John Sculley is, similar to the late Steve Jobs, a creative person (Architecture at Brown, Art as RISD) with a mind for business, so it’s sad he’s usually depicted so reductively in the popular narrative of Apple. Even Steve Wozniak has pushed back at this crude portrait. The Newton was a great idea, and things might have been different had it not been roughly a decade ahead of the technology.

Two passages follow from a 1993 People article by Craig Horowitz at the end of Sculley’s run atop the company.

___________________________

If Sculley is running on pure adrenaline these days, who can blame him? At a time when most personal-computer makers—including the behemoth IBM—are struggling for survival, Apple posted record revenues last year (more than $7 billion). The Powerbook, its notebook computer introduced in 1992, quickly became the best-selling computer on the market and a must-have accessory for the trendy. But for Sculley, selling computers is only the beginning. A Renaissance man who once had his sights set on a career in architecture and design, Sculley wants to change the world. Or at least America.

“Our resources are no longer coal and iron ore and things that come out of the ground,” he says in his sparsely furnished office at Apple headquarters in Silicon Valley. “The strategic resources are things that come out of people’s minds.” Sculley has campaigned vigorously for fundamental changes in education, job training and the economy to meet the high-tech future. He is also fighting for the construction of a technology infrastructure—a nationwide “data superhighway”—that would transmit vast quantities of information quickly and help create jobs.

It is this vision of the future that transformed Sculley, a lifelong Republican, into an avid Clinton supporter. George Bush “is a very nice person, but he obviously had no interest in anything we [in the high-tech industry] were talking about,” says Sculley. “Remember, this was the President who was amazed by the scanner in a supermarket.” Sculley, who had met the Clintons while Bill was still a Governor, helped mobilize the business community for the Democratic ticket and has become a valued adviser to both Bill and Hillary. “John was instrumental in the development of the President’s overall economic plan,” says White House Chief of Staff Thomas McLarty. The Clintons, Sculley says, “are the kind of people I’m attracted to. They’re builders.”

___________________________

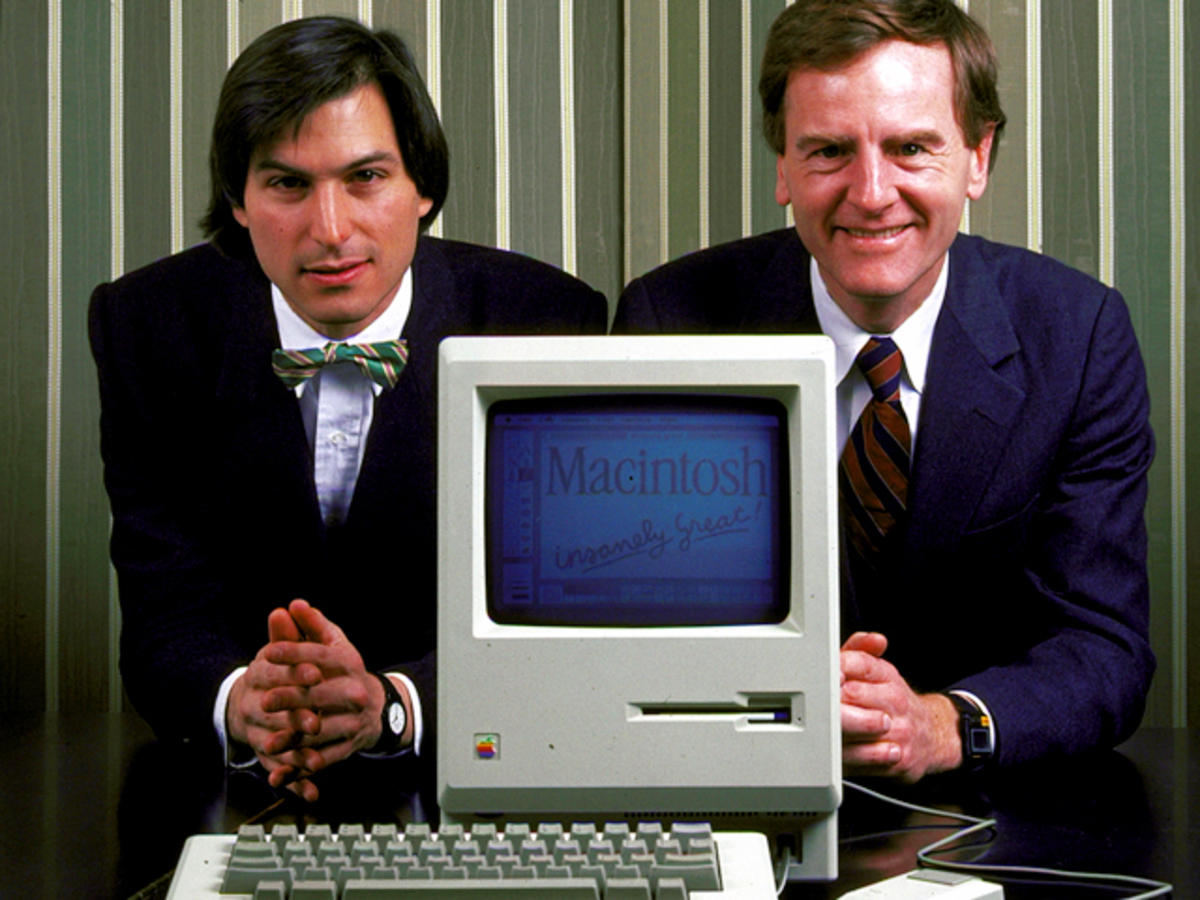

By 1982, Sculley was one of three hand-picked contenders to replace Kendall as chairman of PepsiCo when he retired. It was then that Sculley was unexpectedly offered the top spot at Apple. He knew little about computers, but was attractive for his management skills. Though Apple was only five years old—having moved al warp speed from a company located in the garage of its founders, Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs, to the FORTUNE 500—the opportunity captured Sculley’s imagination. So did the now famous pitch made by Jobs, then 28, a vegetarian and a college dropout. “Do you want to spend the rest of your life selling sugar water?” Jobs asked Sculley. “Or do you want a chance to change the world?”

Choosing the latter required an adjustment of epic proportions for Sculley. who had to go from pinstripes to corduroy and from formal meetings in the august PepsiCo boardroom to brainstorming in Apple’s funky cubicles. Perhaps most significant, he went from being a respected leader in his industry to an object of suspicion that he was just another empty suit. Sculley quickly proved otherwise when, less than two years into his tenure at Apple, the bottom fell out of the computer market. Sculley had to make tough decisions—decisions Steve Jobs couldn’t live with. “Everyone says I took his company away from him,” Sculley says, “but I told him he could have it back. I didn’t like the direction it was going. It was ultimately the board of directors who made the decision.” Jobs, who quit and started a computer company called Next, refuses to comment.

To get Apple back on track, Sculley, who is known for such openhanded policies as on-site childcare, profit sharing and employee sabbaticals, cut staff, closed factories and reorganized the company. When a second crisis occurred in 1990, he reduced his own $2.2 million salary by a third and look over the reins as technical chief. In that role, he has now bet the future of the company on a new group of products called the Newton, scheduled for introduction later this year. The small, hand-held devices perform a wide variety of office functions—as typewriters, calculators, calendars, faxes, modems, telephones and radios. “If it works out well, it will be great.” he says. “If it doesn’t work out, I guess I’ll be looking for a new job.” With Sculley’s history, no one is betting against him.•

Tags: Craig Horowitz, John Sculley, Steve Jobs