Marshall McLuhan was right, for the most part.

The Canadian theorist saw Frankenstein awakening from the operating table before others did, so the messenger was often mistaken for the monster. But he was neither Dr. Victor nor his charged charge, just an observer with a keen eye, one who could recognize patterns and realized humans might not be alone forever in that talent. Excerpts follow from two 1960s pieces that explore his ideas. The first is from artist-writer Richard Kostelanetz‘s 1967 New York Times article “Understanding McLuhan (In Part)” and the other from John Brooks’ 1968 New Yorker piece “Xerox Xerox Xerox Xerox.”

____________________________

Kostelanetz’s opening:

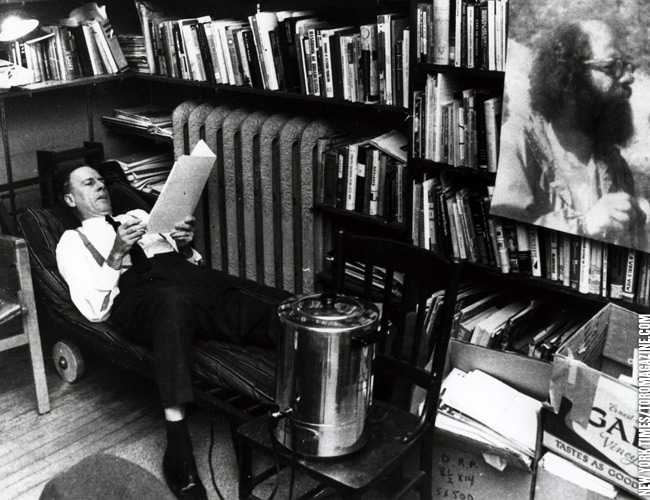

Marshall McLuhan, one of the most acclaimed, most controversial and certainly most talked-about of contemporary intellectuals, displays little of the stuff of which prophets are made. Tall, thin, middle-aged and graying, he has a face of such meager individual character that it is difficult to remember exactly what he looks like; different photographs of him rarely seem to capture the same man.

By trade, he is a professor of English at St. Michael’s College, the Roman Catholic unit of the University of Toronto. Except for a seminar called “Communication,” the courses he teaches are the standard fare of Mod. Lit. and Crit., and around the university he has hardly been a celebrity. One young woman now in Toronto publishing remembers that a decade ago, “McLuhan was a bit of a campus joke.” Even now, only a few of his graduate students seem familiar with his studies of the impact of communications media on civilization those famous books that have excited so many outside Toronto.

McLuhan’s two major works The Gutenberg Galaxy (1962) and Understanding Media (1964) have won an astonishing variety of admirers. General Electric, I.B.M. and Bell Telephone have all had him address their top executives, so have the publishers of America’s largest magazines. The composer John Cage made a pilgrimage to Toronto especially to pay homage to McLuhan and the critic Susan Sontag has praised his “grasp on the texture of contemporary reality.”

He has a number of eminent and vehement detractors, too. The critic Dwight Macdonald calls McLuhan’s books “impure nonsense, nonsense adulterated by sense.” Leslie Fiedler wrote in Partisan Review “Marshall McLuhan. . .continually risks sounding like the body-fluids man in Doctor Strangelove.

Still the McLuhan movement rolls on.”•

____________________________

From Brooks:

In the opinion of some commentators, what has happened so far is only the first phase of a kind o revolution in graphics. “Xerography is bringing a reign of terror into the world of publishing, because it

means that every reader can become both author and publisher,” the Canadian sage Marshall McLuhan wrote in the spring, 1966, issue of the American Scholar. “Authorship and readership alike can become production-oriented under xerography.… Xerography is electricity invading the world of typography, and it means a total revolution in this old sphere.” Even allowing for McLuhan’s erratic ebullience (“I change my opinions daily,” he once confessed), he seems to have got his teeth into something here. Various magazine articles have predicted nothing less than the disappearance of the book as it now exists, and pictured the library of the future as a sort of monster computer capable of storing and retrieving the contents of books electronically and xerographically. The “books” in such a library would be tiny chips of computer film — “editions of one.” Everyone agrees that such a library is still some time away. (But not so far away as to preclude a wary reaction from forehanded publishers. Beginning late in 1966, the long-familiar “all rights reserved” rigmarole on the copyright page of all books published by Harcourt, Brace & World was altered to read, a bit spookily, “All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system …” Other publishers quickly followed the example.) One of the nearest approaches to it in the late sixties was the Xerox subsidiary University Microfilms, which could, and did, enlarge its microfilms of out-of-print books and print them as attractive and highly legible paperback volumes, at a cost to the customer of four cents a page; in cases where the book was covered by copyright, the firm paid a royalty to the author on each copy produced. But the time when almost anyone can make his own copy of a published book at lower than the market price is not some years away; it is now. All that the amateur publisher needs is access to a Xerox machine and a small offset printing press. One of the lesser but still important attributes of xerography is its ability to make master copies for use on offset presses, and make them much more cheaply and quickly than was previously possible. According to Irwin Karp, counsel to the Authors League of America, an edition of fifty copies of any printed book could in 1967 be handsomely “published” (minus the binding) by this combination of technologies in a matter of minutes at a cost of about eight-tenths of a cent per page, and less than that if the edition was larger. A teacher wishing to distribute to a class of fifty students the contents of a sixty-four-page book of poetry selling for three dollars and seventy-five cents could do so, if he were disposed to ignore the copyright laws, at a cost of slightly over fifty cents per copy.The danger in the new technology, authors and publishers have contended, is that in doing away with the book it may do away with them, and thus with writing itself. Herbert S. Bailey, Jr., director of Princeton University Press, wrote in the Saturday Review of a scholar friend of his who has cancelled all his subscriptions to scholarly journals; instead, he now scans their tables of contents at his public library and makes copies of the articles that interest him. Bailey commented, “If all scholars followed [this] practice, there would be no scholarly journals.” Beginning in the middle sixties, Congress has been considering a revision of the copyright laws — the first since 1909. At the hearings, a committee representing the National Education Association and a clutch of other education groups argued firmly and persuasively that if education is to keep up with our national growth, the present copyright law and the fair-use doctrine should be liberalized for scholastic purposes. The authors and publishers, not surprisingly, opposed such liberalization, insisting that any extension of existing rights would tend to deprive them of their livelihoods to some degree now, and to a far greater degree in the uncharted xerographic future. A bill that was approved in 1967 by the House Judiciary Committee seemed to represent a victory for them, since it explicitly set forth the fair-use doctrine and contained no educational-copying exemption. But the final outcome of the struggle was still uncertain late in 1968. McLuhan, for one, was convinced that all efforts to preserve the old forms of author protection represent backward thinking and are doomed to failure (or, anyway, he was convinced the day he wrote his American Scholar article). “There is no possible protection from technology except by technology,” he wrote. “When you create a new environment with one phase of technology, you have to create an anti-environment with the next.” But authors are seldom good at technology, and probably do not flourish in anti-environments.•