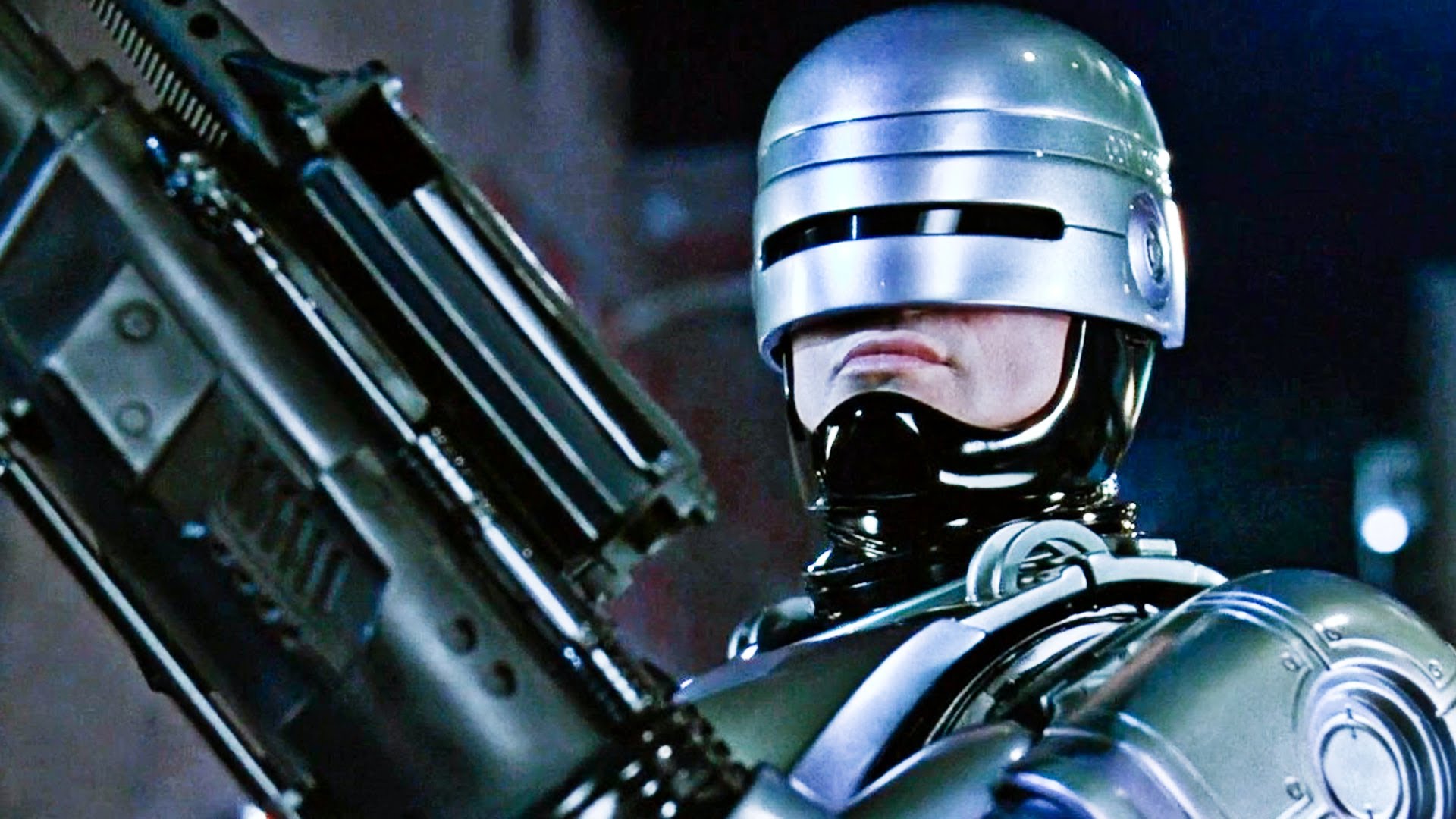

In “Engineering Humans for War,” Annie Jacobsen’s excellent Atlantic article, she looks at DARPA’s goal of creating a real-life Iron Man in numerous ways, including a super-soldier suit called TALOS (Tactical Assault Light Operator Suit), which the department expects to have operational by 2018. An excerpt:

For decades after its inception in 1958, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency—DARPA, the central research and development organization of the Department of Defense—focused on developing vast weapons systems. Starting in 1990, and owing to individuals like [Retired four-star general Paul F.] Gorman, a new focus was put on soldiers, airmen, and sailors—on transforming humans for war. The progress of those efforts, to the extent it can be assessed through public information, hints at war’s future, and raises questions about whether military technology can be stopped, or should.

Gorman sketched out an early version of the thinking in a paper he wrote for DARPA after his retirement from the Army in 1985, in which he described an “integrated-powered exoskeleton” that could transform the weakling of the battlefield into a veritable super-soldier. The “SuperTroop” exoskeleton he proposed offered protection against chemical, biological, electromagnetic, and ballistic threats, including direct fire from a .50-caliber bullet. It “incorporated audio, visual, and haptic [touch] sensors,” Gorman explained, including thermal imaging for the eyes, sound suppression for the ears, and fiber optics from the head to the fingertips. Its interior would be climate-controlled, and each soldier would have his own physiological specifications embedded on a chip within his dog tags. “When a soldier donned his ST [SuperTroop] battledress,” Gorman wrote, “he would insert one dog-tag into a slot under the chest armor, thereby loading his personal program into the battle suit’s computer,” giving the 21st-century soldier an extraordinary ability to hear, see, move, shoot, and communicate.

At the time Gorman wrote, the computing technology needed for such a device did not yet exist.•

Tags: Annie Jacobsen, Paul F. Gorman