New York City has always been about money, but it wasn’t always only about money.

In a wonderfully written T Magazine piece, Edmund White wonders why there’s nostalgia for NYC of the 1970s and early 1980s, and I think I know the answer: Despite being something of a dangerous dump in those days, when even the President told us we could drop dead, that’s the last time the city belonged to us all, people of every class, before it became wholly about real estate and Wall Street. It was livable, you could make a living, even if sometimes you had to run for your life.

It wasn’t all good. For all the NYPD harassment of minorities now, the city then was much more divided racially. And the child prostitution that was allowed to flourish in Times Square isn’t something anyone could feel nostalgic about. But it did seem, on some level, we were all in it together. Most working-class people have now been pushed to the margins of the city by real-estate prices and gentrification and globalization, and that won’t stop until they go over the edge. That’s the only edge left.

White’s opening:

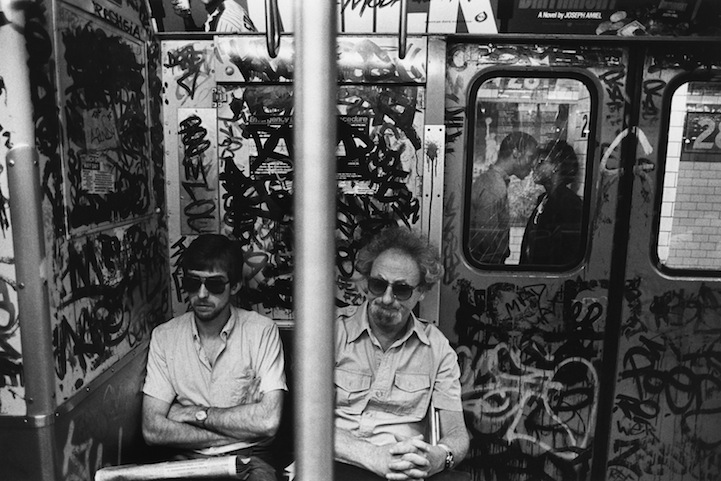

THERE IS A STRONG CURRENT of nostalgia for the late ’70s and early ’80s in New York, even among those who never lived through it — the era when the city was edgy and dangerous, when women carried Mace in their purses, when even men asked the taxi driver to wait until they’d crossed the 15 feet to the front door of their building, when a blackout plunged whole neighborhoods into frantic looting, when subway cars were covered with graffiti, when Balanchine was at the height of his powers and the New York State Theater was New York’s intellectual salon, when John Lennon was murdered by a Salinger-reading born-again, when Philip Roth was already famous, Don DeLillo had yet to become famous, and most literary insiders were betting on Harold Brodkey’s long-awaited novel, which his editor, Gordon Lish, declared would be ‘‘the one necessary American narrative work of this century.’’ (It flopped when it finally came out in 1991 as ‘‘The Runaway Soul.’’)

This was the last period in American culture when the distinction between highbrow and lowbrow still pertained, when writers and painters and theater people still wanted to be (or were willing to be) ‘‘martyrs to art.’’ This was the last moment when a novelist or poet might withdraw a book that had already been accepted for publication and continue to fiddle with it for the next two or three years. This was the last time when a New York poet was reluctant to introduce to his arty friends someone who was a Hollywood film director, for fear the movies would be considered too low-status.•

Tags: Edmund White