Impresario is what they used to call those like Steve Ross of Warner Communications, whose mania for mergers allowed him a hand in a large number of media and entertainment ventures, making him boss and handler at different times to the Rolling Stones, Pele and Dustin Hoffman. One of those businesses the erstwhile funeral-parlor entrepreneur became involved with was Qube, an interactive cable-TV project that was a harbinger if a money-loser. That enterprise and many others are covered in a brief 1977 People profile. The opening:

In our times, the courtships and marriages that make the earth tremble are no longer romantic but corporate. The most legendary (or lurid) figures are not the Casanovas today. They are the conglomerateurs, and for sheer seismic impact on the popular culture, none approaches Steven J. Ross, 50, the former slacks salesman who married into a mortuary chain business that he parlayed 17 years later into Warner Communications Inc. (WCI). In founder-chairman Ross’s multitentacled clutch are perhaps the world’s predominant record division (with artists like the Eagles, Fleetwood Mac, the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin and Joni Mitchell); one of the Big Three movie studios (its hot fall releases include Oh, God! and The Goodbye Girl); a publishing operation (the paperback version of All the President’s Men, which was also a Warner Bros, film); the Atari line of video games like Pong, which inadvertently competes with Warner’s own TV producing arm, whose credits include Roots, no less. The conglomerate is furthermore not without free-enterprising social consciousness (WCI put up $1 million and owns 25 percent of Ms. magazine) or a redeeming sense of humor (it disseminates Mad).

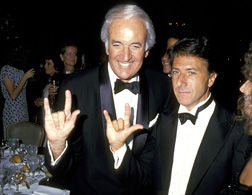

Warner’s latest venturesome effort is bringing the blue-sky of two-way cable TV down to earth in a limited experiment in Columbus, Ohio. There, subscribers are able to talk back to their TV sets (choosing the movie they want to see or kibitzing the quarterback on his third-down call). An earlier Ross vision—an estimated $4.5 million investment in Pelé by Warner’s New York Cosmos—was, arguably, responsible for soccer’s belated breakthrough in the U.S. this year after decades of spectator indifference. Steve is obviously in a high-rolling business—Warners’ estimated annual gross is approaching a billion—and so the boss is taking his. Financial writer Dan Dorfman pegs Ross’s personal ’77 earnings at up to $5 million. That counts executive bonuses but not corporate indulgences. On a recent official trip to Europe in the Warner jet, Steve brought along his own barber for the ride.

En route to that altitude back in the days of his in-laws’ funeral parlor operation, Ross expanded into auto rentals (because he observed that their limos were unprofitably idle at night) and then into Kinney parking lots. “The funeral business is a great training ground because it teaches you service,” he notes, though adding: “It takes as much time to talk a small deal as a big deal.” So, come the ’70s, Ross dealt away the mortuary for the more glamorous show world. Alas, too, he separated from his wife. •

Tags: Steve Ross